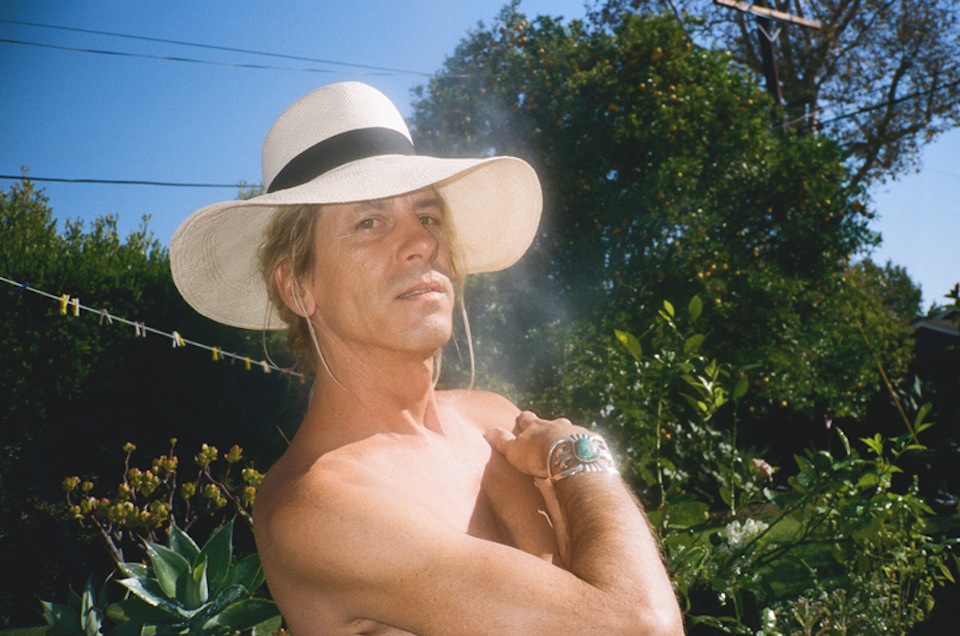

Photos by Magdalena Wosinska

Words by Andrew Parks

“The first thing I did was get cigarettes,” says ambient composer William Basinski, recounting the day he watched the Twin Towers fall from atop his Brooklyn loft.

“My friend and I had just quit smoking,” he continues, “but here we were, searching for five- year-old cigarette butts. I thought, ‘The world’s ending. We’re going to have some real cigarettes.’ So I got them, went back home, and there was chaos on the TV. We turned that off and turned on the music.”

Basinski had recently wrapped his Disintegration Loops series, so he cranked the volume, cracked open the windows and went up to his roof, where he noticed a friend across the way, who had a video camera out.

“It was the last hour of daylight,” says Basinski, “so I asked her to help me frame the camera and let the tape run out. It was just devastating.”

This year, the resulting audiovisual piece was added to the permanent collection of the September 11 Memorial Museum. Temporary Residence Ltd. will also release a lavish Disintegration Loops box set on November 13th. We caught up with Basinski, calling from his LA home, on the 11th anniversary of the day that changed everything…

When did you first get involved with making music?

We were brought up studying music, beginning in the seventh grade. I actually started in Florida, during junior high, but in high school, we moved to Dallas. And my parents put us in a school that had one of the best music programs in the country.

Was it a private school?

[It was] a big public school; we had 3,000 kids, 300 in the marching band, a huge symphonic band, an orchestra, a jazz band. I enjoyed working hard on the clarinet, and then I pissed off my band director in my senior year when I wanted to play the tenor saxophone. [Laughs]

Was the clarinet not your choice of instrument?

It was chosen for me by the band director in junior high. My mom wanted me to take choir, and I said, ‘No, please, I’m getting beat up enough already.’

Were your parents musicians as well?

Amateur. My dad was a mathematician and worked as an engineer for NASA when we were young. He worked on all of the different space programs.

Is that why you moved around a bit?

Yeah. We were in Houston during the early days with the Apollo; I went to church with the astronauts. Then we moved to Florida and dad was working on part of the lunar lander.

So does that mean a lot of his calculations kept things from getting fucked up in space?

Could be. They were all using slide rulers and pocket protectors. [Laughs] The [lunar lander] was made of aluminum foil.

What did your mother do?

My mother raised five kids–four boys and a girl.

