The following exclusive feature was originally published in 2009. We’re running it in full this week as a tribute to Genesis P-Orridge, who passed away from a long battle with leukemia last Saturday.

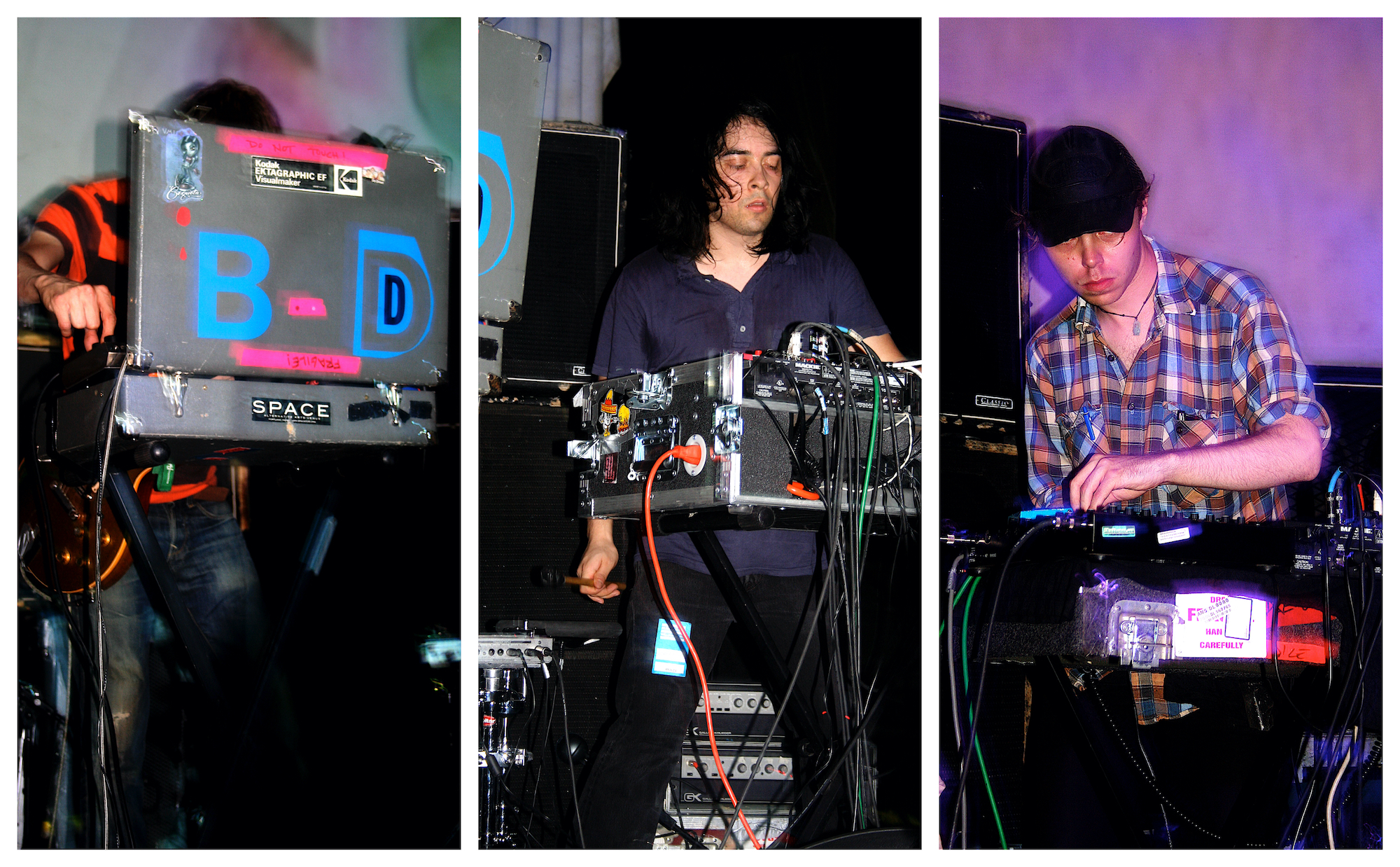

Photography LLOYD BISHOP

Interview ALAN LICHT

“Here it is,” wrote Alan Licht — a widely-respected experimental musician in his own right — as he delivered his unedited interview with Genesis P-Orridge and Black Dice, “All 68 pages/23,000 words of it.”

It goes without saying that such a sprawling Q&A far exceeded our expectations for a chance meeting between Brooklyn’s reigning noise-rock band and the legendary frontwoman of Psychic TV and Throbbing Gristle. To be honest, we were worried it would ever get off the ground at all. You see, things were awkward at first, as everyone met up at P-Orridge’s Queens apartment for a quick photo session and glasses of Raki, an anise-flavored liquor brought back from Turkey by P-Orridge’s daughter. It’s not that Black Dice’s three members (Aaron Warren, brothers Eric and Bjorn Copeland) were sitting in lock-jawed awe of an icon that greatly influenced the experimental scene they now inhabit.

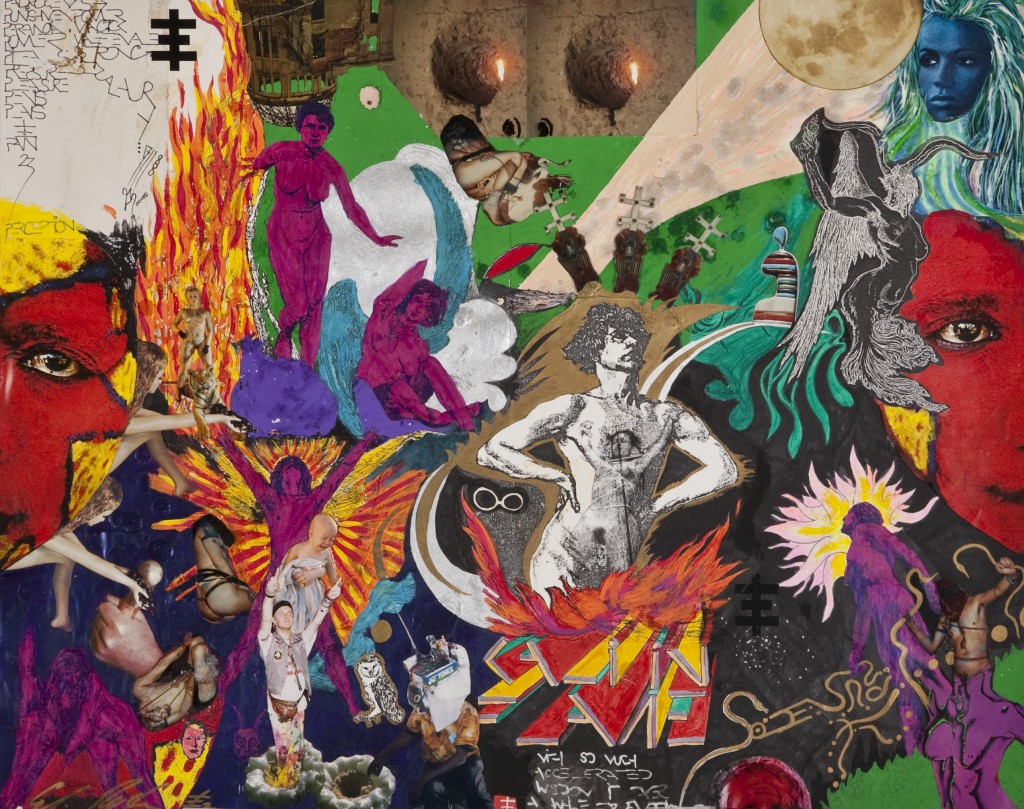

Okay, maybe they were; which would explain why no one could talk about anything but P-Orridge’s pudgy dog, Big Boy. For the first 15 minutes, at least. Then something happened, right around the time P-Orridge shared the original, framed “indecent collaged Queen postcards” that pissed off England’s royal highness more than any Sex Pistols song ever could. Standing here, amid African idols and the meaning-infused ephemera of lost counter-cultural eras, Black Dice and P-Orridge quickly realized what they share in common beyond music – a drive to create boundary-breaking, button-pushing art.

self-titled left the pair and Licht to their own devices at this point, only to find out that everyone ended up talking well until midnight – a good four hours in total. Normally, we’d cut huge chunks of an interview that’s as massive as the one you’re about to read. The problem with that is the loose conversational tone that P-Orridge and Black Dice kept throughout. Frankly, we feel this is one of the most thorough, and insightful, interviews we’ve ever seen with either artist….

Aaron Warren: I have a question to start things off: When we practice or tour, we listen to a lot of FM radio. Some of my favorite stuff is from the UK in the ’70s — [things like] ELO and 10cc. And I’m always like, “If I was a cool dude living in England in the ’70s, would I like this stuff or would I think it’s absolute shit?” Cause you know, I fancy myself something of a cool dude now [laughter], and I think it’s pretty good, but there’s a lot of stuff now that I feel is the equivalent of those bands, that I just cannot get behind. So I was wondering if….

Genesis P-Orridge: Having been in England in the ’70s, what did we think?

Aaron: Yeah.

Genesis: We wanted to like 10cc, cause it used to be the Hollies.

Aaron: Really? I didn’t know that.

Genesis: Yeah, the last remnants of the Hollies, who used to work in a boutique called the Toggery, which is where I used to buy mod clothes [laughs]. The production values were what I admired; the actual end result was kind of boring. It’s a bit like what Elton John’s like now. He just became all production and trickery.

