Words by Andrew Parks

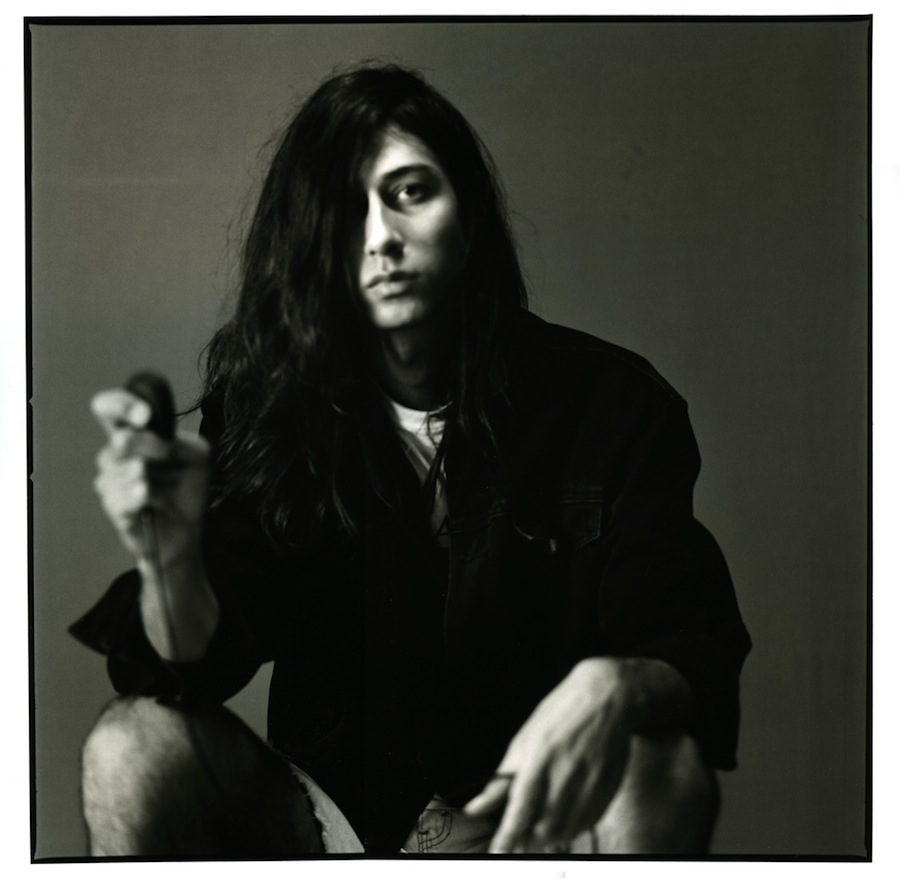

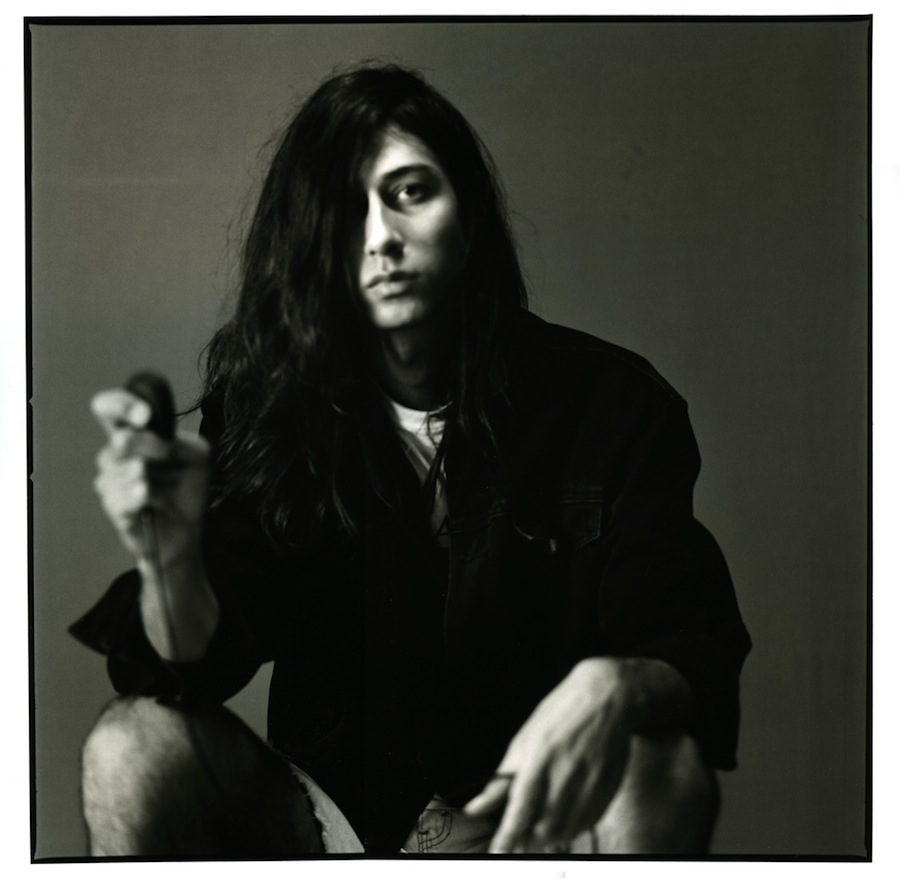

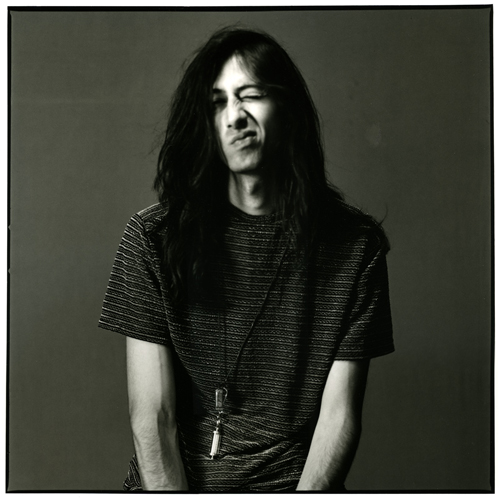

Adam Bainbridge is fully aware of the love or hate proposition his music presents. In fact, he’s witnessed it firsthand.

“Just this past weekend, someone misunderstood something I said in French,” explains the Kindness frontman. “They thought I was being facetious about the EastEnders cover (“Anyone Can Fall in Love”) or something.

He continues, speaking softly and steadily over the sound of coffee brewers and copy machines in a Paris cafe, “There’s this thing where if you have even a grain of cynicism in you, you’re always looking for a way to express it in the face of something that’s ridiculous. You’re waiting for the Achilles’ hell so you can say, ‘I knew it! He’s an ironic scumbag! Fuck that guy!'”

We didn’t quite have the same reaction to Kindness’ first proper LP, World, You Need a Change of Mind (available now through Terrible Records). If anything, we didn’t know what to make of Bainbridge’s solo work at first; after all, it’s not every day that a dude who looks like an model happens to sample Trouble Funk wholesale and cover both the Replacements (“Swingin’ Party”) and an obscure, defiantly cheesy theme song (Anita Dobson’s “Anyone Can Fall in Love,” taken from the BBC soap opera EastEnders).

We get it now though. As you’re about to read in a lengthy self-titled exclusive, Bainbridge is out to reclaim the open-minded omnivorism that once characterized such iconic clubs as the Paradise Garage and David Mancuso’s Loft. Folks in Philly and New York can hear and see what we mean when Bainbridge plays a couple rare live dates tonight at (Le) Poisson Rouge and tomorrow at Making Time’s twelfth anniversary party…

Let’s start by talking about your live show. I was surprised by how tight you were at South by Southwest, considering it was one of your first performances. Where did you find your band? Are they people who played on your record?

No. The guys on the record were unavailable for live shows, so we tried to find people who were based in London, although in actuality, the record sounds quite American. The playing is quite straightforward, but what informs it is quite jazzy and old-school.

Well it sounds very ’80s in a way that isn’t as trendy as other attempts at recreating that era. The first time I played it in the office people thought one of the songs was an old New Jack Swing record.