Were you the middle child?

I was the second of three boys, in a row…She was a tough cookie, but she did a great job.

Did they try to introduce you to music earlier than seventh grade?

I remember taking piano lessons when I was really young and in Houston–maybe 5, but I didn’t like my teacher. He kinda scared me.

Is it true that one of your parents wanted you to play banjo at first?

My dad teased me about that. My older brother had gotten a guitar and we were all into the Beatles, old enough to have seen them on Ed Sullivan and that was it–the world changed. My brother started playing guitar, and I wanted one, but my dad said, ‘How about we get you a banjo?’ I was like, ‘Ew!’

Why didn’t you fight to play the guitar?

I don’t know. When they said no, they meant no.

So did you shift to sax because you’d discovered artists like Coltrane?

More like I wanted to be David Bowie instead of a first chair clarinetist for the philharmonic, which is what I was being trained for.

So Bowie was your gateway out of the classical world?

Yeah, you know, ‘rock ‘n’ roll’. And then I [went to] North Texas State University, a big music school outside of Dallas. It had a real strong big band program in the late ’70s…When I went to audition, I heard these guys play stuff I’d never heard before, and I got so nervous, I just fucked it up real bad. So I didn’t get into any of the big bands, and changed my major to composition and started on that path.

But you mostly listened to rock records at that time?

Yeah, I was never much of a record buyer. My older brother always bought them, and I had a friend who worked at a record store, so he always had everything. He had his parents’ old car–a 1962 Lincoln Continental, baby blue with baby blue leather interior, just huge. So we could fit eight people in there and cruise around Dallas really slow, listening to Yes and Gentle Giants and all the latest trippy, weird stuff. Bowie, Elton John, you name it.

So did you end up finishing the composition program?

No, I stayed there for two years, and had some really great classes and teachers, particularly in the experimental music program. They taught me about people like [John] Cage, which gave me inspiration [to try] a lot of weird things. I started using tape and did this one piece with electric piano and a little portable cassette deck. It was pretty successful for a sophomoric experiment. Then something happened in my life that changed everything. My friends at that time were all in the art department on the other side of town–all of these gay people, that really fabulous Rocky Horror crowd. They had a friend named Jamie who was sort of the king of the art scene there, but he moved to San Francisco like they all did at that time. But he came back to visit and we fell in love.

So you met him in Texas?

In Denton, Texas. I ended up moving to San Francisco on Halloween in 1978.

You literally jumped on a plane on Halloween?

Yeah.

Was this symbolic in any way? Were you wearing costumes on the plane?

I had this very “Time Warp”-y outfit on–black wool pants from the ‘30s, black alligator stilettos, white shirt, little tie, and a huge vintage black wool cape with red satin lining, a Cinderella mask, and my saxophone in a teeny suitcase.

That’s all you brought?

That’s all I brought. And the stewardesses were so nice. It was me and like three or four other people, so they brought out the champagne and we just had a ball.

Was that a typical outfit for you back then?

That might have been something to go out in. We were pretty flashy and liked to do what we called ‘wrecking’.

And what would that entail?

Getting dressed up, going out and being outrageous. Wreck faces, you know? We were fashion warriors, you know. Very innocent, but we were crazy.

How long did the two of you last in the Bay Area before you moved to New York?

A year and a half, two years…We saved our money and moved there in 1980. We got there on April Fool’s Day, the first day of the legendary two-week transit strike…

Did you have a place picked out?

No, we stayed with a friend in West Chester. I remember the first day–we both had on new cowboy boots and skinny black jeans, just ready to take over the minute we got to Grand Central Station. God, we ended up walking all over town, and by the time we got home, we had such blisters. I think we went and bought some Converse tennis shoes the next day.

How did the New York of your imagination compare with actually being there?

We didn’t know what to expect; we were just excited to be there, looking for that red desert, post-apocalyptic dystopia. Living on the edge of the earth, you know? And we found it. [Laughs] It was exciting, and dangerous, and dirty, and scary. But we finally found a loft in downtown Brooklyn, near Jay St./Borough Hall.

Did you end up staying there for a while?

We were there for 10 years, then they tore it down to build [the] Metrotech [school]. And that was when we found the Arcadia loft in Williamsburg, around ’89.

How would you describe the loft scene in Brooklyn back then?

