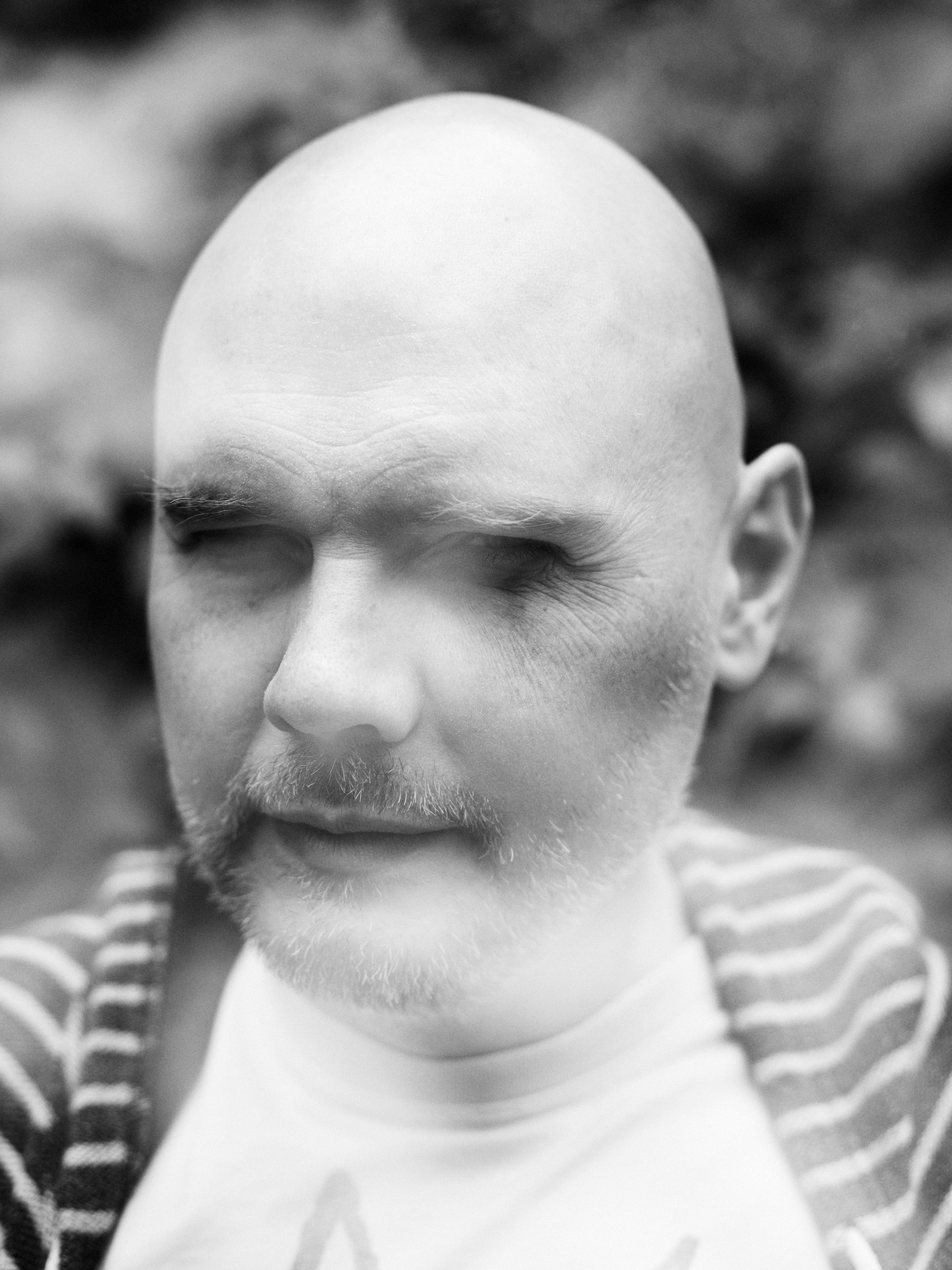

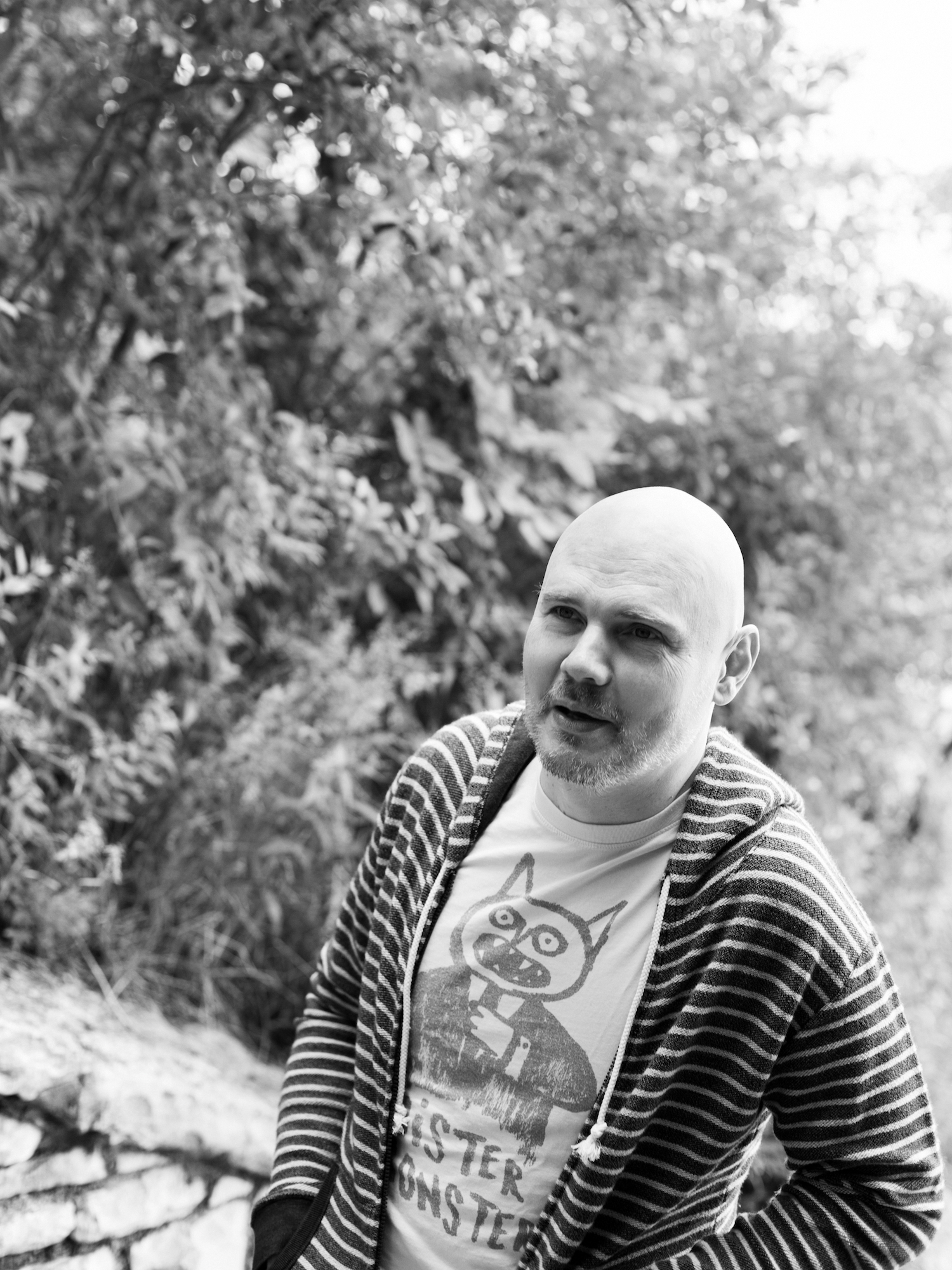

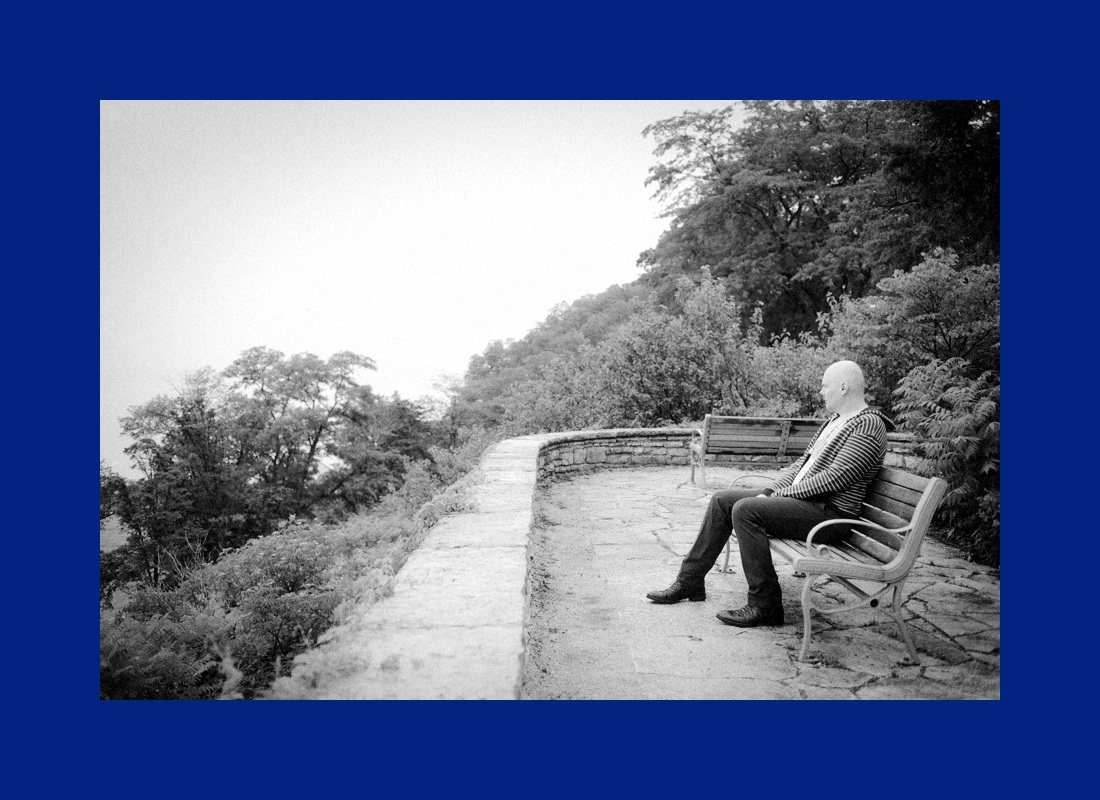

Photography BRIAN SORG

Interview ANDREW PARKS

If actions truly speak louder than words, then the most telling move in Billy Corgan's 30-year career was when the Smashing Pumpkins frontman bought the National Wrestling Alliance. Not because the brand has been on a downward spiral since the late '80s, or because Corgan is known for brash and impulsive behavior, like spending more time with a widely shunned conspiracy theorist (Alex Jones) than actual journalists.

No, the NWA deal says a lot about the singer/string puller as a person, from his love of sports—he wanted to be a jock until he didn't make the team freshman year—to his recurring role as one of modern rock's leading raconteurs. Or as he said in a recent New York Times interview, "I'm a class-A heel. I'd put me two, behind Lou Reed, who's the king."

