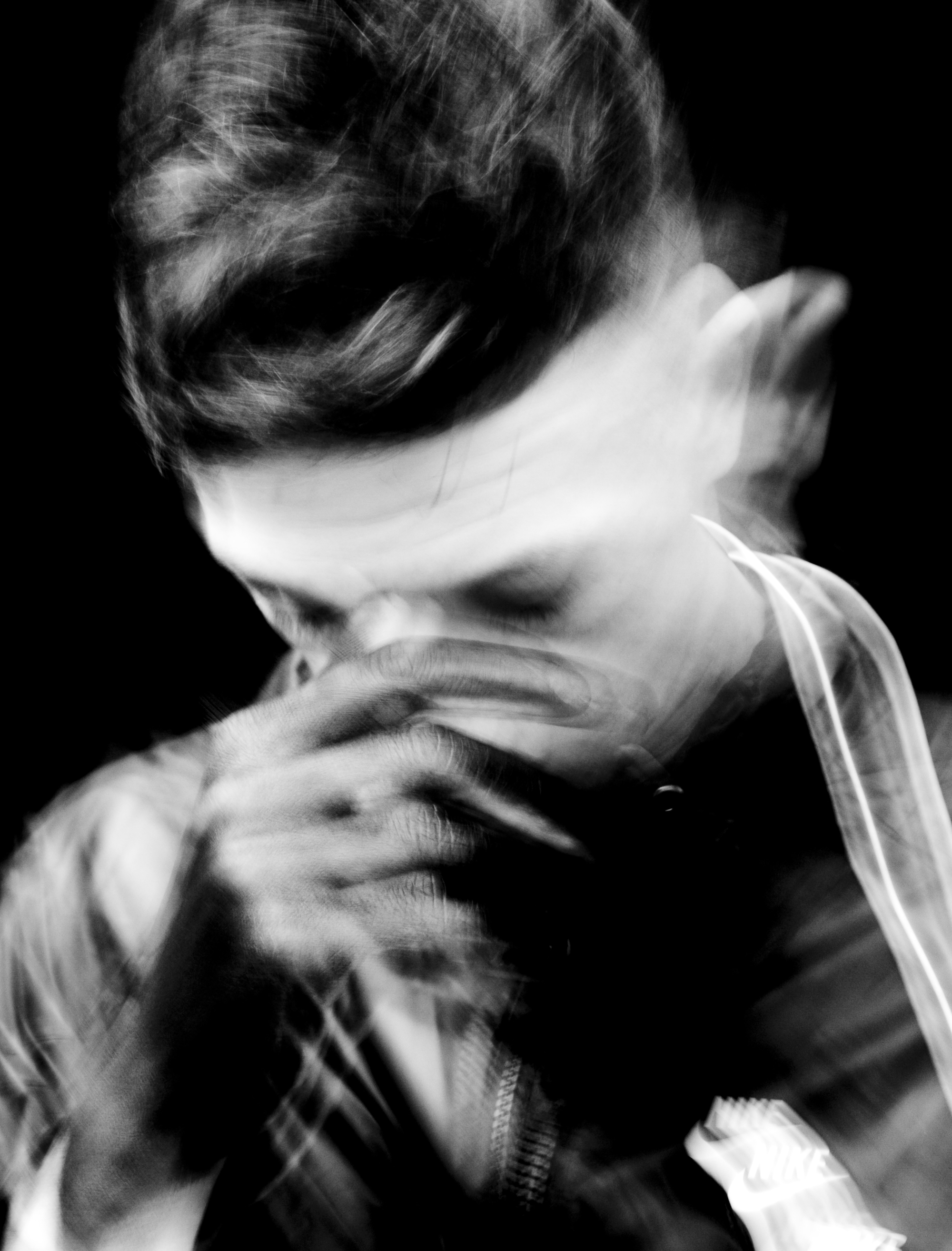

Photography JESSIE CRAIG

Words ANDREW PARKS

When self-titled confirmed a rare Zomby interview around his Dedication album, I expected some eccentricities; the elusive producer shields his face in photos and prefers lucid iChat exchanges over in-person interviews. What I didn’t anticipate was brutally honest quotes like this: “I thought we were all gonna live forever. I was in a dream world–never broke a bone in my body; never saw my dad ill; never took a day off work. It sounds stupid now, but that’s life, isn’t it?”