Aaron: Phil Collins still makes me feel a little bit queasy when I hear him, but we have friends who say, ‘Oh, I love Genesis!’ Were there things from back then….

Genesis: You’re asking the wrong person [laughter]. The reason we started [Throbbing Gristle] was we couldn’t bear anything that was in the record shops at all. So we started doing our music out of frustration in ’75. And before that we were listening mainly to American music–the Velvets and stuff like that. The interesting British bands kind of petered out around ’71, when prog-rock happened.

Aaron: Were you behind something like ’70s-era Pink Floyd?

Genesis: No. To this day, we’ve never even listened to Dark Side of the Moon. Ever. [Laughter]

Bjorn Copeland: I guess I find there’s not too many things I like 100-percent, you know what I mean? If you took your favorite piece of artwork hanging in here and zoomed in, I’m sure there’d be things that would be decisions you wouldn’t have made. I feel like the flip side of that is there’s always something good in total dog shit. Nowadays, you’re exposed to so much stuff that I kinda feel like you have to get off on little details of some terrible song.

Genesis: That’s a very honorable attempt. We praise you for that, but we’re not interested in it at all [laughter]. We’ve got a really simple system which is that basically hardly anything in this house was made after 1969, and we were doing that with furniture, too, up ’til [Lady] Jaye [Breyer P-Orridge] passed. [Ed. note: Genesis’ longtime life partner/creative collaborator died of heart failure in the couple’s home on October 11, 2007.]

We were reducing everything down to just before 1970 – unless we made it. Because I think everything became really sophisticated around ’71, ’72. It was all based on the money thing. Brian Jones was murdered in ’69 because he couldn’t go to America with the Stones. And that was when Allen Klein came over, he took over the Beatles and the Stones, and basically was aware of – and made other people aware of – the fact that there was a huge amount of money to be made in the United States. And the Yardbirds became Led Zeppelin.

Aaron: See, I have a hard time imagining that there’s money to be made in the U.S. on music.

Genesis: And the Who went into Tommy. Suddenly they all shifted to looking at what America wanted.

Alan Licht: All those festivals too, was when people started realizing there was money to be made, like the Woodstock movie.

Bjorn: It’s funny, cause that whole phenomenon pretty much stopped after ’69 in the US.

Genesis: It died because the same people took over the stadiums and made stadium rock the thing —cut the legs out from underneath the free festivals. It was basically a money thing. [William] Burroughs always said, “When you want to know what’s really happening, look for the vested interests. Follow the money.”

People sold out, in the real sense. Not that they became popular, but that they made compromises because they wanted to make lots of money in America. British groups basically ignored Britain after ’72. And that left just the people who were trying to have hit records. But then you had the new underground by ’75. Cabaret Voltaire, and us, and punk. It went into do-it-yourself.

Aaron: The gear that you were using, was it expensive, or was it cheap?

Genesis: It was free [laughs]. The bass guitar that we used was left behind by somebody in our basement. [It] didn’t have strings, didn’t have pickups, so we bought two humbucker pickups and stuck ’em in. We didn’t realize they were meant for lead guitars. Chris [Carter] built his own synthesizer out of modules that he saw in electrician magazines. Sleazy just used some Walkmen and Sony tape decks. And Cosey [Fanni Tutti] bought her guitar at Woolworths for 15 pounds. We made our own speaker cabinets. It was as cheap as it could be.

Aaron: There’s something cool about having that direct a relationship with the shit you’re making sounds out of. It’s not something where you have to learn some other person’s vision, like scroll through menus and acquiesce.

Genesis: We made our own effects pedals, the Gristleizer, as well.

Aaron: What was the Gristleizer?

Genesis: It was some circuits that Chris found in a magazine that they said would be good for distortion, and built one each for us, the whole TG sound is those.

Aaron: Do you have that kind of gear still?

Genesis: My Gristleizer was burned to death in L.A. in ’95, sadly. Sleazy’s just stopped working and couldn’t be repaired, cause now they don’t make the same parts. He tried to make a new one and it just didn’t sound the same. So they’re all gone, from wear and tear, we don’t have ’em anymore.

Alan: [To Black Dice] Do you guys build your own gear at all?

Bjorn: We had stuff built before. Our old drummer Hisham [Bharoocha] was working at Electro Harmonix and a guy there built us a pre-amp pedal, and then our friend Gavin Russom built me a briefcase that has like two filters and a 10-step sequencer that we used for a long time, but it’s really nerve-wracking. I don’t know how to fix that shit myself, so every time we would go on tour there would be a couple of really sketchy moments.

Aaron: When I started playing with these dudes, I had nothing. [I] just borrowed stuff from everyone. But now I don’t go that route. My current philosophy is I go to Guitar Center [and get] brand new [equipment]. If it breaks, I just get another one, and I can get a sound out of that.

Genesis: We were lucky. Sleazy and Chris, to this day, are really into soldering irons and fiddling with electronics. When Walkmens first came out, Sleazy bought six, cause he was over in Japan doing a photo shoot for somebody, and brought them back. And then he got inside them and customized them himself, so he could play both sides of the cassette tape at the same time.

Aaron: Oh, sweet.

Genesis: And then he put them through a keyboard, re-routing everything so that each key played one side of the tape. So you’d have 12 sounds coming through 12 keys, and that meant he could record anything he wanted on the cassettes. He could play them as if it were a keyboard, or he could sequence the keyboard too, make rhythms with them. He had infinite options of what was on the tape.

“That was the one where

there was a big riot,

where they were throwing toilets

and things at us.”

Bjorn: Wolf Eyes are the only people I know who are capable of that stuff nowadays.

Aaron: Nate [Young]’s doing beautiful pedals that are sort of like art projects. There’s this one that comes with a cassette, plays a tone, and then you press this button–it’s like what you’re talking about.

Genesis: We used to have TV aerials on the PA system and be able to pick up random TV broadcasts. Sometimes we’d even get news programs coming through. People would think they were samples or loops, and then go home and find out they’d really heard what was happening that day while they were at the gig. It was really a precursor of samplers. There was the Mellotron, in the ’60s, which is what the Beatles play on “Strawberry Fields.”

Bjorn: And the Optigons; did you ever play on one of those? Kind of similar but it plays on an acetate, and reads it optically. They’re cool cause you can cut ’em up, stack ’em, flip ’em over and it’ll play it backwards.

Genesis: Oh, no, I’ve never heard of those. We were just trying to apply the Burroughs idea of cut-ups into the music. John Cage, Burroughs — what happens when they all collide. That was one reason we didn’t want to have a drummer; we didn’t want it to be sidetracked because most drummers go into particular rhythmic patterns, and then you’re stuck.

Aaron: [Laughs] I agree. [Laughter]

Genesis: And at that time, we wanted to be just absolutely separate from any sort of normal rock ‘n’ roll.

Bjorn: But the presentation and vibe of it seemed very much to be rock. I mean, it had a rebellious quality, it had a sexiness to it — traits that people have historically attributed to rock music, and now probably attribute to hip hop.

Genesis: Well, we thought of it as an anti-rock band. We tried everything we could think of to confound the audience’s expectations of what a band was. We did one gig – maybe the third or fourth gig – where we had all these mylar mirrors across the front of the stage. We were behind them, so the audience could only see themselves the whole time.

And another one we played inside a scaffolding box in a courtyard, at the Architectural Association, and we had the cameras inside so if you wanted to see us play you had to walk round the building and look at the monitors, but you couldn’t hear anything. Or you had to go on the roof and lean out the windows and look down to hear it.

That was the one where there was a big riot, where they were throwing toilets and things at us. Thank god we built that box strong [laughter], ’cause they could have killed us otherwise.

Aaron: Did you play in pubs or regular rock clubs? ‘Cause with a lot of our shows – even now, but especially early on – we’ll be playing a sports bar, and it’s terrifying ’cause you think the dude behind the bar is going to kill you during your set.

Genesis: We did the Nag’s Head in High Wycombe; that was one of the first. Everything went wrong with our homemade equipment that night, so while they were trying to fix everything, I jumped onto the tables where people were sitting and drinking their beer, hoping they’d be too scared of me being insane to do anything about it. There weren’t that many people there, but they didn’t do anything.

The writeup said, ‘Even an ape with seven arms could play music better than this.’

Bjorn: We had a lot of times where people turned the power off. We definitely got beat up while playing, [or] people [threw] bottles.

Genesis: Why don’t they just leave? That’s what I always wanted to know, why don’t they just go away?

Bjorn: Everybody would like it if what they were doing was widely embraced but sometimes there’s something really satisfying about being able to provoke people to certain extremes like that, you know?

Alan: Dee Pop, the drummer for the Bush Tetras, had this great story I saw somewhere, about going to see the Ramones at CBGB. Someone dragged him there, and he hated them; he thought it was the worst show he’d ever seen. Then he went back to see them the next night [laughs]. Not even going to give it a second chance, but because he hated it so much. I think there’s something to that, being attracted to something you feel diametrically opposed to.

Bjorn: That’s the American Way right now, man. If you look at what’s programmed on television, you’re watching shit that just makes you feel ill – Cops, watching poor people get fuckin’ busted, or Wife Swap or….

Aaron: Dude, TMZ!