It's hard to blame him when so many writers seem determined to hate everything he's done since the '90s. Why, just last night, a music critic at the Star Tribune slammed the Pumpkins' current Shiny and Oh So Bright tour for its "bloated" three-hour sets—something fans appreciated, since it leaned so heavily on their hits—and Corgan's omnipresent ego. Which kind of misses the point. Of all the alt-rock bands that topped the charts in the '90s, the Smashing Pumpkins was the one that wanted to be rock stars, that worshiped Black Sabbath and Bauhaus. Hence why they're covering nothing but the classics these days, including David Bowie's otherworldly "Space Oddity" and Led Zeppelin's seemingly untouchable "Stairway to Heaven."

"On a personal level, I'm a human being, right?" Corgan said in a self-titled interview a few years back. "And I don't feel understood. Instead of being celebrated for bringing a different opinion into the world, fostering it, and at times, having success with it, I'm treated like, 'Why do you want to keep doing that?'"

We try and tackle that question below by sharing our entire conversation—a rare and revelatory look at Corgan's views on everything from organized religion to the rise and fall (and rise) of rock 'n' roll. One note: We spoke around the release of the last official Pumpkins LP, 2014's Monuments to an Elegy, which featured the one-off drumming of Tommy Lee and the wing man riffs of Jeff Schroeder. A full-time member of the band for the past decade, Schroeder can now be seen in press photos alongside longtime drummer Jimmy Chamberlin and guitarist James Iha, who are back at Corgan's side for the first time in 18 years. (Bassist D'arcy Wretzky claims she was essentially written out of the trio's reunion—something Corgan disputes, of course.)

Interview ANDREW PARKS

If actions truly speak louder than words, then the most telling move in Billy Corgan's 30-year career was when the Smashing Pumpkins frontman bought the National Wrestling Alliance. Not because the brand has been on a downward spiral since the late '80s, or because Corgan is known for brash and impulsive behavior, like spending more time with a widely shunned conspiracy theorist (Alex Jones) than actual journalists.

No, the NWA deal says a lot about the singer/string puller as a person, from his love of sports—he wanted to be a jock until he didn't make the team freshman year—to his recurring role as one of modern rock's leading raconteurs. Or as he said in a recent New York Times interview, "I'm a class-A heel. I'd put me two, behind Lou Reed, who's the king."

It's hard to blame him when so many writers seem determined to hate everything he's done since the '90s. Why, just last night, a music critic at the Star Tribune slammed the Pumpkins' current Shiny and Oh So Bright tour for its "bloated" three-hour sets—something fans appreciated, since it leaned so heavily on their hits—and Corgan's omnipresent ego. Which kind of misses the point. Of all the alt-rock bands that topped the charts in the '90s, the Smashing Pumpkins was the one that wanted to be rock stars, that worshiped Black Sabbath and Bauhaus. Hence why they're covering nothing but the classics these days, including David Bowie's otherworldly "Space Oddity" and Led Zeppelin's seemingly untouchable "Stairway to Heaven."

"On a personal level, I'm a human being, right?" Corgan said in a self-titled interview a few years back. "And I don't feel understood. Instead of being celebrated for bringing a different opinion into the world, fostering it, and at times, having success with it, I'm treated like, 'Why do you want to keep doing that?'"

We try and tackle that question below by sharing our entire conversation—a rare and revelatory look at Corgan's views on everything from organized religion to the rise and fall (and rise) of rock 'n' roll. One note: We spoke around the release of the last official Pumpkins LP, 2014's Monuments to an Elegy, which featured the one-off drumming of Tommy Lee and the wing man riffs of Jeff Schroeder. A full-time member of the band for the past decade, Schroeder can now be seen in press photos alongside longtime drummer Jimmy Chamberlin and guitarist James Iha, who are back at Corgan's side for the first time in 18 years. (Bassist D'arcy Wretzky claims she was essentially written out of the trio's reunion—something Corgan disputes, of course.)