Indeed. And the brute force of how it all usually unfolds really hit home as Zomby dealt with his father’s death and tried to process all the personal and creative pointers the fellow musician had given him over the years. While the melancholic, mercurial shades of Zomby’s long-awaited new LP weren’t directly influenced by his father’s passing–its shape-shifting songs came first–the entire thing is true to its title, a literal tribute to the unspoken connection many fathers and sons have.

The following is an uncut version of the story that originally in our digital magazine. It’s not the entire conversation, though; that’s more than 10,000 words and three hours of iChat transcripts that are rambling and revealing in all the right ways….

self-titled: How about we start by talking about non-musical influences on this record?

When I started out, my influences were prominent–like Wiley and grime. It all helped me learn, but now I just write from a clear head. What inspired [Dedication] was things like Givenchy street casting; the way it creates a dream for some people. That’s what Zomby is about for me–a little bit of imagination that’s alive. Maybe Zomby is sitting next to you on a train or a bus stop, or maybe I don’t even exist.

There’s definitely an immersive quality to this album; more so than ever before.

It’s more introspective, ‘cuz i stopped writing music for [other] people. The value of intent changed, which wasn’t conscious to be honest. It had a lot to do with being pushed out of scenes I hadn’t asked to be part of, and also to do with my father dying of cancer suddenly. All of a sudden, you’re completely alone no matter where you are. Man, that sense of sadness hit me right away:It’s sad ‘cuz my dad wont hear it, so I dedicated it to him.

Did your father pass away recently, or right before you started making the album?

Just along the year it was being compiled and finished. It’s nothing to do with that. My music and my [personal] life are separate, but the time and work [put into the album] is in dedication to him. my work was dedicated to him but this one’s overtly so. It’s not the titles or whatever; it’s a lot deeper than that.

Is he where you got your work ethic?

Yes. My dad never took a day off work. He just had two kids, got married, and worked hard; got us a nice house and lifestyle:He had dreams. He’s more talented at writing music than me, but I get the chance ‘cuz he sacrifices his life for his family. That shit isn’t a joke. That’s what real people do.

Devote their lives to their family you mean?

Devote yourself to something wholly, with no compromises and no regret. How can you work your whole life and die of cancer never having achieved your dream? Of course, my dad’s dream was a successful family. When it’s someone so close, you might not see it, but actually all you have to thank for is there. Like my dad would explain things to me philosophically as a child. I didn’t realize until later how much wisdom I’d been given.

Just general thoughts on life?

Yeah, and science and nature. How things work, you know? It sounds dumb, but it’s actually how you reason things in your life. To be honest, after my dad passed, I didn’t have any realization. I knew [what we gave me] all along. I was really close to my dad. I miss him like fuck. Obviously, there’s nothing I can do but carry on, so here I am. I’m not dealing with it well all the time. Fuck it; I don’t care. It’s natural–life and death–so here I am:

Was your father an artist too?

Yeah, he had a band and wrote the songs, etc. He was fucking good, of course; recorded at Abbey Road before me, anyway. Just instant how he could do it–pick up a guitar and write a melody or lyrics.

Since you’ve kept at it for so long, do melodies come to you more naturally now as well?

Yeah, I’m almost a savant now. [Laughs] I just sit in front of the piano and feel it out. I had [those instincts] since I was a child, though; I always knew I could write music.

There’s a really natural pop sensibility to your new record, for sure.

That’s right, really. I would like to take the journey of Zomby to a larger audience now without sacrificing any integrity. I feel I’ve covered a lot of areas artists wouldn’t reach. I try to write on the edge, to be honest. Once music is discovered as a style, it loses its charm. So I try work in the middle ground where the songs often ripen a year later. Like a lot of the work just ripening now was written two or three years ago.