Bjorn: Yeah, there’s so much about misfortune, and I think that people really get off on that. But I think when people go see live music, people feel entitled in a way, that they deserve to get what they expected. Which is difficult if you’re a band that’s always tried to discredit that.

Genesis: It didn’t used to be like that.

Bjorn: You don’t think so?

Genesis: No. When we saw people like Pink Floyd with Syd Barrett, we were really excited when it wasn’t what we expected. We wanted to go and see something novel, something different, see them create sounds we’d never, ever heard before. And when we liked Captain Beefheart at the beginning, he was doing pretty straightforward, bluesy rip-offs, and then within a couple of years he was doing Trout Mask Replica. We’d all sit around and be excited because we were sort of befuddled by how far he’d stretched it. We didn’t think he’s let us down because he didn’t do what we thought he was gonna do. And we wouldn’t shout at people if they did something different when we saw them live.

Bjorn: I think it’s a really young attitude. You go through certain periods, certain ages where you feel like your identity is so attached to what music you like, and you outgrow it pretty quickly.

Genesis: I guess the one time it was a little different was Marc Bolan — when he went electric, and came ’round to our university. There were only four or five people there. One was me, and my friend, and it was brilliant. There was this great big hall in this university, and there was five of us, stoned out of our heads [laughter]. He did a couple of little songs, and then he plugged in his amp, really turned it up loud, and did a 40-minute guitar solo, it was amazing!

Aaron: Was it loud?

Genesis: Yeah, it was great!

AL: Was he just by himself?

Genesis: Yeah, just him.

Eric: Was that stuff an anomaly for the time, or an anomaly for you and your friends?

Genesis: Well, people would just stay away if they heard it’d changed in a way that they wouldn’t want to hear. They wouldn’t go along and complain about it. We’ve had people turn up at gigs and buy tickets for $30, knowing they just want to heckle. Which to me is just, beyond comprehension. To spend an evening to go and not be happy – why? Why? It’s much more common in America for people to feel aggressive towards bands that they feel have somehow let them down.

Bjorn: You know, I feel like it’s the exact opposite. some soccer bloke in England….

Aaron: In England they love to tell you what sucked about your set in a way that no one would ever dare do in America.

Bjorn: The first tour we did without a drummer, the show sucked basically. We played okay, but the trains had fuckin stopped, the opening bands had played forever…. So we played the show, and some fucking asshole comes up and goes, ‘Where’s your fucking drummer? You need your drummer; it sucks without the drummer.’

Genesis: No, you’re right, when we said Europe, we weren’t including England [laughter]. You’re right; the English can be real bastards.

Bjorn: Germany too…. When we started, people were real antagonistic about it. When we would play other places, they would call us faggots and stuff like that before we even played. So I think we developed this sort of thick skin and pride that we knew it was better than the audience, you know what I mean?

Genesis: You have to do that. We did that with TG as well.

Bjorn: We’ve sort of grown up with a bunch of different bands at this point and I feel like we’re completely different in the fact that we never wanted to be friends with everybody in the audience…. It is sort of this backwards logic that I feel we’ve used the whole time.

“That’s the main dynamic—

like jerking off to porn

isn’t the same as a lover”

Genesis: Do you think there’s been a change because of the Internet, and the more global accessibility of things? What’s the difference between the late ’60s and early ’70s, when people had to make an effort to find out what a band were like? In Britain and most of Europe, there were just a couple of government radio stations that were very controlled; they closed down the pirates.

So you had music press that would tell you about stuff, or you had to go and see it. There was nothing else; you couldn’t go online and download things, or find out a thousand other people’s opinions. Do you think that’s changing the way that bands interact with audiences, that audiences are changing their way of absorbing music?

Eric Copeland: I think it’s almost too early to ask…. The internet, for me, is something that’s still discovering what it’s capable of. I think it’s a valid question, but I almost feel like we’re in the middle of a transformation that will not transform you or me, but anybody who grew up with it. That will be the ultimate transformation in the planet.

Genesis: Do you think it matters whether young people know the story of their own music? The way it’s evolved and progressed from the ’50s through now? Do you think it makes any difference to them to know the roots of their music?

Aaron: I don’t think it matters.

Eric: Part of me feels like, if you just get caught up in the history of stuff, then you kinda hit the brakes at points too. I personally like reading about history, and seeing this constant smear instead of these isolated things, but at the same time, I feel like ultimately that information becomes disposable:

Genesis: Well, here’s an example: What about if people who like Interpol were told to sit down and listen to Joy Division? Would they have a different view of Interpol?

Eric: The Internet becomes this communal brain. I don’t know if it matters if I have all that information, or if I can use that information.

Aaron: One of the things about the Internet is it kind of gets rid of that linear, timeline-based kinda shit, where it’s like, Joy Division was first, so they’re more authentic and they’re better.

Genesis: I wasn’t thinking of it so much as they’re better in any way, just that… sometimes people are surviving on other people’s ignorance.

Aaron:Everything exists kind of on the same level, where it’s all equally available to you — all the information, all the music. It’s gonna be interesting to see how that pans out, because the way that we grew up, we had a hierarchy of available media to us. There’s shit that was free to us, and there’s shit that we had to seek out.

That’s been blown away now; everything’s just kind of on the surface. It just depends on how much free time you have, and how interested you are in it.

In addition, you are able to comment on it and become a sort of critic as a listener. Your opinion is equally valid. It kind of gets to that thing you were talking about — where you play a show and someone feels like they can you just tell you what they thought of it, and you’re supposed to fucking care. That’s sort of where we’re at, where these kids are reviewing your record the instant it’s on. I sucks in a way, but in another way, I think it’s kinda great too.

Genesis: In 1966, we would have to save up money secretly by selling drugs, and then hitchhike to London, and then go around Soho that night looking for a porno shop that might have a William Burroughs book in it by mistake, and then buy that book. But in that journey, we’d find people who would let us sleep on their floor. We’d talk to them about what they did or where they’d been, and maybe make friends with them. We’d find all these other places we’d never knew existed, or we’d meet people while we were hitchhiking and we’d hear their stories.

Do you think it’s the same journey on the Internet?

Eric: Part of me feels like, no way, you can’t trade any sort of experience for…. You know, if you go to YouTube, all these recommendations come up when you’re done watching a clip. Depending on my mood, I put value on that or [I don’t]. Sometimes I’m willing to just be like, ‘This is the journey; ‘I’ll be on some Japanese sex site in two clicks, but at the same time it won’t be like hitchhiking.

Alan: It will lead you to things.

Genesis: YouTube is definitely one of the most dynamic forums, don’t you think?

Aaron: Social networking is something that’s for a younger generation than any of us. I’m personally not interested in talking to anybody on the internet that I don’t know. But if you’ve grown up with that, you’re totally comfortable with it. If you’re searching out some William Burroughs shit, you might also meet someone across the world whose interested in that and you can forge a real relationship with that person.

Genesis: But you wouldn’t have met them if you had to go physically there.

Aaron: Yeah, you would have never encountered them at all. That’s some shit that I don’t take advantage of ’cause it’s too foreign a concept to me.

Eric: It seems really obvious but the internet’s not a physical relationship. To me that’s the main dynamic — like [how] jerking off to porn isn’t the same as a lover.

Bjorn: I feel like everybody finds out about shit at their own rate. It’s kind of similar to why the whole school system sucks because you’re forced to look at things that you need to know but don’t have any interest in at the time. After I finished school, I felt like I definitely wouldn’t have slept through every art history lecture in retrospect.

Genesis: Did you all go to RISD?

Bjorn: Eric almost did. We started playing when he was in high school.

Genesis: You’re from Rhode Island?

Eric: No, I’m from Maine; Aaron and I both went to school in the city.

Genesis: Where did you go?

Aaron: NYU.

Genesis: What did you study?

Aaron: I studied film; Eric studied religion.

Eric:I studied, like, the Bible.

Genesis: Really?

Eric: It took me three years to realize I didn’t want to be a Bible scholar, but I got the education that I lacked. And I actually follow those ideas a little more now. It was a good foundation.

Genesis [to Bjorn]: And what about you?

Bjorn: I studied sculpture, which is why I’m broke as shit and always on the verge of eviction [laughs]. [Rhode Island] was where we started; there was a lot of really energetic, fucked up bands. It was interesting ’cause no bands would come to Providence and play, but we saw some really amazing, encouraging shows just through our friends.

Genesis: When we started TG there were the Cabs, and SPK, and Clock DVA:

Bjorn: Were Esplendor Geometrico around yet?

Genesis: They came a little bit later, but we had that little network. We didn’t even play the same style, but we put each other on shows as support bands. Did you have a little coterie of friends, or bands that started out at the same sort of time as you?

Aaron: Yeah, for sure.

Bjorn: They’re all bigger than us now though [laughter].

Genesis: Who are they?

Bjorn: Lightning Bolt was the band we did our first tour with. They’re amazing at what they do.

Eric: They’re like superheroes.

Bjorn: They’re super-DIY, the aesthetic is really Gary Panter — sort of tripped-out cartoon stuff and they’re both…

Aaron: Virtuosos.

Bjorn: Yeah, they’re sort of like throwback musicians in that way. I don’t really like Rush and shit like that, but in my head I like the idea of superhero musicians and what that represents to a kid. I don’t like KISS, but I could see why if I was 0 or 11 why that would seem like the coolest band. Lightning Bolt serves all of those purposes.