Not so much a scene. People were working in their studios. In those days, you didn’t have to be a trust fund kid to mov to New York. I think we saved $5,000 between the two of us.

How long did that last you?

Well, it didn’t last very long. It got us our loft, but then we had to build it out and look for jobs. The loft was big enough for three people, so our friend Roger came from San Francisco and lived in the front…It was a rotten old sewing factory, but we loved it. Our neighbors thought we were from outer space when they heard the music coming out of there.

Your neighbors weren’t other artists?

They were, but people had lived there for 10 years already, and hadn’t even finished painting their walls. We didn’t have a lot of money, so we worked all day, and then we came home to work in our studio. The studio was so fabulous. It was better than any club, so we just kept on working.

Would you play music while he was painting, and vice versa?

Absolutely. The place was big enough where we had a whole lot of space between our areas. He had a huge painting studio, and I had a big old table in the back with tape decks, a shortwave radio, some cassette recorders and little echo things. We were just doing our mad science. I remember one night in particular, where Jamie was in his studio and I was working on “The River.” Well, that happened in one go, and I remember having to go to the bathroom in the middle of it, so I tiptoed through the loft and had to go past the door of his studio. I looked in and pointed to the back. He was like, ‘Oh my god!’ And I was like, ‘I know!’ It was incredible, just really magical.

What else was done during that period?

A lot. I was very prolific back then–from like ’83 to ’84–Shortwave Music, The River, Variations. My neighbors had a piano, so I was experimenting with tape loops and that during the day. It was John Eppperson’s piano. Do you know him?

I don’t.

Have you ever heard of “Lypsinca�

I have not.

Well, John was one of the first people we met [in New York]. He’s a really famous female impersonator. He does really crazy, fast edited lip-syncing, usually focused on a particular Hollywood star. Like right now, he’s in San Francisco, at a cabaret doing a show called “The Passion of the Crawford.” His shows are just insane; he’s a really mad Southern queen who does this crazy ass shit. But anyway, at that time, he was the rehearsal pianist for the American Ballet Theater. So during the day, I could play on the piano while he was gone. I did a lot of pieces during that time that’ll probably never be released. And there’s some that may eventually get released.

How much time passed between your time in college and when you eventually figuring out your whole aesthetic?

Well, I left something out. Jamie heard that [college] piece when he came to Texas and he was so [supportive]. He’s someone who’s always worked at record stores and been a collector. He has to have everything. And he does.

So you’ve never had to buy records?

Never. I don’t know what to do in a record store; just look at the boy’s arm next to me or something. I don’t know. But Jamie said, ‘This is incredible; you’re a genius.’ And of course that was very attractive to a young kid who nobody paid any attention to down there. So anyway, we’d listened to records a lot, and he had all of the old German experimental music, as well as classical and early 20th century…he had everything. He’d come from the record store every day with arms full of records. There were two records that really set me on a path that was an epiphany where I thought, ‘Oh, this is allowed.’ There was Steve Reich’s early work, with his tape and feedback loops, which was interesting to me in terms of what I’d already learned with John Cage and stuff like that. And then there was Brian Eno’s Music For Airports–its melancholiness really hit me on the head. I thought, ‘Wow, okay.’ It was all about listening to the albums and figuring out how they do everything. Like I think there’s a diagram on one of Fripp & Eno’s records where they show you how the tape loop was done. You could find tape decks at any junk store down there for $5, so I just got a bunch of junk and started experimenting with it. I wasn’t worried about whether it was good or not; I was just trying to see what I could do. And things just happened that encouraged me.

What had you done before that?

Before that, I’d done some prepared piano. I also had a teacher who’d taught us how to really listen, which is one of the most important things–how to stretch your ears. I listened to everything. We had a great old refrigerator in San Francisco. It made this incredible sound, especially in the freezer, so I put a microphone in there, recorded it and slowed it down. Oh my god; all of the overtones from that were so fantastic. So yeah, I tried a little bit of everything.

What was the first recording you were especially proud of from that time period?

Probably some of the early Melancholia loops and A Red Score in Tile.

Did you come to a point in the late ’80s where you felt like you weren’t getting any recognition, so you shifted your focus to building your Arcadia space in Brooklyn?