You also seem to run with your ideas, even if that means a song is erring on the edge of classical or whatever.

You have to. The music follows itself. You’re just witnessing it, really. It depends on how much you want to give to the sonic [details] or the musicianship. There’s value in ignoring both at different times. [Laughs] At the same time, you have to know both well enough to form a tight movement. It’s like a backflip to a ballet dancer, or breakdancing. I may look like a b-boy, but I prefer the ballet.

Going back to your dad really briefly, beyond learning how to have a solid work ethic from him, did he share a lot of records with you when you were young?

Is this the interview?

It can be. I love when interviews become real conversations.

Okay, just edit what you want from this… Yeah, [my father] shared a lot of great music with me. Looking back now, a lot was way over my head. He was Brian Wilson mad, really. I was taught all sorts of things early on I had no idea the value of.

Way over your head, songwriting wise?

Yeah, he’d explain to me why this or that’s important, while I wanted to just go play football in the park.

Give me an example of what you mean. Just really detailed studio tricks?

Not studio techniques; more like sonic tricks, or an appreciation for things you wouldn’t normally look for–advanced listening, really. You can be taught a gift and not even know it. An artist can show you how to look at a painting; my father showed me how to listen to music. Like listen; not just passively absorb it. Like he’d ask me who’s playing what in a band, so [I] tuned my ear to the instruments.

I think my dad spotted me as a small child playing keys and just thought maybe that’s strange. I’d stand hitting keys and playing with the reel to reel. I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing but you’re playing as a child with toys, aren’t you? I just thought it was fun to play with keyboards. I do the same thing largely now. [Laughs] My dad always encouraged my music interests, you know? I was obsessed quickly, so I needed that.

And you never wanted to play with other people like he did?

That’s right. I never had any interest in being in a band. I think that’s why I got started later, rather than as a teenager–’cuz I didn’t have a clue how to wire up a studio. I’m not a computer type person.

Did he help you get your studio sorted in the beginning?

He didn’t help in that way. He’d go half with me on a Mac or a soundcard, he bought me some turntables for my thirteenth birthday, etc. [Music] was no joke to me, even at 13.

Was your father into electronic music?

He liked electronic music, yeah–anything well written like Kraftwerk, for instance. He’d also ask me what certain dubstep tracks were all about–the super heavy shit. He thought they were funny and obtuse. He loved Wiley’s beats. [Laughs] He’d sit and listen to pirate radio with me as a kid. I’d have lines shaved in my hair, wearing a [tracksuit], obsessed with it all.

What did he dig about Wiley’s beats?

I think he loved the sonics and momentum. He could tell originality, I think. It was the underlying notion of his taste.

Was he critical of your early stuff in ways that were really helpful?

Yeah, he understood me well. He’d leave me to it at certain points, of course. Music to me isn’t a joke. I love it so much; I just disappear for weeks into music. He was critical of me, yeah. [Laughs] That was quite funny. It rattled me, ‘cuz I was so scared to play anyone my music. My dad was the first person I shared my plans with. I remember saying to him one day, ‘I’m going to have my stuff played on pirates, then raves, then I’m going to put records out.’

He must have thought your Where Were U In ’92? record was pretty mad sounding.

He was probably thinking, ‘Where did I go wrong?’ [Laughs] He loved that record, though. See in England, we know that music well. There was a time when that was all there was and it was quite a while.

Maybe that record reminded him of you playing mixtapes when you were young.

Those were the sounds we’d sit and listen to from pirates. He knew it was a serious childhood influence on me. It did remind him of [me] playing those tapes; that’s right. It must have been beautiful for him to hear that, really, ‘cuz that was my first record. I wrote some on the Atari I first bought to write beats on [when I was] 14, too. I never got it working properly because Cubase was difficult. When I did, I was 25 and writing that [first] record.