Right. For a minute there, I thought, ‘Oh shit, I’m going to have to use American musicians.’ As it happened, the network of musicians in London really helped me. There was a lot of, ‘What about this guy? He hasn’t gotten to express his crazy jazz-funk upbringing for a while. I bet we could coax it out of him.’ I was quite surprised; it took two or three rehearsals of every song to bring them up to speed. And it could only improve after that.

How many rehearsals did you have before South by Southwest?

Two maybe?

So you’re basically working with session musicians.

I don’t know; it doesn’t feel that way because they genuinely seem to like the record, and they asked to play in the band. It’s maybe 50-percent musicality and memory, and the other 50-percent is pure enjoyment and motivation. I try to make sure everyone has a great time. We played two shows this past weekend, and it was one of those things where you look around and think, ‘Holy shit, probably half of the audience is hating this right now, but isn’t it more important that the band’s actually having a great time?’ That way, you can really hate on something, but you can’t deny that it’s genuine. It’s impossible to fake real enthusiasm, I think.

Have a lot of shows felt hit or miss like that?

It’s felt like if people get it, they really get it, and if they don’t get it, they also really don’t get it. And that’s totally reasonable. I could see why certain sounds would rub people the wrong way. There’s a lot of people who can’t understand 100-percent joyful silliness and a bunch of music fans playing together. But you know, if I saw a band without knowing much about them, I might imagine on the first reading that it’s all part of some evil master plan. Because so much of what comes out in modern music is on a certain level. People know how to be Machiavellian in music production, so they just do it. There’s probably someone in a cool-hunting lab somewhere saying, ‘Why didn’t anyone think of that? To combine all of the most unfashionable elements of music and get on stage?’

Well I wasn’t looking to hate your set so much as not expecting to take much away from it. The way the record sounds, I figured it would be more of a studio thing, and your live set would go more of a laptop-based route.

That’s something you almost have to ignore when making a record–that idea of, ‘How are we going to recreate this live?’ If you think that way, you’re kinda fucked.

I remember speaking to Chris [Taylor] and Ethan [Silverman] from Terrible Records earlier in the process, and Chris saying, “Dear god, there’s enough laptop guys in the universe now. Don’t be another one.” Now I will gladly see one guy and his laptop if it blows my mind. In fact, I can think of some people who do. There’s a need for backing tracks sometimes, especially when what you’re doing is truly DIY, when you’re writing everything in your bedroom and don’t have the budget or peer network to get great musicians together.

One of your earliest features was in the Guardian</em> a few years ago, and they actually did lump you in with the Toro Y Moi’s and Washed Out’s of the world.

Did they say that? I don’t even know where that weird chillwave association comes.

Well I’m not saying you sound that way. It’s just that sometimes it seems like people can find no other way of classifying solo, sample-based artists.

It’s actually a tag that’s stuck around the past few months. And it confuses me. I understand the genre fusion of those guys. Maybe that’s it–how Washed Out would take an Italo-disco track, slow it down, and sing over the top of it. That tendency is labeled as a particular musical genre but it’s quite meaningless. It makes no sense to me considering how hi-fi some of the recordings are. If I turned around and told [producer] Philippe [Zdar] people think the album is lo-fi, he’d probably have a fit and start sending letter bombs. It’s strange. [Laughs]

Well writers tend to put everything into a tidy box with a little bow on top. And since there aren’t a lot of people making what you’re making, people aren’t sure how to describe it beyond saying, ‘Well, there’s a little bit of funk, and some disco, and some R&B.’

It kinda makes you think if DJ Shadow put Endtroducing… out right now, people would be like ‘it’s a great chillwave album.’

God, I hope not.

Yeah, and they’d be like, ‘Hey, have you heard that Aphex Twin–Selected Ambient Works? It’s such a great chillwave album.’ It’s like, ‘Come on guys, be a little more creative.’

“Back then, there was this simple idea of ‘I’ll dance to something if it’s good, even if it’s only the first time I heard it and it’s really fucking weird'”

I’m curious how you got into the music that clearly influenced this record. A lot of it sounds like the records you’d hear at classic clubs like the [Paradise] Garage in the late ’70s and early ’80s. Did you discover a lot of music through reading about that era, and listening to old mixes?

