Like many outsiders, we were fascinated by a very specific vision of Japan at first — the one that’s bathed in neon and beamed from the near future. And yet, the more time we spent there, the more complicated this picture became.

While there’s no denying the inherent draw of, say, a Robot Restaurant or Kawaii Monster Cafe, there’s a whole lot of history — much of it quite complicated, and bleak — lurking just beneath Japan’s bright surface.

Over the past three years, Meitei has made cultural preservation his mission on both a creative (a trilogy of terrific albums, culminating with this month’s Kofū LP) and personal level, bringing the past back into the present in ways rarely seen within his own circles.

“I would like to say to modern Japanese people that Japan is more than just Tokyo, Kyoto, sushi, or anime,” the Hiroshima-based producer says while discussing the world’s obsession with wabi-sabi. “There is so much to explore in Japanese art and cultures.”

To put all of this in perspective, we asked Meitei to explain some of the central themes within his recent work, and the many hours of research that have reshaped his own views of a country that’s constantly misunderstood, even by its own people….

1. KWAIDAN

In modern Japan, Kwaidan is often used as ghost-themed entertainment with the aim of shocking people. It is similar to the horror movies that we see today.

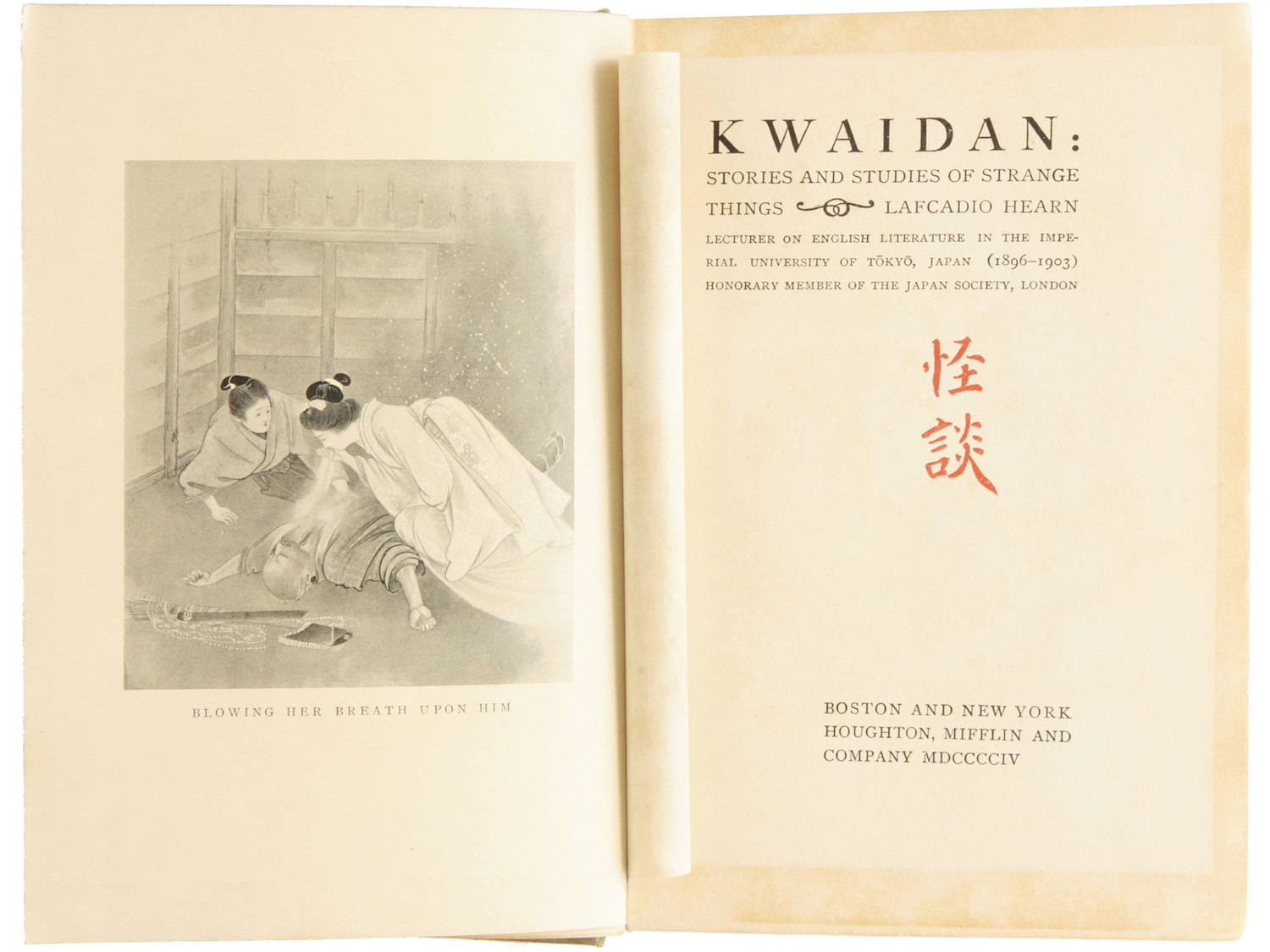

Wondering about the origins of Kwaidan, I read that it is rooted in from folklore. The Japanese scholar Kunio Yanagita, who died in the Meiji era (1910), wrote a book about lost folklore and legends called Tono Monogatari. And around the same time (1904), Kwaidan was published by Koizumi Yakumo.

Taking information from these books, the origin of Kwaidan is different from the modern take. The old Kwaidan is a mood that is simply more profound than just shocking elements. For example, it can be an indescribable and uneasy feeling when you can sense something from the mountains’ depths as the vegetation at night sways in the damp wind.