A little bit. I got a call in ’83 from some old buddies of mine in Denton, and they were music directors for an RCA project. MTV had just started, and they were doing a video, so they needed a sax player and asked me if I wanted to do it. I said sure. At that time, they’d do like five bands on a sound stage, wham bam thank you ma’am and then you’re done. The day we were there, I met the Rockettes. They were the first great rockabilly revival band from the UK. I was talking to Smutty Smith and said, ‘You guys need a sax player; I’m your guy, so here’s my number.’

A few months later, they called me. They were putting some shows together in New York, so they asked me if I wanted to audition. I did, and I got the gig, so I did some shows. I think they called me ‘Rockin’ Willie B, the New Rockette.’ Later that summer, they called me again because this band had cancelled opening for Bowie on the Serious Moonlight tour. The Rockettes got the gig because they were on the same label, so I got to play with them in front of 30,000 people in Hershey Park, opening for Bowie. And I got to meet the Bowie, and to watch his show from the wings.

By ‘meet the Bowie’, do you mean a brief handshake or actually hanging out?

No, no, no. Just a stunned hello. I was much too shy to wander over to his dress room or anything nervy like that. Eventually, I started playing with other people…I kept doing my experiments though.

Did you work with a good mix of rockabilly and no-wave acts?

Each one was different. I played in a weird rockabilly band with the former director of the New Museum. It was just him and me and some awful drum machine. [Laughs] It was crazy. So I played in a bunch of bands, and eventually, when we moved to Arcadia, everything got packed up and I had a chance to build a real studio with synthesizers, a console, a control room, and a little stage at one end of the loft. At that point, I was trying to do something a little more accessible–a song suite called “Hymns of Oblivion.” The lyrics were from Jennifer Jaffe of the art installation group Tote. They were one of the first art installation groups of the ’80s who had a big following.

Were the lyrics prepared for you?

No, she just wrote a stack of poems and gave them to me. I’d just pull off one, get an idea and start going with it.

Like spoken word?

No, I was singing. I worked on that for a few years, and then I started producing other bands. We wanted to share the loft. It started as a ruin full of pigeons, but it was an extraordinary building with vaulted, Gothic ceilings and just beautiful sound, like a perfect Viennese shoebox theater–no standing waves. We restored it within an inch of its life, and it was just this beautiful palace.

Were you that handy?

Living in New York, you learn to be a little handy, from cutting hair to working with sheet rock. I actually helped install Andy Warhol’s first retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. So yeah, we restored the place ourselves and I had help with the sound room from an engineer friend of mine. It was wonderful. We did shows there for about seven years–Diamanda Galas, Antony got his start there.

Was he still performing with Blacklips then?

I saw him with Blacklips, yeah. I was so impressed with his music that I went downstairs to talk to him [afterwards]. I told him how much I loved his music and that I had a studio he could come by, and he did. We hit it off, I helped him with a demo and we started putting on shows.

Did he perform solo?

Yeah, with a piano.

Was he from another world back then too?

Oh my; Antony was always unique and incredibly focused. He knows exactly what he wants, to the point where he’ll drive you to dementia over any little thing. But he always gets what he wants [laughs]. I just love Antony. I’m so proud of how far he’s gone, It’s amazing.

Has it been weird seeing what some of your friends had to say about you in the box set? Is it like an episode of ‘This Is Your Life’?

[Laughs] No, it’s great. [Antony] was one of the first people I called when the Disintegration Loops happened in late July, early August 2001. I was like, ‘Get over here, you won’t believe what’s just happened.’ At that point, he’d gotten some attention from England, so he spread the word over to David Tibet, and David Tibet told everyone at The Wire. David Keenan wrote a beautiful story that just kinda launched it.

When did the Disintegration Loops project develop then? That summer in 2001?

The last couple days of July. I had closed my store on the first of July. That whole thing crashed with the internet bubble in August of 2000.

What kind of shop?

I had a vintage shop called Ladybird on Bedford Avenue for three years. It was right around the corner from where I lived. Everything was telling me ‘you need to stop messing around with purses, old shoes and couches, and if you don’t concentrate on your work, nothing’s going to ever happen. You’re going to be an old, drunk antique dealer who won’t let anybody come into the shop.’ [Laughs]

Had you basically stopped doing music by then?

