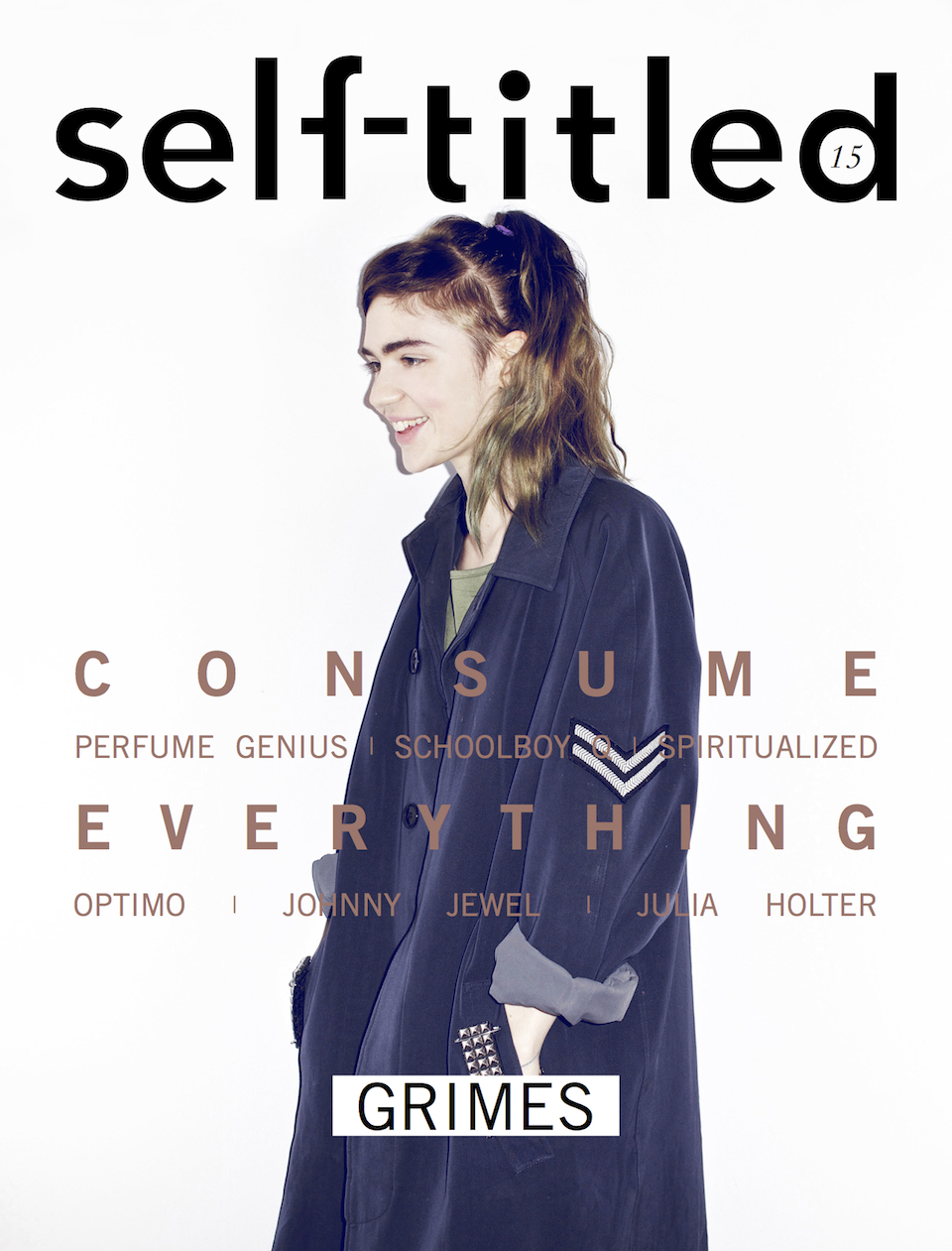

The following exclusive feature is taken from the archives of our digital magazine. Read the original version by clicking the cover below, and check out more long reads like it in our free iPad app.

Photography ALAN CHAN

Words DANA DRORI

“Sorry I’m also stretching as we speak, which is why I’m facing sideways.”

It’s January, after midnight in New York, and Claire Boucher’s face is streaming through my laptop. I haven’t seen her since October—when Claire and some of our friends came to New York for CMJ, when I experienced my first (and last) job as a Grimes backup dancer, and when we ate dumplings, drank beer, and sat on my couch.