Did he have a knowledge of how to get that technology to work or was it more foreign to him because he was more of a band guy?

It was a bit of both, but as things went digital, I think we both got lost. [Laughs] I was close to my dad. I’d go to music shops with him; look at gear, etc. We’d have fun playing things and laughing about how expensive they were, as I plugged in a MiniDisc and sampled what I need. My dad was cool as fuck; I can’t explain it.

My work blew him away a bit ‘cuz of the amount I’d make. I’d give him a CD to listen to while writing another 20 beats. I think he couldn’t work out how you could make so many on one laptop. [Laughs] I love my family. I’m as close to them as anything else in my life, but as you get closer to your work, you forget how much certain things mean in your life. When you’re in the atmosphere again, it makes it twice as precious–the time you get alone with them.

Do you live close to your family?

Nah, I left home at 17 and moved to the South of France. I came back to England at 21 and went to live in Brighton, then back to London. I went back to my parents’ house when I was, like, 25 to say hi. [Laughs] Then I stayed really close to my dad, obviously, bonding again through music.

So music is what brought the two of you together more than anything when you went back home?

Yeah, and being men, of course. As a man, it’s different. When you’re a child, you’re so immersed in growing up. When you’re grown there’s time to see other things in people.

See that deeper side of everything, you mean?

Basically. Duality.

You must feel fortunate to have such a close relationship with your family, since it’s such a rarity these days.

My music has no place in that. They don’t really know what I do; only my dad was involved. I think they think I sell drugs, to be honest.

Because they just judge you on appearance?

Yeah, and I don’t live a regular lifestyle. I’m comfortable; I’m out shopping for diamond rings for myself, and they call security to watch me. [Laughs] I’ve got $3,000 wrapped in elastic bands in my pocket, a Rolex on, and all Supreme clothes; they still call security. In England, if you’re from where I’m from, you don’t shake it. Where do you live?

I’ve been in Brooklyn for about six years, but I grew up in Buffalo, so I traveled to Toronto to go to the jungle parties there a lot.

Sick.

Yeah, that’s why I understand you being obsessed with mixtapes when you were 13.

Yeah, man; although a lot of the tapes I would be after were rap. Like Lord Infamous, DJ Paul and Juicy J, Tommy Wright III–I collected most of those like a nerd. I can’t listen to much hardcore [techno] anymore.

Happy hardcore was a bit out there, no?

Yeah, I didn’t like it. That’s when I got into jungle hard; about the best time, to be honest, ‘cuz the music became so dense it created its own world. I couldn’t believe how good the tunes got.

Jungle hit a wall creatively, though, just like dubstep has. There’s just so many ways you can use an ‘Amen’ break or sub-bass sounds.

Such a fucking shame, man. I loved dubstep. I loved the swamp and myth of the space.

It’s unfortunate that people can’t apply some of those elements to more experimental stuff. That’s why I love the classical influence on your new record. Are you actually playing the piano on it?

Yeah, I love the piano. It’s the closest I can get to the music, like I can nearly be absorbed by it.

Well it just makes it so much more visceral suddenly, you know?

Exactly. It’s like being in the fucking Stargate.

Do you know music notation?

Sometimes I’ll just do it all freehand; sometimes with notation. Sometimes I can see the notation without having to write it, and just crack on which has become the usual process, if I’m honest. It just takes too long to take a piss, let alone reach for a pencil. It’s really not that relaxed.

I know what you mean. The best writing just flows through you.

Automatic writing is as good as it gets.

Was this record culled together from tracks from the past few years then?

No, an 18-month period, I think. I don’t consciously sit down to write a record unless it’s in one style. And then it’s a struggle to do it and not get distracted with something else. I’ve done it with hardcore, grime, and I’ve also hidden a jungle album; there’s thousands of songs, really. I love to write them.

You’ve kinda laid low since your last mini-LP (2009’s One Foot Ahead of the Other), though.

I didn’t lay low. I just started to be approached for a album deal, so I took my time. I had offers from fucking everyone, man. It took ages. If it was up to me, I’d have released about nine albums by now. Believe me.