No, I was still doing music, but it wasn’t going anywhere. I had a couple releases, but they kinda evaporated. Like in 1998, Carsten Nicolai released my first record on LP, Shortwavemusic. I didn’t even have a laptop I could go online with until 2001, during that summer. I was close to getting evicted then, so I was really stressed out about it. So anyway, there was this beautiful day, and I was sitting in the sun in my bedroom, reading this little turquoise book The Way of Zen, which made me laugh. It was like, ‘Get a grip. Use this time you have to do your work.’ So I decided to continue archiving these loops. I put the first loop in line on, and it was “Disintegration Loop 1.1.” I was blown away at how beautiful, grave and stately this melody was. I didn’t even remember [making] it. There were times in the early ’80s when I was making these loops and would record something, slow it down and it’d be so flawless I knew nothing needed to be added to it. But I didn’t know if I could say it was my work. It kinda scared me. So [“Disintegration Loop 1.1”] got set aside on this dead tree I used to hang the loops on.

You were literally hanging them from a tree?

Yeah, I had this old tree in the studio that had all of these old branches. It looked almost like a brain, where I could group the ones that went together in certain sections. Eventually those got packed up, because in those early days, I wanted to be more involved in mixing and doing other things–being involved. When I heard [“Disintegration Loops 1.1”] again, I thought it had to be my new piece, that it was just what I needed. So I started messing around, adding a French horn as a counter melody and turning on the CD recorder. I set the levels, turned it on and went to make some coffee, and when I came back a few minutes later, I could tell something was changing. I could see the dust in the tape path, and I thought, ‘Oh my god, this is what I was afraid of. What’s gonna happen now?’ That whole loop did what it did for the entire length of a CD. It collapsed in its own beautiful way.

I continued on from there with the next loop and another counter melody. By the middle of that one, I realized, ‘Wait a minute, we don’t need counter melodies here. We need to let these things do what they’re doing and get out of the way.’ Monitor but don’t try to fuck it up, you know? So over the rest of that day and the next day, the whole thing–all six loops–had done their thing. I was just shaking, calling all of my friends and saying, ‘Get over here. You won’t believe what happened.’ I spent the next two months just thinking about the life and death of each individual loop. It was as if they were redeemed in a way. It had a very profound effect on me, then I just listened and listened and listened.

It sounds like you had a lot of loops lying around. How did you decide which ones would be a part of this series?

Well I had found all of these cases in a storage area in the back of our loft. It was called The Land That Time Forgot. There’d be little lunch boxes or takeout containers, and as I remember it, I had a boom stand in the studio where this next batch of loops was hanging. I just pulled the first one off and put it on. Then I went on got the next one, and the next one. The order they’re in is the order they came off the stand.

And each piece was one literal loop?

Yeah, of varying lengths.

So what was the shortest, and what was the longest?

The shortest one was about six or seven inches long, and the longest one was maybe 15 or 16 inches long.

What does that translate to in actual time?

Not very much. I mean, you can tell when you hear it. [Hums melody] It’s like four bars or something.

It’s amazing that they’re that short and yet, you could have let them play for six hours if they let you.

That’s what I used to do. When I thought a loop was successful, it was the kind of thing you could put on for hours…I liked when the loops were seamless, when you couldn’t hear a beginning or an end. It really just became this eternal thing. The reason I’d made my pieces so long, where I’d use the whole side of a cassette or something, is because they were meant to last forever. Like “The River†was 90 minutes; it was two sides of a cassette, meant to go around and around and around.

I’m not sure everyone understands how this series developed. Did you finish the first volume on September 11, or the last bits of the entire thing?

I made the work in early July and late August, then I was just listening and listening and listening. On September 11, I was going to try and get a job at Creative Time, which had an office in the World Trade Center at that time. They were looking for an administrative assistant, and I knew those people–they had been early supporters of mine–so I was going to try and get it. But then when I woke up the next morning, it had already started. Then the whole world changed. We were just stunned and horrified, just in utter shock. After sitting on the roof and watching the towers collapse in slow motion in front of our eyes, we just…I mean…you know…Were you there then?

I was still in college actually.

Well, it was one of the most beautiful days you’d ever seen in your life–a crystal clear, autumn, gorgeous day. And we could see the World Trade Center from my bedroom windows.

You were about a mile away right?