We’ve been extremely fortunate. [Lightning Bolt] was one of the first bands that we played with — [them] and Wolf Eyes, Animal Collective, Gang Gang Dance. It made it a lot easier to tour to have a couple of friends around when you knew the audience was going to fucking hate you at like 99-percent of the shows.

Genesis: Have you seen a change in the way gigs are organized?

Aaron: Sure. Even with the kind of tour that we’re interested in doing right now, we have a pro booking agent but we’re actively always trying to find the least pro places to do the shows. It doesn’t make any sense in a way because it’s totally against our interest. We need the money to do the tour, but at the same time we need to have a tour we think we can live with.

Genesis: [Like] that one [at Market Hotel in Brooklyn] where Gibby [Haynes] was DJing.

Aaron: Yeah, totally.

Bjorn: The tools have changed…With the Iinternet, I feel like we’ve seen the first wave of bands that got really popular based off a MySpace page.

Genesis: Like Arctic Monkeys.

Bjorn: Like Arctic Monkeys, Clap Your Hands Say Yeah, Lily Allen — all these things. I just don’t know how long that stuff can really stay around. It’s fantastic to do something that people can connect with, but if it’s at the cost of your ability to grow as a person or as an artist, it sounds like a bad idea. And at this point there aren’t that many bands that are around for over a decade.

Genesis: That’s another question we’ve been curious about: longevity. Things surge upwards really fast in this environment, and they also disappear really fast as well. They seem highly disposable on every side. And that’s accelerated incredibly; people would find a band and be loyal to it, and watch it grow into different albums — see them get more experimental, more melodic or whatever. Now that seems quite unusual.

Alan: I think you’re right that it’s accelerated, although that’s always been the case [with pop music]. A lot of people are just one-hit wonders:

Bjorn: Yeah, there’s that cycle of something else always coming up. The internet certainly accelerates it, in that you don’t have to wait three months to find out what band sounds like the Arctic Monkeys. You can find out instantly.

Genesis: So, in 20 years, will there be as many people listening to the Arctic Monkeys as [there] were the Beatles 20 years later? I just wonder what the longevity of the music itself really is. At the moment, with all these different things happening, and the major labels, they’re really falling apart.

Bjorn: Yeah, we did a stint on EMI and it was… a humbling affair.

Genesis: Yeah, we had a couple of terrible experiences with major labels as well.

Bjorn: It made us sort of feel like idiots. Everyone who had put out records by us in the past liked us for specific reasons that they could articulate to us, and with them, we knew they had no idea.

Genesis: Are we seeing the end of music having any sort of global appeal? Is it going to become lots of little tiny islands that just float to the top and then sink away?

Eric: But why do they have to sink away if…

Genesis: In terms of attention from people, that’s all.

EC: But that’s the thing…me continuing to make music doesn’t require an audience, except in this idea of being a band, where if people don’t like you, you can’t be a band [laughter].

Aaron: No one told us that [laughs].

Genesis: We’ve never relied on music to make a living, because we knew we couldn’t [laughs].

Eric: Except you’re playing Coachella.

Genesis: That’s a fucking weird thing, isn’t it? After 35 years [laughter]. If you take that fee and spread it out over 35 years, it’s not much, is it?

Aaron: When did TG break up?

Genesis: TG broke up in 81.

Bjorn: And that was in LA, or San Francisco?

Genesis: [Laughs] There are different versions of this story, so: this is just my personal version, which has one person who agrees with it: Monte Cazazza. We were walking to this radio station prior to the LA gig, and I said to Monte, “I’m not going to do this anymore after these two gigs.” I said I’m going to tell them on the radio. So when the guy says on the radio, “So what’s in the future for Throbbing Gristle?” I piped up and said, “Nothing.” [Laughter] Three people turned around and went [makes face; everyone laughs]. And there’s a photo of that, with Monte behind this window, laughing his head off [laughter].

Bjorn: What’s funny is when I read about Throbbing Gristle gigs in that book Wreckers of Civilisation, which is a dense motherfucking read…

Genesis: It’s a good read.

Bjorn: It is a good read, but there’s a lot of fucking information in there. The amount of records you guys were selling was substantial by American independent standards.

Aaron: Especially modern standards.

Bjorn: And the size of the gigs too — at least the LA venues — that’s like indie gold, from that time up to the ’90s, really.

Genesis: I don’t think we ever got more than a thousand dollars for a gig. And that was probably just the last two.

Eric: I bet it could be as low as 20 quid or something like that [laughter].

Genesis: It was–there were things that were just like 30 pounds or something.

Bjorn: We got paid in change many times, or cigarettes, and we don’t even smoke cigarettes.

Aaron: When I joined the band four years in or something, it was at least another four years [until we made $500 for a show].

Bjorn: I get totally pissed when we invite friends to play a gig with us and they get all heavy about money, or they bitch about stuff. I’m like, You motherfuckers, do you know how long it took us to get paid $100 to do a fuckin’ show?’ [Laughter]

Genesis: The only gigs we did outside of England were two, maybe three in Germany. Don’t remember what we got paid for those, but we got travel expenses plus a little bit, and slept on the floor of a warehouse.

Bjorn: We do that pretty regularly.

Genesis: And the two gigs in America. There were only five outside England.

Aaron: So you’ve only played two shows in America until this upcoming [short tour]? And you never played in New York? That’s wild.

Genesis: No, no, we just did LA and San Francisco.

Bjorn: That San Francisco show — did you identify at all with the bands that were playing?

Genesis: Well, I thought Flipper were great.

Bjorn: One of my good friends was tight bros with one of those guys, the dude that died….

Alan: Will Shatter.

Genesis: We met the Flipper people through Monte.

Eric: Didn’t Black Flag play that show?

Genesis: Black Flag did the LA one. And Don Bolles… after the Germs, after Darby died, Don Bolles started 45 Grave, and they played in LA as well.

Aaron: Shit, what was that venue?

Genesis: Veteran’s Auditorium, Culver City.

Aaron: Fuck, I used to live in Culver City.

Genesis: Uh, to me it was a disaster,. Something went wrong with the PA, and all I could hear was white noise and I just thought, ‘Fuck it.’ I just started banging the guitar and kicking it [laughs].

Bjorn: This is totally nerd shit, but did you guys go direct most of time, into the PA? I’ve seen pictures of you doing feedback off the monitors, so I figured it must be going through DI.

Genesis: What we mainly did by the second half of TG, we wanted to miniaturize…. It started as a joke. You know how the progressive groups had the biggest drum kit, and the biggest PAs and the biggest keyboards? We thought, ‘Let’s make everything as small as we can.’ So we each had just a flight case, and the lid had the pedals on it. There’d be a little tiny monitor in it, so you could hear what you’re doing, you had one Gristleizer, maybe a little echo thing, and you plugged into that. So when you set up, you just took the lid off, put it on the floor, plugged it in, sent the DI, and that was it.

Aaron: That’s awesome.

Eric: We could have learned that lesson a long time ago [laughter].

Aaron: Did you ever have any problems at airports? Nowadays that’s a real problem for us.

Genesis: No, they weren’t worried about it then. It just went on as normal luggage. Sometimes they opened it up and said, “What the hell’s that?”

Eri: They never made you play it at the airport? [Laughter] I remember Detroit, once, we had somebody say, ‘Sing for us.’

Aaron: That was right after 9/11.

Bjorn: If they ask you what it is and you just say, “I make beats with it,” that’s like layman’s terms [and] they’ll let you go through.

Genesis: It was much more fun to play when it was simplified like that.

Eric: Is it the same four people playing these Coachella shows as well?

Bjorn: And Sleazy does Coil?

Genesis: Not now, because Geoff [Rushton] died, so he’s now called SoiSong, and working with this — is it Danish? — guy. It’s just the two of them, all ambient, using two laptops.

Bjorn: We were asked to play the first RE-TG fest.

Aaron: The one that got cancelled.

Genesis: I know, that was such a mess.

Aaron: Yeah, we were bummed about that. We were really psyched.

Genesis: We were too. And when they finally got us there, they… it wasn’t much fun. Let’s just say that.

“A lot of them are

made up onstage”

Eric: I have a question for you: Do you play music every day?

Genesis: Me? No.

Eric: How often do you play then?

Genesis: Do you mean in the background?

Eric: No no, I mean how often do you just kind of sit around, and make music?

Genesis: Never.

Eric: When was the last time?

Genesis: The last gig.

EC: That’s fair. [Genesis laughs] Do you draw and make collages everyday?

Genesis: Oh yeah, pretty much. And write.

Eric: What do you write?

Genesis: Poems, essays, articles for magazines, books….

Alan: Lyrics?

Genesis: Yeah, when there’s songs to do…. A lot of the things in the notebooks — poems and ideas — turn into lyrics later. Or else I’ll say, ‘What shall I sing about today?’ [Laughs] That’s how “Discipline” happened. We were in Berlin, turned around before we went onstage, and said, “What shall I sing about, Sleazy?” And he goes, “Discipline.” I said, “Okay,” [laughter] and I went onstage and made it up on the spot. t worked; a lot of them are made up onstage.

Aaron: Have you had ones that…

Genesis: That don’t work? Oh yeah. Yeah [laughs]. But amazingly, a high number of them are okay.