Interestingly, Koizumi Yakumo was a foreigner (born Patrick Lafcadio Hearn of Greek-Irish descent). I think the darkness of Japan would have been fascinating to him at that time. But what I find most interesting is that modern Japanese feel like the lost heritage of Japan is exotic. I was one of these people. That was what led and inspired me to create the album Kwaidan.

2. OCHA

When I lived in Kyoto, I made an EP called Yabun. Later, “Yabun” was included on my second album Komachi.

At that time, I was excited to discover various kinds of Japan [culture] every day. Japanese tea is one of the themes that I want to reproduce as a mood; I would like to make an album that focuses on Japanese tea in the future.

When it comes to Japanese tea, tradition and inheritance always exist. It can be said that the remnants of the old-fashioned hierarchy still remain. However, the flow of such a tea scene these days may also be leaving from the lost hands of legendary masters such as Sen no Rikyu.

Near my apartment, I have a friend who restored an old Japanese house and runs a tea stand. He owns his own plantation and produces Tea Factory Gen.

He takes the entire process of bringing the tea to market seriously. Picking everything by hand with the help of some colleagues, he has eliminated the mechanized production methods that were important to post-industrial Japan pioneers in this field.

He traverses the example of the unquestionably huge Japanese tea concept that has been handed down from generation to generation. And he respects the predecessors of the past and moves forward on the modern tea scene. I think his style will be unique to the contemporary Japanese tea scene in the future.

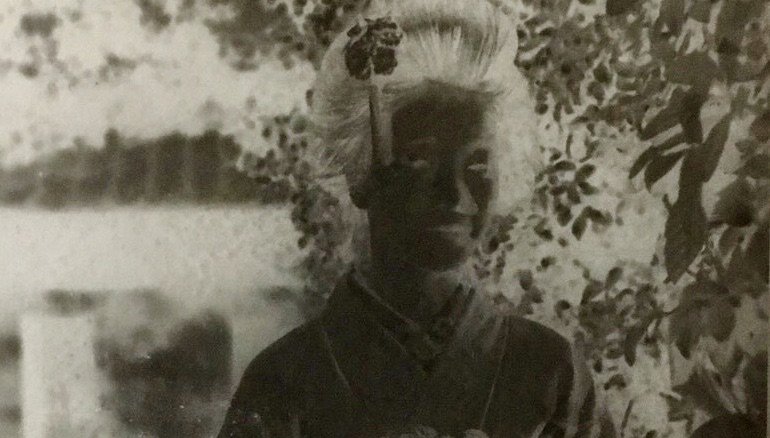

3. SADAYAKKO

As far as I know, the Kawakami troupe are said to be the oldest entertainers in Japan. They were probably the first Japanese to perform in a foreign country and had traveled around the world.