A nautical mile, yeah…It was just a nightmare. So we put the music on really loud and went up on the roof, looking at all the smoke and thinking, ‘What…the…fuck…just…happened. Oh my god; here we go–Armageddon, the greatest show on earth, is starting. You fuckers.’ My neighbors got a little freaked out when “Disintegration Loops IV” came on. It’s the one that really catastrophically collapses.

It’s almost like it’s gasping for air, yeah.

Right. So my neighbors came running up the stairs and yelled, ‘Turn that off!’ ‘Sorry!’ Then I went to [my friend] Peggy’s house; she had a video camera up on the roof next to me. It was getting to be the last hour of daylight, so I asked her to help me frame the camera and let the tape run out. I got the tape from her in the morning, put it in iMovie, and added “Disintegration Loop 1.1.” It was just devastating.

Is it impossible for you to feel disconnected from that day every September 11 because you witnessed it first hand rather than through the TV?

It makes a difference; it really does. Everyone who was in New York…I wish I could forget about it. It was just horrible. Everyone was losing their minds in one way or another, going into their own “Disintegration Loops” of sadness and fear. I don’t know; I wish I didn’t have to talk about it again. It was such a horrible day. And I don’t buy the official story or anything. It doesn’t make any sense.

It must be a mixed blessing for you, to be regarded for this work of art and how it relates to September 11. Almost like a curse in a way.

It is, but I can’t complain, not when all of those poor people were murdered that day. I don’t know…The fires didn’t even go out until Christmas or so. And the smell was so hellish, it would make you sick. It would bring you to tears when it came your way. I felt like this has to be an elegy, almost like how Jacqueline Kennedy wouldn’t take off that pink Chanel suit after the President had been assassinated, even though it had blood and brains all over it. For three days, they were desperately trying to get her to change and she was like, ‘No, I want them to see what they done.’ It was very brave.

Did you have a hard time plunging yourself back into your work as an artist then? Or did you feel more driven?

There was such a sense of anxiety, shock and fear immediately after, but I’d been working on this beautiful work all summer. I thought I should make sandwiches and bring them down to the firemen but then I thought, ‘I can’t do that. I have to just do my work. It’s what I’m here to do.’ I just had to go through a dark night of the soul to get there. The weird thing is that I was losing it the night before September 11 because I knew I was going to get evicted and was so heartbroken about working hard for so long and no one ever getting what I’m doing. And here I had this magnificent piece of work I didn’t know what to do with. I called Jamie crying, threatening to kill myself, and he talked me down, and I went to bed.

Was he living in another city then?

He was living in L.A. then. That’s why we’re here now–because he had a job out here, which he’s retired from and now he lives in Beijing [laughs], doing his work over there because that’s where his interests lie now.

Did you still consider yourselves together at the time?

Yeah, but I was going through that whole thing of ‘you left me, blah blah blah’–the whole works…We’ll always be together. We’ve been together for 30 years, so it’s different; we’re life mates and we love each other, and we encourage each other. There’s nobody like Jamie.

Do you still work together?

Yeah, he’ll send me stuff. It’s best when he’s not [in L.A.] because I’m a good editor and he likes to hold onto everything.

Is any of that getting to a point where you might officially release something to the public?

I’d like to release this Variations film we worked on. I’ve got a lot of things I need to get done, but I’m still here by myself doing it all so it takes a long time.

Have the last seven years or so been a bit of a kick in the ass then?

Yeah, it’s great. I never thought I’d live to see the day. On September 10, I thought, ‘This is it. I’ve lived too long, No one’s ever going to get this. Fuck it.’ But now, I’m so thankful and happy to show up for work. I’ve been touring a lot the last few years, so that takes its toll, but you do it, and that’s great.

Do you still tote all of your tapes around in lunch boxes?

I do. What’s been great is seeing The Disintegration Loops become part of the orchestral repertoire. Like Antony invited me to close the Meltdown Festival last month with a 40-piece orchestra.

Did you conduct it then?

No, we had a professional do it. Ryan McAdams is this young rising star that we were introduced to by Ronen [Givony] from Wordless Music last year. He got the ball rolling, and then it got picked up by the Met a year ago. I was just blown away by what I saw there. Did you see it?

I wish I had. Wasn’t it in the Egyptian wing or something like that?

In the Temple of Dendura.

What was that like–seeing something you composed with tapes transposed into an orchestral piece?

