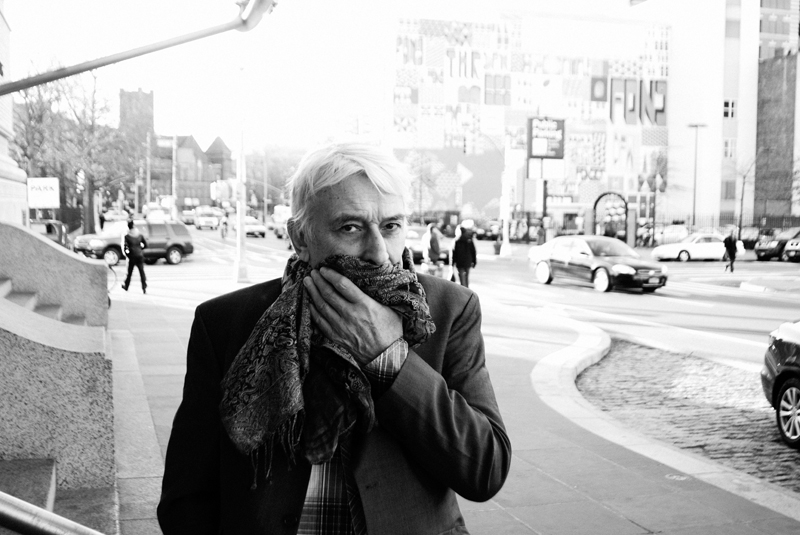

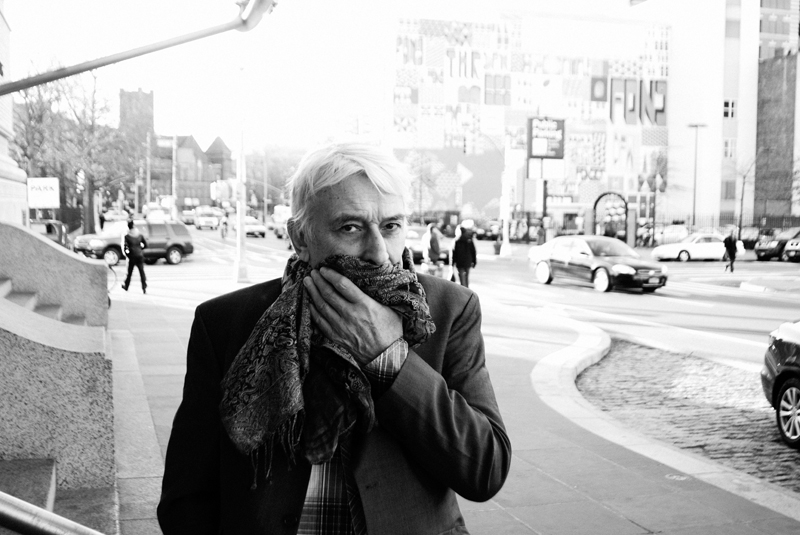

Interview by Cassie Marketos

The following transcript is taken from our recent conversation with John Cale. It was captured at his hotel room as he rehearsed for a week of wildly ambitious shows at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. (We reviewed Cale’s Nico tribute–featuring appearances by Sharon Van Etten, Peaches, Kim Gordon and more–here.) Our interview was edited into a series of revealing pull quotes for our winter issue, and is presented in full below for those of you who like reading about the following: Leonard Cohen, John Cage, the early days of the Velvet Underground, La Monte Young, drones, the Beatles, showbiz, how to piss off concert promoters…

self-titled: I mean this sincerely; are you ever bored?

I change up. I go out and look around for books or I go to the gym or read; I just do different things. I call up somebody else I haven’t heard from in a long time.

Actively seeking inspiration? More organic?

You never know where inspiration’s going to come from. It’s a good way of trolling.

When do you realize you’ve come across something good?

If there’s some unusual combination of things happening. You know, you talk to people about various things and you find the way two disparate conversations have a connecting line. You put two completely alien things together. I mean, that works for music–take two different styles and put them together, and you get a third one.

How important it is to break the rules?

The rules are whatever situation you’re in at the moment. So if you want to change that or if you want to do something different–which is generally my tendency–you just try to find different ways of nudging it. You don’t have to throw a spanner [Ed. note: Welsh slang for hammer] in the works. You can do it gently. Play something very, very slowly. Just change the speed a song is in. There’s all sorts of ways of doing it.

You’re well known for covering “Hallelujah” at a tempo that defined future versions of it–the pace people identify it with.

Leonard’s tempo was much slower than mine. There were 15 verses, so it took a really long time to sit through a performance with Leonard. He was always very stately with it. I took it at the speed I could make sense of the words, because really that’s what makes it in the end. Can you grab people’s attention and hold it?

How did you decide you wanted to cover his song? Was it just for the I’m Your Fan compilation?