It’s just after 9 for Claire, who is 2,500 miles away in Vancouver, riding out the last week at her parents’ home before embarking on a European promo trip and US tour. She looks energetic and put-together, despite the fact that she’d taken a bunch of sleeping pills at 5 a.m. the night before and awoken at 4 that afternoon. Her bedroom walls are bare, and aside from the unmade bed on which she is stretching, her room seems empty. Or maybe Skype just makes it seem that way.

“I’ve been here two months,” she says, sounding a bit stir crazy. “My life is incredibly boring right now. I wake up, answer e-mails and do interviews all day, practice… It’s just work from when I wake up to when I go to bed.”

It’s difficult for me to imagine Claire’s life as boring. In the past year, she has toured extensively (with fellow Canadian bands and friends such as Silly Kissers, Pat Jordache and Austra), logged a dozen South by Southwest sets and opened for Lykke Li. She’s been praised in The New York Times and Vogue, and as we chat, Visions, Claire’s much anticipated “sci-pop” (her words) LP under the moniker Grimes, is about to see release in the US via 4AD.

Claire’s short cloister in Western Canada is only the calm before another storm of shows, interviews and transience. But such, she says, is life on tour. “The longest time I’ll spend in any given place is, like, a week,” she explains. “I don’t have a home; there’s no consistency.” The schedule can be tough, and Claire has decided to tour with the band Born Gold (né Gobble Gobble, from Edmonton), rather than our mutual friends making music in Montreal.

Born Gold, Claire notes, is straight edge, ultimately a key reason for inviting them. “I can’t have any drugs or alcohol because I’m on the edge of sanity right now,” she says. “The main issue of me touring with anyone from Montreal—and the main reason I moved out of Montreal, actually—is because I just needed to get away from the drugs and stuff. I mean, you know how Montreal people are.”

Having been one myself, I do. I really do.

AND THEN THE COPS CAME

“Was I on mushrooms at a Braids show?” Claire asks about the first time we met.

This is not the memory I have. From what I remember—Montreal now reduced, for me, to a blur of extreme temperatures and extreme parties, running through fountains on MDMA during heat waves and finding friends passed out drunk in the snow—Claire and I met on the balcony of our mutual friends’ home. It was summer. There was barbecue. She had just dyed her hair blonde and cut her own bangs, but the bleach didn’t take, and her hair had turned greenish yellow, like parched grass.

Back then, Claire’s songwriting career lived in the darker realms of Montreal’s music scene, with shows and after-hours parties at DIY loft venues like Lab Synthèse and Silver Door—cramped and sweaty spaces that sat on the edge of the city’s artistic and industrial neighborhoods, where everyone was on drugs and the cops almost always showed up to shut us down. Set times started late and later, often around 3 a.m., when most people were too fucked up to pay proper attention, anyway. Which might be the best type of audience when you’re just learning how to make and perform music.

“They were all pretty bad,” Claire says of her earliest sets. She played her first show under her own name at Lab Synthèse. “I would just forget the songs while I was playing,” she remembers. “I probably played for, like, 10 minutes. It was a disaster.”

“She made these sort of cowboy songs,” says Sebastian Cowan, Claire’s friend since eighth grade, now her manager and founder of the indie label Arbutus Records. Claire met Sebastian when she’d started dating one of his friends, and then they all moved to Montreal. (For the record, Claire retorts, “I wouldn’t call them cowboy songs! I just used the ukulele…. Ugh, I hate the ukulele.”) Seb pushed her to pursue music seriously and urged her to contribute to his developing record label, which was then, he admits, “just me burning CDs.”

Claire’s early songs were psychedelic and experimental, playing with noise and dark, electronic sounds more than structure— appropriate for Montreal’s smoky lofts with less-than-stellar sound systems. She learned from her friends and fellow Montreal musicians. Blue Hawaii’s Alex Cowan taught her how to use GarageBand, which she now uses to produce her songs, and by watching artists like Sean Nicholas Savage (for whom she used to sing backup vocals), Dave Carriere (of the bands TOPS, Silly Kissers and Paula) and Braids, she gleaned songwriting fundamentals. “I’d look at these people and learn, ‘Okay, so you need lyrics, and you need to write a verse, and you need a chorus,'” she says. “Otherwise, it would just be psychedelic rambling that goes into space.”