Couldn’t you do more low profile releases of stuff like jungle?

I could do that, but I want all the work for Zomby. It’s all part of one world. I won’t use aliases. So many people bite my sound, it would cause too much confusion. When I write, it’s for Zomby. I’m not Zomby; I’m the artist.

So it’s almost like when Bowie was writing in the guise of Ziggy Stardust?

Nah, I suppose I am Zomby. The attitude of the work is my own, I guess. ‘Cuz otherwise I’d alter it to cash in. As it stands, I quite like it to have its own life.

One thing I’m curious about is what you think of how much modern R&B is working its way into people’s productions, like the first single from your album, “Natalia’s Song.”

Well, it’s British R&B, really. R&B isn’t as obvious as people think, usually. A lot of the stereotypes are wrong. The kids aren’t as dumb as they think. Someone who’s 50 might say that’s dance music, and someone who’s 16 might just hear the beauty of the intent of the song. Something like Burial is as much R&B [as anything else] in that it hits the same emotive quality that a gushing ballad does.

Younger kids don’t see the genre distinctions you mean?

They don’t care to see them. It all blurs. All distinctions are fine until they become restricting. And you only find that in older artists who are trying to protect an area of revenue. No one else cares, really. I mean, no kids care whether [Waka] Flocka [Flame] is rap or hip-hop or whatever. They just wanna hear him shout “BOW BOW!” ‘cuz the music’s sick.I can play Philip Glass to a kid like that, unless he’s like, ‘Oh, that’s some old school piano shit.’ Then the attitude’s wrong. To be honest, I couldn’t care what color the chick is if she’s pretty. Know what I’m saying? She could have blue fucking hair. I don’t give a shit. If I like it, I like it.

When you think of life in that way, everything’s limitless isn’t it?

Yes. Then intuitive connections become analogues.

Even though you’re dad was from a totally different generation, it sounds like he instilled some of those ideas in you, too.

He did. I sorta have personal revelations about things he said or taught me.

What’s one recent revelation?

You often ask yourself why this or that, but the knowledge comes later when it’s your turn.

You talking about hindsight?

Not specifically. [Laughs] How you haven’t fucked up. Why didn’t you fuck up? ‘Cuz someone did before you and steered you far away from that opportunity too.

Why didn’t you take more chances you mean?

No. Why was I allowed to take so many risks?

Is the need to take chances one reason you never wanted to be in a band?

I think so. I haven’t time to listen to opinions. I also have a slight inferiority complex in that case.

Do you even play your music for friends?

To be honest, I don’t actually. I don’t really shout about what I do. The ‘net clues everyone up to whats going on. I don’t need to. The work has its own life in a sense. It doesn’t need to be fucked with. I always feel the more people hear a tune before [it’s done] the more it loses its power. Like with “Natalia’s Song,” I wrote it to give to Burial, really. It wasn’t intended to be a single.

Is it almost an homage to him?

Not that. I just thought he’d like it, so I sent it to him and left it. He played it for Kode9 and he liked it too, so then I know it’s got life.

So you had no idea he was gonna play it during his Mary Anne Hobbs set with Kode9?

Nah, I didn’t know. I also didn’t know about Lady Gaga or Prada. (Ed. Note: Lady Gaga used “Tears in the Rain” as interlude music on her “Monster Ball” tour and Prada used Zomby’s music in their fall 2009 show.) I just write the music, but of course I know it has weight in the creative world. I’m no fool:I mean, we can all write, but we can’t all write poetry like [William] Wordsworth. Or we can all run, but not as fast as Usain Bolt. Then to ask what gear you use? Well, I’m not sure it matters.

Gear doesn’t mean shit if you don’t have the ideas.

Right; you need the ideas for sure, but you also need to be able to articulate them. I mean, I don’t think I’m a revolution in music. But is Chanel a revolution in clothing? [Laughs]

One thing I’m curious about is the lyrical side of your music. A lot of this album is so emotional. I wonder if you went into certain songs trying to react to certain things in your personal life. Or maybe you just sit down and that’s what came out.