Aaron: The good ones aren’t good unless you’ve had some bad ones, basically.

Genesis: You can’t cheat. You’re there in front of the audience and there’s all this energy funneling in… What we try is channeling — being lost in it, going into a trance. When we’re making up lyrics, it’s basically me describing a film in my head, and telling people what I’m seeing. That’s kind of how it works. When [Psychic TV] did “I.C. Water” — the one about Ian Curtis — we painted the wall gray, put the microphone right against it, and I faced this gray wall for about an hour, then said, I’m ready, and then sang it straight down on tape. And that was it – one take.

Aaron: Did you have [your own] studio setup?

Genesis: Second Annual Report was recorded on a Sony cassette.

Aaron: Something like this [points to Alan’s tape recorder]?

Genesis: Slightly bigger. In those days, they were bigger. Put it on a table in the back of the room, and that was it.

Aaron: That’s cool.

Genesis: And it’s never been out of print since.

EC: Who put it out?

Genesis: We did.

Eric: You guys have kept it in print the whole time?

Genesis: No, since then it’s been licensed to other people.

Aaron: You mean you took that cassette tape and you gave it to the record place and…

Genesis: Said, “Can you make this into an album, please?” [Laughter] It was Burroughs that suggested that.

Eric: All his stuff’s at this place that I work that has all that Psychic TV stuff. There’s a lot of Burroughs stuff being reissued right now–a lot of spoken word stuff.

Genesis: It’s not Nothing Here Now But the Recordings, is it?

EC: I don’t think so. I would describe the cover, but a black and white photo of William Burroughs probably describes most of them [laughter].

Aaron: I was just listening to 20 Jazz Funk Greats. You kind of had a more pro setup [for that one]?

Genesis: No, that was done on Paul McCartney’s. We borrowed his 16-track from Mull of Kintyre, his island. Sleazy’s other job was [designing] for Hipgnosis. He’d just done the Venus and Mars cover for Paul McCartney, so Paul was really happy with Sleazy. And Sleazy says, “My band’s looking for a better tape recorder,” and he goes, Oh, I have a 16-track at my farm, the Mull of Kintyre, you can borrow that if you want.”

So they shipped it down, and we dragged it into the basement in the Factory — our Death Factory — and it had mold, moss and stuff on it [laughter]. It really was from the farm. So we had to scrape it clean, but it worked.

Aaron: It’s got a good sound, that record.

Genesis: It’s that two-inch, 16-track tape.

Eric: But all that Psychic TV stuff–is that the same Sony recorder?

Genesis: Yes.

Bjorn: Really?

Eric: You got some mileage out of that.

Genesis: Once in a while it came through the mixer but we preferred it when it was just a cassette deck.

Aaron: Holy shit.

Bjorn: Wow.

Genesis: It just goes to prove that there’s something other than professional quality involved.

Bjorn: I feel like the professional standards are the ones that become dated the most quickly, that’s why I like everything that’s on the radio now, there’s a 100-percent guarantee you’re gonna hear an Auto-Tune on a vocal if you turn on hip-hop stations.

Alan: It’s like hit radio from the ’80s….

Genesis: When they used to use aural exciters. In the ’80s, Fleetwood Mac used them a lot. It was this weird effect that you could use in a studio and put all those [hisses] kind of high sounds in it. ELO used it as well. Everybody used it on the hit records. It was almost like a magical thing; it somehow made people really like it [laughter]. It had a strange effect, like a drug almost, where people felt attracted to things that had this hissy, high-pitched sound.

Ala: The thing about high end, also, is, I was reading about how massive cocaine use really damages your hearing so you can’t hear high frequencies as much. People who were engineering records back then had done so much cocaine that they would be in the studio and go, “I can’t hear any highs,” and they’d be pushing it up in the mix.

Genesis: Oh, is that where it came from, the aural exciter? So should we call it the cocaine exciter? [Laughter] We tried it; it didn’t seem to make any difference to us.

Bjorn: We tried to use an Auto-Tuner, and Nicolas [Vernhes], the guy we were recording with, was like, “Fuck you.” [Laughter]

Genesis: Like on that Cher record (“Believe”)?

Bjorn: [That] was the big one — the best use of it, too.

Genesis: Yeah, that was new. Even we went, “Wow.” But whatever happened to holophonic sound? Dreams Less Sweet is still the only album in the world that was completely holophonic.

Eric: What’s holophonic?

Genesis: Dimensional sound.

Eric: When did that come about?

Genesis: We recorded that in ’83. This guy Hugo Zuccarelli invented this special new way of recording sound. Part of it was a real human skull, with latex skin and real human hair, called “Ringo” cause it was the skull of a Mexican boxer called Ringo who died in the ring. Which is… interesting. Not really useful to the sound, [laughter] but he had little bags of liquid where the inner ear is, so he tried to construct as near as he could an entire person’s head with a sack of liquid for the brain, and so on. And right in the center of that was something, which he wouldn’t tell, and he hid the papers all over the world, which went through a wire and into a black box. And in the black box, the digital information from this whatever, was changed back into code that could become sound again.

Eric: Analog?

Genesis: No, this was digital. Three-dimensional digital — the first time ever it had been done. Pink Floyd used it on Meddle, maybe?

Eric: Did you need a special player to understand this?

Genesis: Oh yeah, when we used it, Sony brought an entire mobile studio they built specifically for it, and the tape was circular but twice this diameter.

Aaron: Bullshit! [Laughter]

Genesis: And it was only this thick; it was really strange.

Aaron: That has gotta be mega-expensive.

Genesis: Well, they did it for free, because they’d been trying to get people to do it on a whole album and no one else would. Pink Floyd used it for sound effects only, and Michael Jackson used it on Thriller but only for the sound effects, and we said we’ll use [it] for the whole fucking album. So they created this whole studio for us, at this place called Jacob’s.

We tried all these things — we put it in a coffin and buried it, so you can hear yourself being buried alive on the record. And we got this guy from a film studio to come with a license and fire guns past its ears so you could hear bullets flying past… all kinds of stuff. We did a tattoo on it [laughter]. We got clippers and pretended to cut its hair. We put it on a rope and swung him so he was flying around the studio while we played live so it was recording wherever it went.

Eric: And what happened to all this?

Genesis: It was released as an album on CBS.

Eric: On CBS. [Laughter] What type of dude are you dealing with where you can propose all this shit and he’s cool with it?

Genesis: Muff Winwood, Stevie Winwood’s brother.

Aaron: Ah shit, really?

Genesis: Well, the intermediary was Stev-o, at Some Bizarre, who had this momen in the ’80s of being really hot because he had Soft Cell. He released “Tainted Love” and got loads of money from that. So all these major labels thought he’s got his finger on the pulse. So he got Einstürzende [Neubaten] a major deal, he got us a deal, he got the Cabs a deal. He had golden fingers for about two years. And that’s how we could afford to do this thing.

Aaron: Was everyone doing a high budget record?

Genesis: High budget weird record. It was very funny, we went into the Hell Fire Club caves, because Zuccarelli reckoned it would pick up atmosphere as well; we recorded in the place where Aleister Crowley did his Rites of Eleusis and gave out magic mushrooms; we recorded in a church with an opera singer. This choir, they were actually singing Craft Ebbing’s “Psychopathia Sexualis,” so if you translated the Latin it was actually about a woman who had a perversion about young boys. It was wild; we couldn’t believe our luck. And the more ridiculous the things we suggested, the more they’d go, “Yeah, that sounds great, we’ll organize it for you [laughter].”

Eric: What was their reaction?

Aaron: Was there a fallout afterwards?

Genesis: No, no they liked it a lot. The fallout came [laughter] when we said we wanted to release “Godstar” as a single.

Aaron: But you did release that as a single.

Genesis: On our own label. Muff Winwood said, “I don’t like it, it will never be a hit, why can’t you do something more like that other one, Dreams Less Sweet?” We said, “Well, we think this is a really good song… Muff Winwood, you couldn’t sell records if you were a fucking chimpanzee, we’re not on your label anymore,” and walked out. Went and formed my own label and released it and it was number one in the indie charts for 15 weeks.

Aaron: That was a huge record.

Genesis: Went into the national charts as well. He was wrong! Fucking idiot.

Eric: Did you ever hear the Television Personalities version?

Genesis: Oh yes – because we met them on tour.

Eric: That was how I heard that song.

Genesis: They told us they did it, but I haven’t heard that. [Sings] “This is a story, a very special story, it’s about Brian Jones, one of the Rolling Sto-oo-ones.” [Laughs] What a great intro. That came out onstage, I made it up onstage…. We played the Hacienda, and Alex Fergusson suddenly went da-da-dunh, that sort of Keith Richards-y thing. And I’d been thinking about Brian Jones, I’d read a book about him, so that was my subject, and I just sang this fucking song.

Afterward everyone goes, “Oh, what was that new song? The one about Brian Jones?” “Oh I don’t know, I don’t remember what I said.” So then we were all scrambling around before people left the venue, “Did anybody record that?” [Laughter] Luckily we found someone who had a tape, and then I took it home and I transcribed what I’d sung. I didn’t remember singing it at all.

Eric: What about the cover of “Are You Experienced?”

Genesis: With Caresse, my daughter? Isn’t it great?