Yeah, I went through a serious research phase where I couldn’t get enough information about that whole moment in time. It really fascinated me, right down to something as simple as the positive energy of this music. I’d been checking out track from the Garage on YouTube, and it was the only time in my life where 100-percent of the YouTube comments were positive. That in and of itself seemed like a miraculous occurrence. It made me think, ‘Who the hell are these people who don’t have a bad word to say about each other or the music itself?’

But yeah, I watched Maestro, the Larry Levan documentary; I read the Bill Brewster book (Last Night a DJ Saved My Life); I read the Tim Lawrence book (Love Saves the Day) about the New York scene. And then I read Arthur Russell’s biography, Chic: the Politics of Disco, then another Chic biography, and the new Nile Rodgers book (Le Freak). All of it started to float together. It really says something about a moment in time where people were open-minded and there was a generosity of spirit where you could collaborate with anyone and people would receive it with open arms.

For me, the Garage is the be-all, end-all of nightclubs. I can’t imagine being happier than in a space with an incredibly powerful sound system playing the B-52s followed by Fonda Rae followed by something weird, European and rocky. It’s inconceivable now–that kind of playlist would be looked at as deliberately eclectic. The audience would need to be super educated to follow the flow from one track to another. But back then, there was this simple idea of ‘I’ll dance to something if it’s good, even if it’s only the first time I heard it and it’s really fucking weird.’

Which is very rare these days; as plentiful as music is now, people still want to hear what they know when they go out to clubs.

I wonder about the sound [of the Garage] itself. Having read a lot about it, the power and attention to detail in that system probably meant that any well-recorded record would sound fantastic on it. There’s an inherent motivation to dance then, whether you understand what you’re hearing or not. We lack that. It’s weird; we’re a generation that’s taught itself to be very blind to genres and comfortable with any tempo, and yet even the great music nerd DJs end up sticking around a kick drum and 120 BPMs for two hours of the night. Maybe it’s because the audience dictates that in turn.

Shifting back to the start of this project, when did you live in Philly?

2007, I think. It’s crazy; I’m really looking forward to going back there.

How long did you live there? Just long enough to finish your first record (Live in Philly)?

I was there for a month. The first two weeks was just me trying to find people to work with, and exploring the city. The residency they offered me was meant to be rooted in Philadelphia as it is for young artists–why it was a good place to make art at that moment in time. It was genuinely inspiring, riding out to stores in the middle of nowhere, going to great gallery shows. It was a very welcoming city; the experience definitely stuck with me more than the typical rush and buzz of a visit to L.A. or New York. Philadelphia was rich in a different way.

“‘Oh, it’s that weird English guy again, riding the bicycle that’s too small and trying to tell me about a TLC covers tape he found at the thrift store'”

It’s a great city to visit. One of the drawbacks to it, depending on who you ask, is that it’s so cheap to live there, you don’t have to push your art or put yourself out there too much.

That’s the old Berlin scenario in Europe–it gives you the opportunity to do what you want, but the infinite stretch of time ahead of you sometimes sucks you into this vortex of open bars, bad gallery openings, eating falafel, and never getting around to doing what you came there for in the first place. My experience [in Philly] may have been different because it was the first couple months of that art space. Everyone was hyper and ready to prove themselves. It was a fantastic energy to leapfrog on. It was really the beginnings of this project–finding this open-minded generosity in my generation of people, where they’re willing to go out on a limb and make stuff with one another.

If you were faced with nothing but the cynicism that’s omnipresent in London, you’d just give up. You’d think, ‘I’m an idiot to even try this. I doubt there’ll ever be any real support for this.’ But then I went to Philadelphia and it was like, ‘Oh, it’s that weird English guy again, riding the bicycle that’s too small and trying to tell me about a TLC covers tape he found at the thrift store. Let’s roll with it.’

So to oversimplify things, London kinda bummed you out for a little while there, and Philly recharged your creative batteries?

Something like that. There was a choice to not make that record in London with British people. It didn’t seem like a good, creative environment.

What was the deal with your Philly residency? Was that a grant you applied for, and they gave you a certain amount of time to work with local musicians?