It’s just what comes out, yeah. Sometimes I want vocals and can’t get them; sometimes I can and don’t want them. If the timing’s right and the song fits, it’s good. The song with Panda Bear (“Things Fall Apart”) was a treat for me. I love his music and Animal Collective, and I thought the song came out really well. It’s exactly what I go for in music–slightly edgy, uncomfortable, warm and coherent at the same time.

Did Noah [Lennox] write his vocals for that track once it was done?

No, we got involved. With “Natalia’s Song,” the vocal was inseparable from the chords. I just do what’s best for the song. I’m a producer in that sense, but not one to manipulate for the audience; just the song.

Maybe that’s why a lot of your songs are short–you don’t over think anything.

They don’t need to be short or long, to be honest. They’re just glimpses of work. The music is just one take. I don’t really sit on loops for hours; I just write the song.

Is a lot of it live/less sampled than people realize?

I sample for texture, but I don’t loop chunks [of music]. I’ve never done that.

Who’s singing on “Natalia’s Song” then?

A Russian singer. I don’t know her name. I’m surprised [that song] doesn’t have like 2 million [YouTube] views. It’s really a work of art. I’m really proud of some of my tunes. The aim’s always been to make records that haven’t been realized–the dream songs between the great songs you can’t quite hear.

Well, now that you’re on a new label, some people who don’t keep up with electronic music will probably hear it now.

I hope so; I really do. I think a lot of kids are stuck with reading . [Laughs] They just think electronic music is kids in sportswear doing drugs. I’ll never be as famous as a drummer from a crap band.

It’s probably good you haven’t toured here much yet. People need to be ready for it.

I’ve been asked, but not been convinced it’d be worth it, honestly. I don’t do this for hipsters; I do this for all of us. I’m not into playing small vanity shows, but I’m not into being a arsehole either. I dunno; it’s hard to explain.

Well there’s a lot of kids here in Brooklyn that’d probably drop your name in a conversation but maybe don’t know the music that well.

That’s cool though. Not for the hype; just ‘cuz it’s cool to be known. I guess you guys are all Wolf Gang mad; French Montana probably only in the hood. Not sure Diplo and them listen to that shit.

I know you didn’t write the album with your dad in mind, but did you sequence it to tell a story of sorts?

In a sense, yeah. The album has its own narrative. I love to approach songs like that–picked on [their] own values, but together they have a new value.

Right, they’re separate stories that somehow converge; like a Tarantino movie or something.

Exactly. ‘Cuz it’s my experience articulating back at me–like looking in a mirror in a mirror. Not converge; whats the word? Convex? Fuck knows.

Is your music influenced by films or books at all?

I’ve not sat still for about 18 months. Before that, I read a lot; watched a lot of movies. I read deep shit, though, and watched heavy movies. I watched the other night, actually. I went on a Mike Leigh bender; I watched Naked also:I went into shock over my dad. I wasn’t ready for that. I lived off adrenaline for about six months.

Did it happen suddenly? Or was it more protracted?

He was fine, then one day he had some stomach pain, went to the doctor, and was in the hospital diagnosed with [metastatic kidney cancer]. Four months later, he died. He came home. I sat with him through it, making sure he was as good as he could be:There’s nothing you can do. You lose your mind.

Is that the first time you experienced something like that firsthand?

Yeah, I thought we were all gonna live forever. I was in a dream world– never broke a bone in my body; never saw my dad ill; never took a day off work. It sounds stupid now, but that’s life, isn’t it? You think you’re going to live forever:Life is alive. You can’t control it. You just make the best of it. [Laughs] I don’t mean that in a dark way. In a sense, it’s all meaningless, ‘cuz every moment your senses are awake and it’s all happening…You make choices; roll with it in a sense, I guess, or stand vehemently for what you believe in. [We’re all] prickles and goo, really.