Bjorn: Oh my god, she’s gorgeous. It’s an 8-year-old girl singing, and she’s dressed up like an Indian or something like that:

Genesis: And she pretends to take a tab of acid and put it on her tongue. It’s slowed down; it’s the Quaalude version [laughs]. That ended up being the theme music for an Italian pop music show for about two years. She was a big star in Italy [laughter].

Bjorn: How much shit did you get for….

Genesis: Oh, we got shit for that, yeah.

Aaron: Did that ever come down to legal crap though?

Genesis: They threw that into the mix when they chucked us out of England, it was all sort of… innuendo.

Aaron: Where did you have to go when you got…

Genesis: I was already in Katmandu. I got a phone call saying, “You can’t come back [laughs].”

Eric: I figured you would have had the customs agent going, “Nope.” [Laughter]

Genesis: The thing that’s ironic is we were in Katmandu using our PTV royalties – from “Godstar,” funnily enough. We felt guilty about making money [laughs]. So we went there through these Tibetan Buddhist monks we knew, and we financed a soup kitchen all through the winter, for the refugees from Tibet, and lepers and beggars and little children that were orphans. We fed them three times a day – sometimes 3 or 400 people. We got all our fans to send clothing, so they could keep warm. And it was while we were doing that we were told we were the most evil people in Britain and couldn’t come back [laughs].

I was sitting on the bed thinking, what do I do now? And my eyes caught this envelope with all these old letters in it. As we were leaving the house to go away, I just put all the mail in an envelope and put it in a bag. So I started going through [it] ’cause I was kind of in shock, and there’s one there from Michael Horowitz. So we open it, and inside there’s a postcard, which says, “We were at the gig at Dingwall’s, and it was the most psychedelic thing we’ve seen since the Acid Tests in 1966. If you ever need a refuge, call this number.”

We went back into the town, because there was only one place you could phone outside, phoned up Michael and said we need a refuge, me and the kids. And he goes, “Okay, can you get to San Francisco? If you can get here, we’ll pick you up, you can stay with us.” Then I rang Wax Trax!, and said, “I need tickets for me and the kids, one way to America, could you front the money?” They said okay. So that’s how we got here. And Michael Horowitz is the person who hid Timothy Leary’s archive when he was in jail, and also is Winona Ryder’s dad…. Her parents let us stay in her old bedroom.

Aaron: That’s fuckin’ wild.

Genesis: And then, because we were staying there, Timothy Leary rang up and said, “Why don’t you come and visit me in LA? I’ve got a car in their back garden, you can have that.” We looked and there was an old Honda, and the license plate said “Hi-Orbit”. We got that fixed so it would run, and drove it down to LA, stayed with him for a while, and started doing these events with him. We did all the video and sound for “How To Operate Your Brain” for him.

Bjorn: Oh really? I love that clip that was on YouTube. Were you interested in what he was talking about as practitioners?

Genesis: You mean were we psychedelicized [laughter]? Yes, we were, absolutely — and continue to be to this day [laughter].

Bjorn: Were bands like AMM influential to you?

Genesis: Oh yeah, definitely. Cornelius Cardew. And the early Soft Machine was interesting.

Aaron: The first Soft Machine is the best fucking record ever.

Bjorn: Yeah, the first one is badass.

Genesis: You know about it?! Alright! Isn’t it great?

Aaron: I listen to that record once a month. It’s so good. If I listen to one song, I have to listen to the whole thing.

Bjorn: They don’t stay that good though; they get sort of jazzy.

Genesis: How many people would know about them over here? Well done, you lot. Fancy that being a point of commonality! [Laughter]

Bjorn: That Robert Wyatt solo stuff is gorgeous. I mean, it’s depressing as hell, but….

Genesis: There’s a couple of Kevin Ayers things that are nice as well.

Bjorn: A lot of those bands were just exciting — John’s Children.

Genesis: I’ve got their record. Marc Bolan was in John’s Children.

Bjorn: The Action, Creation, we had friends who were into a lot of mod / psych stuff.

Genesis: Oh, you’ll find all of those round the corner [laughs]. Also we loved the Incredible String Band.

Bjorn: I didn’t keep any of my Incredible String Band records….

Eric: 5000 Layers of the Onion.

Genesis: That’s not the best one, though.

Eric: That’s the one I got most into, although I like Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter.

Genesis: We like the way they do this basically acoustic music and do these long, strange, complicated songs. But then all of a sudden they’re singing about being an amoeba, or a butterfly or whatever. They’ll just twitch and change.

Eric: Did you ever see them when you were still in England?

Genesis: Oh yeah, cause some of the Exploding Galaxy joined them as the Stone Monkey.

Bjorn: It could sound sort of affected sometimes, to someone who was listening to it 30 years after it was recorded, like listening to “Pictures of Matchstick Men.”

Genesis: Oh, but I like that too.

Bjorn: It’s a good jam, but when you hear compared to other stuff it sounds like a really formulaic version of what a psych song is, flange the shit out of the vocal.

Genesis: Yeah, but the Incredible String Band was something that took me ages to get into. The people who liked it at university were people that we didn’t like. [Laughter] It was sort of nerdy, almost.

Bjorn: The Grateful Dead’s the epitome of that in the U.S. I can’t hang with all those jams, and shit like that, but some of those records are gorgeous.

Aaron: The story of the band is incredible.

Bjorn: Yeah, it seems like the quintessential punk band. It’s all fueled on acid money. They’re dosing five or six thousand people at a gig, playing whatever the fuck they want.

Genesis: We’ve got 20 CDs by the Incredible String Band, at least.

Bjorn: Are some of those bootlegs?

Genesis: There’s bootlegs, there’s live shows, there’s John Peel sessions.

Eric: Did you see the movie?

Genesis: Yes.

AL: Was there a movie about them?

Genesis: It’s really bad [laughs].

Eric: It’s like a pirate movie.

Bjorn: When you see photos of old Soft Machine with face paint and stuff like that, even that looks pretty hokey.

Genesis: We like stuff like that now, though. Our guitarist in Psychic TV now, David Max, he does face paint. But he does itbecause he’s so

kitsch. He can’t take it seriously. But then we try and be as silly as we can onstage.

Bjorn: I think people have a hard time not taking themselves seriously as musicians, or bands. When you look through an issue of MOJO or something like that, it’s just the most pretentious-looking photographs. When I look at it now, I just think, how exhausting, to keep that shit up.

Genesis: We have competitions onstage to see who can mess up somebody else in a song [laughter], and who can do the stupidest dance. You got to do stuff like that; otherwise it’s no fun.

Bjorn: Otherwise you’re watching MTV, basically.

Eric: I knew some friends on tour who had a fight in the van. They were all against the drummer. And every day the drummer fucked up the set, once, for every time they got in a fight, and would point it out. [Laughter]

AL: The drummer’s revenge.

Eric: Exactly.

[The conversation shifts to “Bohemian Rhapsody” for some reason….]

Genesis: That has to be one of the weirdest songs to get to No. 1.

Eric: I think it’s one of the only songs that’s done it twice.

Genesis: Has it?

Bjorn: ‘Cause once Wayne’s World came out, it was on the soundtrack to that.

AL: Oh, that’s right.

Genesis: But it’s a strange, strange thing.

Bjorn: I have a hard time getting into music with that degree of flamboyanc’y to it. [Genesis laughs] I guess ELO is pretty close to that….

Genesis: Yes it is [laughter], although Philip K. Dick loved ELO. Their harmonies are fantastic. You know they used to be part of the Move, right?

Aaron: Oh yeah, they’re pretty great.

Bjorn: They really seemed like they were outside of the whole psych thing, ’cause they seemed slick.

Genesis: Well, they were from Birmingham.

Bjorn: I don’t need to go back there [laughter].

Genesis: I don’t like Birmingham either.

Bjorn: We played on Hawkwind’s touring PA, and apparently it had been Pink Floyd’s. It was mostly gigantic bass bins.

Genesis: It is Pink Floyd’s, and it does go out, but it’s not very well cared for.

Aaron: And it seems like it’s more of a sculptural, architectural [thing].

Bjorn: This guy that owns this repair place here, EARS, used to be Rick Wright’s keyboard tech, and then he was Vangelis’ keyboard tech, the Sweet’s keyboard tech, this guy always drops some knowledge about….

Genesis: Saw the Sweet once.

Aaron: Oh yeah?

Genesis: They were great. We liked them. When they play live, they do long jams — 17 minutes or so.

Eric: Of, like, blockbusters?

Genesis: Weird, psychedelic blues. They’d go off.

Aaron: Did you see them in the U.S.?

Genesis: I saw them in Chi-ca-go. Of all places. In a sports bar.

Bjorn: I bet they’d go over great with the local sports bar crowd.

Genesis: Couldn’t believe that they were on. We were hanging out with Pigface and somebody – it might have been Chris Connelly – went, “My god, Sweet are playing, we’ve gotta go.” So we all stormed down to this sports bar near the baseball stadium and lo and behold, there they were! It was a tragedy, really, to see it. It was like 30 people.

Aaron: Holy shit.

Genesis: And we were the only ones who were into it [laughs].

AL: What year was this?

Aaron: Early ’80s?

Genesis: No, no, no this was the ’90s.

Aaron: Oh shit. [Laughter]

Bjorn: Who’s the dude you said, Chris Connelly? That’s the guy who wrote us, right?

Aaron: Yeah.

Genesis: He was in Revolting Cocks and Ministry.