It was pretty straightforward. A friend of mine, who I’d met in Berlin–the same person who saw me struggling with GarageBand and gave me my first copy of Ableton–sent me an email and said he’d set up a studio in this warehouse. And since I hadn’t had the time and space to focus on music then, he asked me to stay there for a month with a p.a., four-track, guitar and a bunch of cables. That’s what started it for me. It was a pretty amazing project because it got a lot of people from very different backgrounds really pumped and ready to work. It was also an incredible introduction to another part of the Northeast and what’s great about America.

What about it appealed to you specifically? Was it the scrappiness of Philadelphia?

Philadelphia was reactionary in a way, where kids would throw themselves wholeheartedly into the art they make, and they’d go to a noise show and a poetry reading and a mixed genre R&B/Baltimore party because it’s great to dance to. That really inspired me–that anything goes attitude, like, ‘There’s a man coming down the stairs in a wedding dress. He’s about to play the accordion and give a poetry reading. Then the Bavarian Society is going to cook for us in the back garden.’ It was just ridiculous. And I embrace ridiculousness, people who aren’t afraid of being perceived as odd or vaguely unpleasant sometimes.

Were you viewed as the odd man out in your hometown?

Potentially, but I left early enough where it didn’t really matter. I also dropped out in the second year of university –after I’d dropped out once already–because I was a little surprised that the core of individuals I met growing up already had that anything goes mentality. We were quite supportive of each other’s weirdness and extravagance in this small town, so I thought a big university in London would be that, only exponentially crazier. If anything, it was more conservative than the small provisional town I’m from. People in their early 20s weren’t willing to go out on a limb unless it was very specific, like, ‘I only go to noise shows’ or ‘I only listen to hardcore music.’ And if you’re not willing to accept that gang mentality, you’re not going to be accepted in that segment of youth culture. The underground in London still has a streak of elitism. It’s meant to kick back at the mainstream, but in the end, it just makes it hard to get anything done. I kept trying to simply engage people with that very tight-knit, intelligent underground, and after about the sixtieth rejection, I thought, ‘Fuck this, I’m just going to do pop music.’

That’s how things happened organically, although I did tell people I needed six months to write new songs after I signed my deal. I wanted to have that concerted period of work because I felt like there’d never be a focused period of work again once it all begins. It’s always going to be a schizophrenic juggling act.

When people say I went away for three years, I think this will be the first time 99.9999-percent of people have heard of this project. Seeing that my sound isn’t rooted in 2011, 2012 or 2013, it doesn’t really matter, either. The only thing that does matter, I remember Philippe saying, is that we get the record out there in case someone else sampled Trouble Funk first.

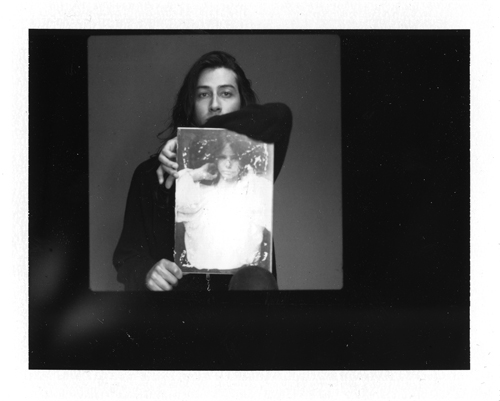

The cover songs on the record are very all over the map. Did you do that so that they’d be representative of how diverse your tastes are, and so that you could make those songs your own? Like I don’t think anyone listening to the Replacements cover is going to immediately make that connection.

I’m not even sure Replacements fans who only know their singles would recognize that song as the Replacements. It’s much more ballad-y than what they’re known for. I think that’s what attracted me to it–this heartfelt, beautiful ballad was just fun to record. The same goes for “Anyone Can Fall in Love”–it was a question of, ‘Will this be fun to do?’ A lot of the songs ended up on the album after I blindly played them for Philippe. I let him help pick the 15 songs we should work on, whether they were covers or not.

He seems like the brutally honest type, too.

I remember playing him an alternate mix of something that wasn’t working and he said [mimicking a French accent], ‘Okay, okay, never play that for me again.’

Check out the next issue of self-titled in late June for a special Kindness feature about Scrabble and your chance to play Adam online and win a special vinyl prize pack from Terrible Records.