[Arranger] Max Moston is a genius. He did the most incredible arrangement. We had two rehearsals in the little theater they have at the Met. What I found so interesting is when I thought of a note, Ryan the conductor would stop the orchestra address that note in a very interesting way. I thought, ‘Wow, okay, I’ll just have to make a few mental notes and see what happens.’ Eight hundred people ended up showing up; I think about 400 couldn’t get in. It was unbelievable. And then people sat there for almost three minutes in stone silence. There was literally no sound, and then this motorcycle or something went by and brought the F-tone drone back in and out. That’s when everybody just went crazy. I was so happy.

It must have been hard for the musicians to mimic the sounds of a decaying tape loop.

It’s very difficult physically to do, but Max is such a great orchestrator, he knows what people are capable of. He’s just got such an ear. This summer he worked on a treatment for “Disintegration Loop II,†which premiered at Queen Elizabeth Hall with a 40-piece orchestra and a one-day rehearsal again. We had sold out Queen Elizabeth Hall–this beautiful setting that sits about 1500 people, and by the end, it was like we, in honor of John Cage’s birthday, added an orchestral version of “4 Minutes and 33 Seconds” because they outdid New York with the silence at the end. So anyway, I’m just beside myself with joy about the work going into a place where it can be free of other connotations and just be part of the orchestral repertoire.

So what’s the next step, especially since you have the box set coming out now?

I have a friend working on number three, and I talked to Jim Thirwell in London about doing number four. He said he’d love to, and Max said he didn’t mind. So I want to get those done, and some other work as well. In the meantime, I’ve got a record I need to release. It’s called Nocturnes.

You need to tell me a little bit about that beyond what it’s called.

The title piece is the first piece. It’s really old, and very different, coming from some of my earliest influences. A very triply, weird piece, made with eight or 10 loops, and I scored it with a graphic score.

It’s not as soothing as your other work then? It’s a little more psychedelic?

A bit. The second piece is newer, and it’s also pretty dark. It’s called “The Trail of Tears.†Part of it was included in the Robert Wilson opera The Life and Death of Marina Abramonivic. That was a great experience too. It’s a great show. So I should have that finished soon. It’s two pieces; one of them’s 40 minutes, and one of them’s about 20 minutes.

Are you going to keep putting stuff out through your own label?

Yeah, it’s the only way I can make any money.

Don’t you want to reissue some of your other records on vinyl too?

Yeah, but you never make any money from that. I can’t do anything with a couple of records; I’ve gotta pay my bills…I don’t know. I’d like to start releasing more things on vinyl, including this one. I’ve been listening to Nocturnes and trying to shorten it, but I haven’t figured it out yet…I’m going to try and get it out this year, but there’s so much else already coming out, and not everyone’s going to be able to afford the box set, so we’ll see. There’s a young guy from Bloomington, Indiana, that has this little boutique label called Auris Apothecary. They do cassettes and reel-to-reel releases. He sent me a mockup of the 30th anniversary of Shortwave Music on a reel-to-reel, with a typed parchment letter and a waxed seal. It was so cute. He wanted to do an edition of 150 of those, so I said, ‘Okay, we can do that.’ So I’m trying to go through my archives from that period and find any ephemera he could use for that release.

I have one bigger question for you to close things off. Earlier on in our conversation, you mentioned feeling guilty about claiming ownership of your loop-based work, especially since it essentially takes on a life of its own. When did you start to feel like the music was inherently yours, as opposed to something that took on a life of its own?

I guess it was the time, you know? In those [early] days, there wasn’t any context for what I was doing. People would come over to hear my music and not even know what jt was. I work in such a loop myself. Everything for me is so ephemeral. Like it frustrates me every time I’m editing something for years and then Apple suddenly changes its operating system. It’s like, ‘Rarrr!’

Whatever happened to the ‘accessible music’ you were working on in the ‘90s?

I never put it out. At the time of mixing it, I never synced the MIDI tracks and eventually the computer I used to make it died. So all I have now is the mixes. Some of it’s okay; it is what it is. Maybe I’ll release it sooner or later, but it’s kinda embarrassing [laughs].

What does it sound like?

Very gothic.

And you’re singing in it?

Oh, I was singing and playing all of the instruments.

So this is your 4AD record?

Exactly.

–

This interview was originally published last fall. Read the rest of it or buy the enhanced tablet edition here.