Visions—strange and ethereal, yet tight and clean—is the culmination of her development. Some songs, like “Nightmusic,” are explosive and erratic, while others, like “Be a Body,” have a richer, more sensual build. Her soft, avian voice can feel transcendent, yet she grounds the music in visceral rhythms—shiny beats that make you dance, even if you don’t want to.

GRIMES’ TOP 5 MARILYN MANSON TRACKS

1. “Sweet Dreams”

2. “Nobodies”

3. “Dope Hat”

4. “Fight Song”

5. “Disposable Teens”

Claire acknowledges the city of Montreal itself, in addition to the people living there, in allowing her to indulge music. Cheap rent and easy access to bars and venues had us all living on the same adjoining two blocks on the cusp of Mile End and Outremont—an area akin to the Brooklyn border between Williamsburg and Greenpoint. Everyone was just up the street or around the corner, and shows were a short walk or bike ride away. The neighborhood is a haven for artistic types, who, without the pressure of needing a full-time job, can literally afford to spend time on creative projects. Artists can earn rent and living expenses with just a couple days’ work or through extensive grants from the government (or, for a lot of those still in college, from their parents). It’s the kind of surreal hipster utopia that Portlandia parodies, but it also catapulted Claire into making music.

At the same time, the constant late-night partying, regular access to drugs and general lack of responsibility took its toll. Claire watched as one of her best friends became a drug addict—“I’m so sick of walking home from somewhere and finding him blacked out, lying on the ground,” she says—and her own penchant for partying became overwhelming. “[When I return to Montreal] I’m, like, totally addicted to speed,” she confesses, “and I’m sick all the time.”

Life can become inert when everyone lives just down the block, shares the same interests and likes to party the same way. “It was obviously an incredibly great and productive place,” she insists. But as touring started to become a routine, Claire seemed ready to leave.

A VISION OF PERFECTION

About a year after we met and had both left Montreal, Claire and I are at a wig shop in NYC’s East Village. She is staying at my place for a couple nights, about to open for Lykke Li at Webster Hall, and has decided, nally, to invest in a black wig, rather than dying her hair black on periodic whims. After much deliberation (and a bit of haggling), she chooses not one wig but two: a shoulder-length black one with bangs and a long platinum-blonde ponytail attachment that makes her look part elf, part She-Ra, princess of power. It’s how I imagine her looking when I listen to her song “Genesis.”

“I like to aestheticize every experience as much as possible,” Claire once said to me. “Like taking yourself and making the most dramatic situation of your physical being—I like that idea.”

She changes her appearance regularly, particularly her hair, playing with color and shaving certain sections. “I’m super addicted to adrenaline and changing shit up,” she says. Which also explains her stick-and-poke tattoo habit: Every time I see her, Claire has new ink, the most recent being the Triforce from Legend of Zelda, which she did with her cousins to commemorate their days playing the video game.

Between the wigs and the tattoos—not to mention her love of medieval culture (she wrote her college thesis on Hildegard of Bingen) and sci-fi (she’s a big Dune fan)—Claire’s image leans as much toward the strange and otherworldly as her music. Even the self-made cover of Visions—a skull, eyes and Russian letters—evokes the edgier side of obscure.

Claire plans to film a music video for every song on Visions—her first, for “Oblivion,” was directed by Emily Kai Bock, Claire’s friend of six years—and talks about the record using visual references, likening it to movies such as The Fifth Element and the Japanese anime Ghost in the Shell. “I’m more influenced by things that I see and translating that into sound than things that I’m hearing,” she says.

Onstage, however, her live performance is raw and minimal. Without band accompaniment, she moves frantically between her sampler and keyboard, leaning in when she plays and tucking the microphone between her shoulder and ear when she’s not singing, which makes her look like a DJ spinning records. She holds the mic with one hand as she sings, her free hand moving in rippling gestures. Watching her petite, pale frame create an expanse of sound from behind her keyboard is, in itself, quite striking.

Claire can be shy—she even was with me for the first few months we knew each other—and not as assertive as she’d like to be. “I used to have the worst anxiety,” she admits. But working with friends has afforded her the comfort she needs to put as much of herself as possible into her work. “I try to abstract the lyrics,” she says. “Most of the songs are sort of driven, weirdly enough, by my love life, which is really silly.”