Bjorn: He wrote us to see if he could send us some vocals throw on some Dice jams.

Genesis: He’s really sweet. He used to hitchhike down from Glasgow to Hackney, to my house, when he was about 15, hang out with the TG people. Ruined his life [laughter]. He just wrote a book actually, My Life as a Revolting Cock. It’s really good. It deals the shit on Al Jourgenson too. They are no longer friends.

Bjorn: We were talking about Ministry. They were a band that I never really got into. Aaron was pointing out that it was too catchy and not heavy enough. I kind of like the idea of that shit now.

Genesis: Wax Trax! was kind of an interesting label, they built up this library of bands that had a certain edge to them, KMFDM:

Eric: Wax Trax! was in Denver?

Genesis: No, they were in Chicago.

Aaron: I used to work at Wax Trax! when I was in Colorado. I used to pump the owner for information on the Chicago aspect of it and the bands.

Genesis: They were great; they signed Psychic TV and they sold bucketfuls of albums for us.

Bjorn: This blows my mind. My impression of the American independent music landscape has always been… it’s always seemed pretty hopeless.

Genesis: We sold 40 or 50,000 of Towards Thee Infinite Beat in a couple of months.

Aaron: Fucking inconceivable.

Bjorn: You’re speaking a different language, those kind of numbers. [Laughter] Drop a zero.

Aaron: No, drop two zeros. [Laughter]

Genesis: Well, that was the only time that ever happened to us. And it was great because I paid to record the masters, so I owned it completely.

Bjorn: A lesson I wish we had learned a while ago. [Laughter]

Genesis: I didn’t know any other way to do it, apart from the fluke when we ended up on CBS. We never got a fucking penny out of them – cause we did it this way with the holophonic sound, of course, it meant that every bit of money that we would have got from the advance went on that.

Bjorn: Is that a hard record to get?

Genesis: Steve-O is still bootlegging it. He just recycles all those albums over and over and he never pays anyone. So at any given moment, if he’s recycling, then it’s available. However, we’re in the process of doing the definitive two-CD set of it, cause I have all the alternate mixes and everything.

Bjorn: Have you ever heard Maryanne Amacher? I guess she studied under Stockhausen. This one CD — the only one I’ve heard — came out on Tzadik….

Genesis: Is she the one who did the star sounds, the radio waves?

Bjorn: This has to do more with…. I met her, and she told me had gotten really interested in recordings of cadavers’ eardrums. T,hey would send a tone in and she was talking about how the eardrum could be an instrument as well.

Alan: Yeah, she activates this stuff in your inner ear. You hear this thing that’s only going on inside your head.

Bjorn: It’s very physical. You feel like your ears are bleeding in a non-painful way, but it only works in an architectural space. You can’t do it with headphones; you have to listen to it at a pretty decent volume, on a stereo or a PA.

Genesis: I don’t know that, but it’s fascinating.

Bjorn: Throbbing Gristle was probably the first band where I heard of a sound making people sick. [Genesis laughs] People were shitting their pants, and this is one of the only types of music I’ve experienced….

Genesis: The most interesting was when we played the Film Coop. Two women said they’d had spontaneous orgasms. And we asked them what song it was so we could go back on the cassette and find the moment.

Bjorn: The G-spot on the tape. [Laughs] We have a history of people having seizures at the shows; was that ever a problem?

Genesis: Not knowingly. We’ve not heard of it. But, now, with PTV3, Eddie, the drummer, has seizures if there’s a strobe on.

Alan: Were you guys using strobes?

Bjorn: No, no; it was just from the music.

Aaron: Or just from having an epileptic person.

Bjorn: There’s been enough times that it’s happened. Now we have projections that are pretty strobe-y. So that heightens it, but I like the fact that you can be dealing with a medium that most people associate with one sense.

Genesis: Well it’s obvious, isn’t it? Sound is going in the flesh too. You’re being hit by it everywhere, not just here [points to ear]. The deep frequencies are literally vibrating your stomach.

Eric: I was reading that 33 1/3 book on 20 Jazz Funk Greats. It was in a bathroom, though, so I only had it for a couple of minutes. [Laughter]

Genesis: Well you were lucky.

Eric: The reason I brought it up is both sections I turned to used the word alchemy, and I was kinda curious now that you’re talking about sound giving you a physical reaction, it seems like it’s maybe an idea that’s followed your life?

Genesis: Well, we visualize alchemy. Burroughs talked to me about that too. In the Middle Ages, the alchemist was the person who had the most radical equipment – glass test tubes, little flames, mercury, and other elements. If you were going to be an alchemist now, it should include a Walkman, or a Holophonic recorder, or whatever is the most cutting-edge equipment. Alchemy is an ongoing organic process that’s at the edge of technology – pushing, breaking and reassembling it so that it changes physical and mental responses to something.

That’s what we were talking about, like turning six Walkmen into a keyboard and seeing what happens when you have random sounds from 12 places happening simultaneously. What does it do to the brain? Does the brain re-sift them and listen one at a time? Or is it overloaded, and then if it’s overloaded, which message goes in – my vocal, the guitar, or what?

Bjorn: Do you think that also applies to visual assemblages and collages too?

Genesis: Yeah, now we use the video more with Psychic TV. e make the music far more traditionally rock, we all jump around, do the broken leg dance and what have you. But while we’re doing that, the images are going past; we’ve distracted the filter. The images are really the rhetoric, or the propaganda, if you like.

Eric: That seems like a school of thought that has a body of knowledge behind it. Do you feel like that’s been informative, or do you feel like that’s been something that’s been peripheral? I mean, do you read that shit, or….

Genesis: Oh, I read about new maths and new physics, yeah. All the time. It’s fascinating. Everyday of my life, we contemplate the nature of reality, and the definition of reality, and the possibility that there is no reality, what was before there was nothing. Those questions obsess me. All the time.

Eric: Do you believe in Atlantis?

Genesis: No. [Pauses, then chuckles] No, but we believe that something happened somewhere that was disastrous that became a myth, or a parable, or a story. I mean that’s easy to see; it happens with people like you or me. I’m sure there’s some gig you did that there’s a story about that isn’t the truth but it’s an exaggeration of the truth. That’s how it happens. [Laughter]

After 10,000 years, that could become something quite different and seem either old fashioned or potent, depending on the state of culture at the time. So, we’re always trying to mess with the internal mechanisms of culture, far more than we’re trying to make good art.

Eric: Who do you mean by “we?”

Genesis: Well, we’ve actually been a bit lazy today, for simplicity, but normally we say “we” to mean me and Lady Jaye.

Eric: Ah, ok.

Genesis: We represent me and Lady Jaye in this dimension, and she represents us on her own. Not “we” the band.

Eric: Or popular culture.

Genesis: No. But we didn’t remember to define it at the beginning so we’ve been slipping back and forth.

Alan: I remember you talking about these paintings from Medieval times that depicted Jesus as a hermaphrodite?

Genesis: No, no — God, Adam, and Eve. All the original paintings that we know of of the Garden of Eden depict God, Adam, and Eve as hermaphrodites. Quite literally. And they were around around the time of the Holy Roman Empire destroying the Cathars, the heretics in the South of France, because they knew about the Virgin Mary being there. And the witches, because they knew all about pagan knowledge and medicine and so on, they were also destroying all the paintings. It was a coup. The Roman Catholic Church did a European coup which was very successful…. The divine state has to be both. It can’t be binary; it has to be unity.

Alan: There was also this exhibition I went to of Byzantine art. here were all these portraits of Jesus, and he was always black. You see some slightly later portraits after the west had infiltrated, and all of sudden it was this white guy with long hair and a beard. But the early depictions of him are not that at all.

Genesis: Like a dark skinned Arab.

Alan: Exactly. Which makes more sense considering where the whole story takes place.

Genesis: Of course. Now the Catholic Church, if you really look, make Jesus look like a tranny, very feminized. Very feminized.

Bjorn: That’s a popular look though. I feel like most women on TV, like Desperate Housewives, they all look like that. [Laughter]

Genesis: You only have to look in the back of the Village Voice. Seventy-percent of the sex service is now with she-males…. There’s been this really deep shift of heterosexual men who have been cheating on their wives by going to these she-males. That’s a huge ratio of supposedly straight men. What does this mean? We don’t know, but it’s interesting. We tend to think it reinforces our argument about evolutionary trajectory to the hermaphrodite.

Bjorn: That’s what we’re evolving towards, or….

Genesis: It’s a symbolic evolution towards inclusiveness, as opposed to separation. To us, that’s what it really represents. The reappraisal of the way society works, and the role that people have in the way they’re split male/female, good/bad, black/white, etc. But that’s actually becoming damaging to us in terms of our future.

Bjorn: I feel like technology is eradicating the distinctions in some ways. I remember seeing on the news how kids who are going to college are all best fuckin’ friends on the Internet, but then when they show up at school, they don’t know how to have a conversation with a human being. The internet is a medium that levels the playing field in this one way.

Aaron: That’s like the whole avatar kind of thing.

Bjorn: What’s avatar?

Genesis: A symbolic representation, an icon of who you pretend to be.

Aaron: Yeah, like something like Second Life, you heard of that?

Genesis: You can go and you can build a person, literally a three-dimensional…

Aaron: It’s like a game, kinda.

Eric: It’s virtual?