In 1899, the Kawakami troupe, which consisted of director Otojiro Kawakami and his wife Sadayakko Kawakami, took the stage in such American cities as Chicago, Boston, San Francisco, and New York. They showed off the unique mood of the Orient over there. It has a very interesting historical air, so I sampled them in the album Kofū as a twin tracks “Sadayakko” and “Otojiro.”

Modern Japanese know little about the Meiji era — I used to be one of them — so I sought to rediscover the Kawakami troupe’s mood through my music. I hope that listeners can experience this piece of Japan’s lost history on Kofū.

The picture above is from 1901; it’s from an old poster by Pablo Picasso.

4. YOSHIWARA YUKAKU

The love and sexual theme park that has existed in Japan for over 300 years is the area called Yoshiwara Yukaku. Women who were trafficked gathered here. They had no choice but to have sexual intercourse with men in Yoshiwara — sometimes even with other women.

Oiran (a higher class of courtesans) was expressed as a track in Kofū. Their days were so hard they stretched the limits of human beings. They spent their entire childhood and adulthood in Yoshiwara. There must have been a lot of mistreated women here.

During the Edo period, an ugly infectious disease called baidoku spread throughout Yoshiwara Yukak. Such illnesses struck many women due to having sexual intercourse in an unsanitary environment.

Each oiran has its own rank, and Katsuyama was at the top of it. I’m sure it was a very spectacular life. Katsuyama was aware of the challenging circumstances and was a renowned figure in Yoshiwara. However, I don’t know if she managed to eradicate the problems, as there is no detailed ancient documentation about her. Perhaps, that is why there is something so enigmatic about her.

Generally, when a woman enters through the Yoshiwara gates, she cannot leave until she is old. However, within about five years, Katsuyama was said to have left Yoshiwara in glory. Perhaps an incredibly rich man offered a tremendous amount of money to take her away from Yoshiwara.

I attempted to translate her aura into music with the tracks’ Oiran I’ and ‘Oiran II.’ The two tracks are collected in the album Kofū. I thought I couldn’t express her in mild ambient music this time around. I think she would have been fierce, intelligent, and gorgeous. And I’m sure there was darkness behind it.

5. LOST WOMAN

I wonder how Japanese women existed in the past and what their role was in society during the bygone eras. In some of my favorite animated films directed by Hayao Miyazaki, such as Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Princess Mononoke, a brave woman often appeared. I was very interested in it for some reason. We men have often been easily given an advantage in this Japanese society because that concept has been ingrained in people’s minds for a long time.

But nowadays, more and more people are questioning such a concept. There are more calls for women empowerment and gender equality. As a result, the situation in modern Japanese society is improving little by little.

However, men still dominate workplaces and various fields such as the political scene, much more than other developed countries. I’m sure Japanese female ancestors have been treated unreasonably and misjudged more than we thought in the past.

Despite that, I believe they have continued to live a delicate way of life. It is sometimes fragile, but sometimes it symbolizes the strongest spirit of patience. It may be the lost Japanese women who have such human beauty. Some old photos of Japanese women seem to be able to capture this aura.

6. WABI-SABI

Wabi-sabi is a quintessential Japanese aesthetic that is inherited both academically and traditionally.

For example, a tea room called Tai-an was designed by Sen no Rikyu. This is the place where the wabi-sabi mood is based on the old concept of tea.