Some things about Claire’s love life that she will state on the record: “It’s way more hectic than it needs to be,” and it’s always “a dramatic affair.” (I laugh when she says this, remembering that even before Claire became lauded as Grimes, she always had many, er, No. 1 fans.) But leaving Montreal for life on tour has made her relationships—romantic and otherwise—“super transient and weird.”

This constant state of flux evokes conflicting desires for Claire. “There’s no sense of closure or continuity,” she says. But a want for more— whatever that may mean—is what seems to propel her. This, she says, is what Visions is about—an “idealized version of life… a vision of perfection,” a perfection that is always elusive.

POSTHUMAN AND HARDWIRED

Claire doesn’t own a phone. This never seemed strange to me in Montreal, where it’s easy enough to maintain a social life by simply going for a walk.

“People would just show up at my door,” Claire remembers. “My social life happened because everyone I knew lived on that block.” But on the road, with interviews and meetings and navigating new cities, she’s learned to rely on e-mail and Google Voice, when necessary.

“It’s really important to be disconnected from the digital world,” she writes in an e-mail, “or else you give in fully to being a cyborg, which simultaneously intrigues and terrifies me.” Disconnection, in other words, lets her choose when to be social and when to remain more private. “I hate it when people can contact me, too,” she adds, punctuated by a “haha.” Even her e-mail account has an auto-reply that reads, “I don’t have a phone or regular Internet access, so it might take me a while to respond.”

When Claire’s in New York, it’s easy for us to meet up. She’s usually with Seb, her manager, who assumes telephone responsibilities, but otherwise, the Internet is Claire’s primary tool for interaction.

Though she is often difficult to reach, she does use the Internet to reach out herself, posting on Twitter regularly: everything from random thoughts (“dont mis-treat robots, one day you or you’re children will regret it”) to updates about her life (“its 7 am and i just stayed up all night writing the best song i have ever written holy fuck. this is 100% what i live for”) and even thoughts about Twitter itself (my favorite: “i like twitter cuz u can just say things and lots of ppl will read it. shit shit shit shit cunt cunt cunt cunt hahaha”). “[Twitter] allows you to speak in a way in which you’re comfortable,” she says, alluding to her general hesitancy with interviews, when she worries that what she has to say might be misunderstood.

For example: the term “post-Internet,” which Claire once used in an interview to explain, as she says, “the very clear situation that obviously the Internet has changed the way people consume music,” how it provides access to music across all genres, encouraging a pastiche of influence. (Claire herself culls in uence from across the spectrum, citing Mariah Carey, Aphex Twin, Marilyn Manson and Timbaland as key figures.) “Post-Internet,” in an accidental and not entirely inappropriate instance of coining culture, has become a self-perpetuating meme, attributed to her music in a way she didn’t expect. “People are starting to refer to it as if it were a genre, which is not the way it was intended,” she says. “It’s not that I’m a post-Internet artist; it’s that the Internet exists now, and at one point it didn’t.” Fittingly, she turned to Twitter to renounce the term entirely, posting, “omg ‘post internet’ whatever i was running my mouth i don’t support the use of that term—not affiliated with it yoooooo.”

Of course the Internet has changed the music industry, and Claire’s career is representative of that, as she’s largely disseminated her music online and developed initial buzz via blog posts and reviews. (When Visions leaked, Claire even tweeted, “I support online piracy.”) The term “post-Internet” may have evolved beyond what she intended but perhaps necessarily so. Still, she prefers to keep her distance: “I’m just worried that it gives me an air of faux intellectualism.”

It’s now well past 1 a.m., and our conversation devolves from “interview” into “catching up.” Claire teaches me about K-pop and tells me about the time her dyslexic friend managed her books. We talk about how excited she is to visit parts of Europe she’s never been to before and about the next time we will get to see each other. I’ll be in Montreal for the debut of her “Oblivion” video, but unfortunately, she’ll still be on tour. We talk about her fear of becoming a tired musician, and how putting so much of herself into her music allows her to remain real in a sound that is heavily mechanical and synthesized.

“Translating personality into computerized music is a difficult thing to do,” she says. The best she can try for is to connect with the audience by getting them to dance, and as she says when considering the possibilities, “There are so many ways that you can push people with music.” //