I remember hearing it when I went to see a Dylan concert at The Beacon, and he was on in the first half and sang the song, and I thought, ‘That’s really a catchy chorus.’ I really liked it. Then I forgot about it until the people at Les Inrockuptibles called up and said they were doing an album of his stuff, and did I want to sing one of his songs? I mean, I knew all the other songs. But I had to trim down the 15 verses on this one to verses I identified with, because a lot of them are pretty religious, and I don’t have much credibility talking about religion.

It’s interesting to hear you talk about lyrics, because I think of you as a composer, first and foremost. It was your education and your roots. What drew you to that?

Yeah, oh yeah. In those days if you were a viola player, you didn’t have much to work with. They always had great violin concertos to practice, or aim for, but violists didn’t. There are maybe three or four concertos, and the viola is really sort of melancholy, so amplifying it and getting it out from that corner that it was in was a really good way of doing it.

How did you pick up a viola in the first place?

The local grammar school; the local authority buys them a bunch of instruments so they can then have the school orchestra. When I came around to look for something, all of them were gone except for the viola.

Ah, so it was pure chance? And you took to it?

Yeah! Well, I dunno if I liked it. I think I liked the fact that it was different. I mean, it seemed like I was ready for a crusade, so I decided to just go with it. The only thing you could do with those things as take all the stuff for violin and play it on viola-you had a couple of concertos but they were too difficult for you if you were just starting. So it was something that built up over time.

Your expertise or your interest in pushing the boundaries of what it could do?

Yeah! Because if you had to play an instrument because it was literally the only thing available to you, you could really get tired of it. Everybody’s going to gravitate toward the violin anyway, and you know there are some beautiful things a violin can play, but it doesn’t amplify as well as the viola does.

Is that what caused you to gravitate toward other instruments and experimentation, like screaming at plants during live performances?

I was a real big fan of La Monte Young because his pieces were really far out; they were very, very advanced. Compositions that were instructions for people to do certain things, but they were about something totally different. In the end, the instructions for the performance–”draw a straight line and follow it”–was a way of proving whether space was finite or not. You draw a straight line you come back to where you start, the means space is finite, and if you don’t, that means its infinite. You know, it’s a rubric. And a lot of people have tried to perform it, and have performed it, but the real point of the piece is something else entirely from being a musical performance. It’s a theatrical performance. And screaming in front of a plant until it died was my contribution to that genre of performing.

It’s a fine line between music and theater.

It’s become a lot clearer. When La Monte wrote these early pieces, I think everybody was kind of baffled by them. I don’t think John Cage would have paid tribute to La Monte the way he did if he weren’t something special. He wrote very slow pieces.

What made you eventually gravitate toward pop?

Well, by the time I got to it, I was late to the party. I had to cover a lot of ground really quickly. The best way of doing that was to write a bunch of songs and get that genre together. To go from the avant garde into pop music, well, it’s a bit of a step. From my point of view, I just wanted to write songs that extended what I knew about classical music. But certainly Vintage Violence didn’t do that. By the time I started writing songs I was 23, or whatever, and if it wasn’t for the Beatles explosion I wouldn’t have got to them. But that middle year in New York in ’64, when the Beatles were around, that was really inspirational.

Even if you were inspired by your surroundings, I do feel you made the sound your own.

When you’re working on such rarified things as the drone and an intonation system, and outside in the big wide world, you’ve got these really attractive melodies and songs going on–it’s in the air and everybody’s excited about the Beatles–it’s like you can’t ignore it. Especially if you sort of missed out on it in your teenage years. I mean, I was trying to form a jazz band in Wales as a teenager and got nowhere. So all of a sudden I had this opportunity in New York to try anything. So, it was pretty easy. I mean, everybody was excited about what the Beatles were doing, and after a year and a half of working with drones, it’s great to have a melody to latch onto. And not just any melodies, but the Beatles really had some accessibility to them, some thinking going on, especially in John Lennon Songs.

Which ones?

“She Said She Said.” You know, as soon as Dylan sort of launched into “Subterranean [Homesick Blues],” suddenly the Beatles paid attention, and their looks changed. So, you know, we just jumped on the bandwagon and said, ‘Hey! We can write lyrics, too!’ And we’re going to write about things that are really not things you’re familiar with really.

How did you feel afterward?

I thought we made a mark! I mean, that first album had a lot of ideas in it. The second one…a little fewer. They were kind of–we put a marker down.

Later on, in the ’70s, you released a trio of albums with Island that were widely viewed as dark and paranoid, largely consumed with death. Where did that come from? What fueled it?

Well, it’s really how much of thought processes you want to put into songs. Some, you don’t want to put much at all–you want to talk about one or two things. But if those one or two things are really a source of great pain for people, and fewer people want to write about that, but we sort of went for those things because they were interesting. They were motivational for human behavior.

You’ve often referenced John Cage’s idea that there is no “real silence” and how important noise is for your creative process.

It was totally against the European ideal when it became ‘hush, listen to the music’–can’t talk in concerts, that sort of thing. Well, that was the fear, anyway. But John Cage’s point was that you could try as much as you wanted to have perfect conditions to listening to music, but you’re never going to find it because there’s always noise going on.

Do you embrace that? Are you conscious of it?