Separately as a single word, wabi and sabi seem to have different meanings. Wabi is sad, nostalgic, and in awe of the microcosm. Sabi is lonely. And in modern times, I feel that sabi is also understood as aging. When these two characters are put together, it forms the wabi-sabi we know as an aesthetic.

What’s interesting is that foreigners tag rustic scenes, objects, and furniture with #wabisabi. There was a time when I was looking for a book to dive deeper into the wabi-sabi philosophy and, ironically, the most interesting one I found was written by a foreigner.

His name is Leonard Koren. He also published a magazine called Wet in the past. Koren’s description of Wabi-sabi is very concise. And his view on wabi-sabi is similar to mine.

Both Yakumo and Koren, who wrote Kwaidan, came to Japan from abroad. All of these authors saw Japan and offered very different perspectives. I am very fascinated by it.

7. LOST PUBLICATIONS

In contemporary Japan, many people work hard to do what is necessary. It becomes a form of mindfulness practice that benefits society. Vice versa, many Japanese abandon certain practices, and things deemed unnecessary to people.

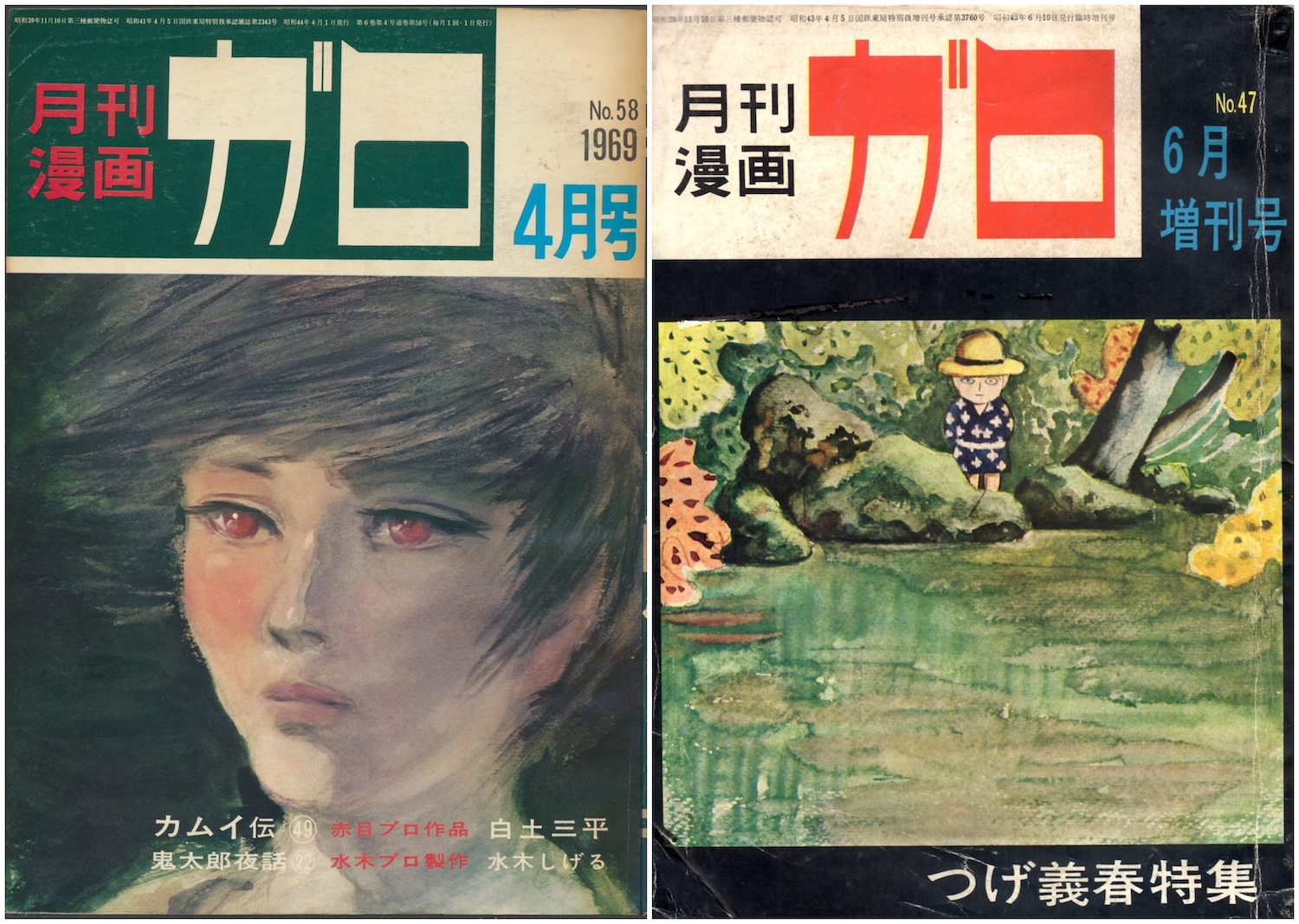

However, examining the past, we can discover that some people were doing rather strange things. One such example is an old magazine founded in 1968 called Garo. It focused on the world’s mysteries, and there was a darkness that could not be told.

It was prevalent in Japan at that time until the ’80s. I think it’s a very interesting episode.

I visited a bookstore a few years ago and bought some old Garo issues. They were being preserved for collectors, in close to dead-stock condition. With many old vintage books, the interior of the store was a very different and interesting space. It also had a peculiar smell of mold.

Recently I visited the bookstore again but sadly realized the store is closed for good. In a way, modern Japan is going through a paradigm shift. Japanese society is renewing itself like a human cell every day; the Taisho and Showa eras’ mood is disappearing from contemporary society and being replaced by the Reiwa era of the 21st century.

Especially in 2020; I think that many shops in the previous age vanished due to the influence of COVID-19.