Aaron: It’s virtual. You can have sex, you can buy a coffee, sell your record, you can do all this different shit. And you can fucking work at a job if you want, or you can be like a serial killer.

Bjorn: It brings up weird questions.

Genesis: Lady Jaye and myself worked as dominatrixes at a dungeon for quite a long time. She did it for years. And the two most common things people ask for is to be made to look like a pretty woman, and to be fucked up the ass with a dildo.

Aaron: Man.

Genesis: Those are the two most common fantasies. So deep down, there’s a whole other language, and a whole other life going on. And things like you were just talking about with avatars, are giving people a safe way to start to check it out…. And then the whole thing with cosmetic surgery. Ten years ago, everyone in Hollywood was trying to say, “No, I’ve never had anything done.” And now they’re doing TV shows where people are boasting about what they’ve had done. So that’s also shifted from sort of a nasty secret to something to be proud of. Sadly it also made it something that could be used as a status symbol, which is a shame. But it’s getting cheaper all the time now.

Bjorn: There was something on the news recently about some women who had their asses done to look like J Lo’s, but it was an unlicensed doctor and he was using industrial silicone….

Genesis: Oh, no.

Bjorn: Their systems just shut down, and one of them died.

Aaron: Holy fuck.

Genesis: A lot of the transsexual women in New York that aren’t well off, they use that industrial silicone too. They have parties where they just sit there and inject loads of it into their asses. It’s so sad and bad, you know? They’re that desperate to be curvy, that they’ll risk dying young. I mean, how many old trannys do you know? Not many. So they’re dying young.

“There’s been a big

shift away from being

afraid of experimentation”

Bjorn: A lot of times, though, you have to wonder if that just has to do with the type of lifestyle anyway?

Genesis: Yeah, I know – it’s a hard lifestyle, too. A lot of them work as hookers to get money.

Bjorn: Yeah, I guess now you hear so much about meth within the gay community, but I imagine that it’s rampant.

Genesis: But under all of that is this definite shift in the west — obviously it’s different elsewhere — especially in the United States…. There’s been a big shift away from being afraid of experimentation. You know the words “down low”? We didn’t know that before. That’s quite a change

Eric: And every major celebrity has been outed as closeted, or in a very complicated, homosexual lifestyle. Even, like, Will Smith.

Bjorn: Tom Cruise.

Eric: Not that it matters, but it puts it in popular tabloids.

Alan: Actually I think a lot of his whole trip is due to having to be closeted this whole time, because he’s America’s sweetheart.

Genesis: America’s sweetheart? I don’t know what he is. He looks like a clone:

Alan: Like a Stepford Wife.

Genesis: I think he looks like he’s been cloned; I think he’s not the original one. I think the original one died in experiments:

Bjorn: Acting experiments. [Laughter]

Genesis: This is just the third generation copy.

Bjorn: A lot of his movies are kind of trash but I think he’s actually really good in a lot of them. He’s good in Risky Business, and Top Gun is a wallpaper kind of movie, but he’s good in that. He’s good in Magnolia….

Genesis: What was that one about the rich man with the distorted face?

Eric: Vanilla Sky.

Genesis: Yeah, that was alright.

Aaron: He’s good in Eyes Wide Shut.

Bjorn: He is good in Eyes Wide Shut, but he always plays a similar dude – this guy who’s tightly wound and:

Eric: Eyes Wide Shut was supposed to be Kubrick’s anti-Hollywood movie – his mind control, sex slave movie. But I rewatched it trying to figure it out, and I thought it was just fucking boring.

Aaron: No, man, it’s fucking good.

Genesis: You like it?

Aaron: I think it’s great. In a way, it’s just a trite, domestic quibble type of thing, but in this other way, it deals with people’s fantasies. They’re not even that dark or dangerous; it deals with this kind of domestic fantasy. It’s almost like a throwback to an earlier kind of safer fantasy. The tone is completely unique, and I feel like the scale on which it was made and released is like you having the budget to do your weird record…. When it came out it was so huge but it satisfied no one. [Genesis laughs] Even hardcore Kubrick fans were like, “I don’t know, it wasn’t that great.”

Genesis: Do you give it two thumbs up or two thumbs down?

Aaron: Two double thumbs up.

Genesis: [Applauds] That was a very, very good critique. [Laughter]

Bjorn: The Shining is one of my favorite movies ever, and it’s one of the scariest movies I’ve ever seen.

Genesis: It’s truly spooky, isn’t it?

Eric: Have you guys ever seen Let’s Scare Jessica To Death?

Aaron: Oh yeah, that’s a cool movie.

Eric: I just watched that last night – a scary ’70s woman-going-insane movie.

Aaron: It’s well-crafted, but it’s cheap. If you look at the lighting setups and shit, it’s gritty, but that chick is totally unbelievable.

Eric: They’re like retreating to this house in the country….

Aaron: She just got out of an institution, so like ’70s, hippie…

Eric: There’s, like, maybe a spirit….

Aaron: And the soundtrack is like a shitty Korg Polysynth. [Laughter]

Bjorn: There’s very few creative projects think are as tight as 2001. That movie pushes ideas in every single direction. Visually, it’s gorgeous, from a forward-thinking point of view. There’s so much input from designers, and most of the shit they show in that is stuff that’s pretty much in existence now.

AL: The way he used music in those movies has become so identified with the music now. Like Clockwork Orange or even some of the classical music he uses in 2001.

Genesis: Where do you see your music in 10 years? Would you like to do film soundtracks? I know we’d love to.

Eric: I think there’s something exciting about taking something that you do and putting it with something that you don’t do. Not that you or us couldn’t make a film, but in 10 years…. I have no fucking clue. Ten years ago, if you had asked me, I would not have expected to be anywhere where I am right now.

Genesis: Nor would we have expected to be at fucking Coachella, right? [Laughter]

Eric: Touche. I would love to see where it goes. Like you were saying, I think there’s a type of attitude where you want to take your ideas somewhere, and then there’s the type of attitude where you’re like, “I want to see what happens.”

Bjorn: If you’re doing things that are left of center with any sort of longevity, you have to have ideas. And sometimes they don’t jibe with what people like. There was a weird point in New York where all of a sudden every magazine was writing about bands from here — the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Liars, the Strokes – and we were kind of fortunate, or unfortunate, enough to get noticed in this way. We did a record that people seemed really receptive to, and all the people we knew who made noisy music were like, “This is really weird. There’s never this many people at these kinds of gigs.”

You either have to have a really tight relationship with the people you’re working with, or some sort of support to make decisions where you know you’re going to disappoint and piss people off. I don’t think it’s always coming from a bratty place. You have your ideas, and at the end of the day, that’s all you’re going to be remembered by–these things that you’ve done.

Genesis: Do the Liars still even exist?

Bjorn: I think so.

Genesis: The Strokes? We never hear about the Strokes. So you’ve lasted longer than them, you see. Which is an interesting point. Look at TG – how it’s lasted longer than all those other people who had hit records then.

Bjorn: Longer than Soft Cell.

Genesis: So that’s why we’re asking, because it’s often the more experimental people that end up being the ones that are remembered, because they’ve done something that’s actually changed perceptions.

Aaron: I think it’s different if you’re at the level where you’re just living off of the music. This is one of the main things with us, and some of our friends. We look at people we know and are like, “What the fuck? How are they making a living off music, and we’re working these shit jobs and can barely survive? There’s a certain kind of freedom that comes with that, though.

Genesis: There is. You’re not censored by the need to keep making the money.

Bjorn: Everyone’s had a friend whose band got popular, and then they fully went for it, started dressing in a bunch of douchey clothes:

Genesis: Doing the whole thing.

Bjorn: Yeah, and everyone we know who’s done that no longer has a band.

Genesis: Well, let’s assume that you’re the young, new version of TG, which is fair enough. In 10 or 15 years, you’ll be at that 25-year mark, where everyone reforms and people like Coachella ring up. What’s that going to feel like? Will you be playing all the way through?

Aaron: I have a hard time thinking people are going to be that into it, given the current state of things. We eke it out right now. It’s really hard to imagine.

Bjorn: This is the only band I’ve played in, and we’re brothers, and Aaron has basically spent as much time with us as Eric and I have spent together in our lives…. I don’t want to play with anybody else, really. I think when you play with people a certain length of time, there’s some stuff that you don’t have to talk about, and that becomes kind of essential in getting ideas across.

Genesis: We have this theory that you’re going to end up in the same sort of place that we’re in. [Laughter]

Eric: I don’t know if that’s a threat or a promise. [Laughter]

Genesis: Nor do we. [Laughs] We’re not sure if we like the idea of going onstage at Coachella. It’s probably the most scary thing that’s ever happened… Here’s the problem: the TG that got booked by Coachella is the mythical TG, right? The myth, the weird anecdotes, but that’s not me now. So that means they want me to act Gen when Gen was 25.

Bjorn: But what they love about the old one is the fact that you wouldn’t have acquiesced and done what they wanted, at that time.

Genesis: Is it, though? Or is it that they want that snapshot? They want just once to have that gratuitous snapshot of what it was like 25 years ago. It’s a very strange place to be at.

Eric: It’s not like you’ve been making Throbbing Gristle songs since ’75.

Genesis: No. But that’s the problem…. I don’t recognize that angry young person that was nuts and drank whiskey, taking Valium before they went onstage. Don’t know who that is, really. I’m not angry.