No. I don’t really think about that, anymore. I have my little studio, I like going in there, and I wrap myself in whatever sounds are in there, and I come out with a song.

Does the way people listen to music affect the way you make it?

I suppose so. It seems to me the there is a ton more music all of a sudden because of the Web than there was before when it was just radio.

Does that make you less enthusiastic about recording new stuff?

I think it’s fascinating that you can troll for more stuff, of what you want, or troll for stuff you don’t know anything about. And there’s so much of it out there. Not just stuff in your own language, but stuff in other people’s languages.

What do you see yourself doing next?

I don’t really think about it. Sometimes it occurs, but more often than not, things just happen. I don’t write songs on the piano or on the guitar anymore. I mean, I write them in the studio using the studio as a hands on way to do it. And real noises, and stuff like that. So I think I tend to start things more with a groove than anything else. You find something attractive that you make that’s a rhythmic base, and then you layer it. Somewhere along the line an idea will pop up in your head of a phrase that will work, and from that phrase you extrapolate what the subject matter you’re going to sing about is.

What about when you collaborate?

You let people finish off what you start, or you finish off what someone else has started. It’s a process of suggestibility. You know, you suggest ‘can we try this over here?’ and bounce ideas off of each other.

Is it weird for you to listen back on old recordings you’ve made, like with The Velvet Underground?

The main thing is, you just notice more and more that the recordings…it’s like listening to something through gauze. The older they get, the more fuzzy they sound to you. And if you’re working in a digital medium now, you have a lot of clarity. You also have a lot more control, but what I mean is those records don’t seem to have the bite that they used to.

Yeah, recording back then did present some limitations. But maybe it was inspiring to try to overcome them. Do you ever get nostalgic for the old ways?

No, not at all! Not the way we recorded the banana album, especially. You can move faster through the process these days. If you want to finish the song, you can really work on it, and if you’re not satisfied or you’re not sure about something, you can change your mind, fix it in about 30 minutes, and have it back up in a different format. It’s much more malleable and functional.

How does that compare to how you recorded the banana album?

Oh, you know. The studio was being torn up! There were no floorboards. We had to be really careful how we walked across it, because the floorboards were up. We just put the mics anywhere they’d stand up. It’s a Raggedy Anne situation.

You still play those songs. Is it exciting to hear them on new terms?

No, that’s not what excites me! The new material excites me. When we made Nookie Wood we thought carefully about how far we could go in dressing up the song, and how far we could go with that in live performance. We were trying to think about it in the simplest terms possible. You know, this was going to be very simple to perform live. Because, you know, the exciting thing about live performances is hearing what you had on a record in a more dynamic and forceful way.

A chance to continue to innovate?

Yeah! Live performances are it. That’s when you have other people. When you’re up on a stage, you’re not listening to what you’re playing. You’re listening to the audience. You’re listening to the interaction between the music and the audience. That’s what I’m always aware of, that’s why I like live performance more than just sitting in a studio writing.

How can you tell what a song is resonating?

Oh, I dunno. There was one really good example, we went to Portland, and we played. There was a song called “Cry,” and I was convinced we should try it and that people would really go for it, but I couldn’t see it happening in Europe. So we left it in the set, and when went to Portland, we tried it out, and the minute we started playing it, the front row of the audience jumped up and started dancing. It was really stunning. So I thought, ‘Wait a minute! Maybe I was right!’ You know, audiences are different everywhere, and they’re a lot of fun, and, you know, they’re there for you. I like seeing what kind of reaction we get.

You have a long history of performative songs. Wearing masks, pulling stunts.

Yeah! That’s show biz.

Show biz or just engaging your audience!?

We drove club owners crazy with it. Asking them to turn all the lights off–the exit signs and the toilet signs–and start the concert in the dark. They’d say, “You can’t do that! It’s a fire hazard.” And we’d say [dryly], “The song is three minutes and 40 seconds, can you last that long?” So they’d turn the lights off and it was great, ya know? Start the concert in the dark. And you knew the people were standing maybe three and a half to four feet away from the front because these were punk clubs and you were standing on the stage, and it was right on top of the audience, so you’d get people breathing and whispering and talking, just a little bit away from you, but you were in the dark, and that’s it.

Are you able to do that now?

You can’t do it. You’ve got to think of something else. Anyway, people are so expert at doing that kind of thing, and they’re really good at getting it done, and I’m just trying to figure out the simplest way to get things done.

Well, that’s the way to break the rules now. In an atmosphere where anything is possible at anytime, simplicity is its own challenge. Do you feel the pressure of expectations from your audience now?

No! Because I think what happened is that I used to switch it up so much, and take familiar material and twist it, that people got used to that. I used to warn them that those kinds of things would happen a lot, until they finally got to change their expectations for me. That it wouldn’t just be the same thing all the time, that I would be different every time. And I worked at that. And it paid off in the end. Now people expect strange things. So, I’m happy to give it to ’em.

John Cale’s latest album, ‘Shifty Adventures in Nookie Wood’, is available now through Double Six/Domino.