8. MUJŌ

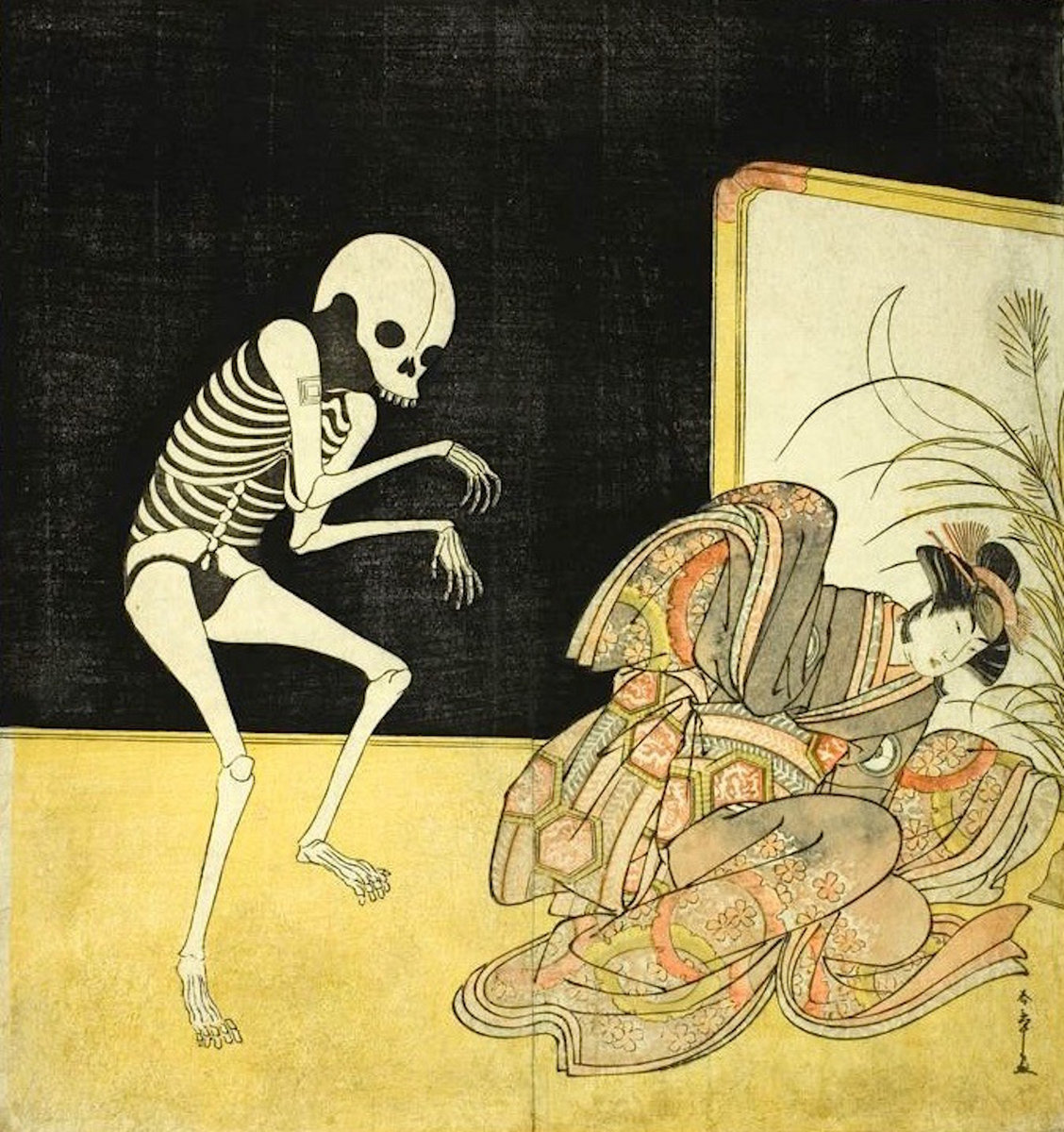

Sometimes I admire the personal history behind Japanese history. My friend’s late grandfather drew this picture. This contrasting perspective of a skeleton and a human being with skin was often drawn in the Edo period. The old man who drew this picture is a person who lived in the Showa period.

Interestingly, Japanese ancestors have often contrasted skeletons with humans to express the concept of mujō. It’s a transition of time; the reality we see is an illusion, and the illusion turns into reality.

I think that such consciousness remains in modern society. In other words, as the days go by, such a Japanese concept resides in the paintings of this anonymous artist.

But maybe it’s not limited to Japanese people. Everyone on Earth faces death. The Japanese seem to express their view of life and death in various styles. This picture is unique.

9. MOOD

Japanese people are diligent and always follow the rules. But so many people don’t know why they need to follow the rules. So they are reluctant to stop and think about things. Partly because of that, there are many good craftsmen in Japan but fewer creative producers.

Many Japanese live a mechanical life. Here’s an example to illustrate this: They stop when the light turns red, but they don’t know why they stop. They think they stop because that’s the concept. They perceive it as a stopping concept. They know it as a concept more than they know about the dangers of crossing the red. So they are not always good at producing things.

On the other hand, they need an example. So Japanese people are always good at imitating. They are more likely to imitate better than the real thing.

This strange Japanese attitude has cast a shadow over modern Japanese society. Many Japanese are unable to believe in their senses and suffer from anxiety and fear. The number of people who commit suicide is on the rise.

Modern Japanese people are mentally impaired by working hard on what they do not understand. In today’s world, many Japanese are required by society to accomplish things without knowing the meaning. The Japanese who question are perceived as one of the troublemakers in society in general. Especially among workers who did not have the proper education at an early age. Therefore, the modern Japanese ego is growing and becoming over self-conscious, which is unhealthy for society.

I believe that modern Japanese society needs to be more tolerant. Without it, it would be impossible to accept many things. Japanese people today are in denial with each other. So they don’t want to associate with people of different income levels or people who are not interested in them.

I want to cross these social boundaries. I believe that this is how we build a tolerant society and create a better mood for all of us in Japan….