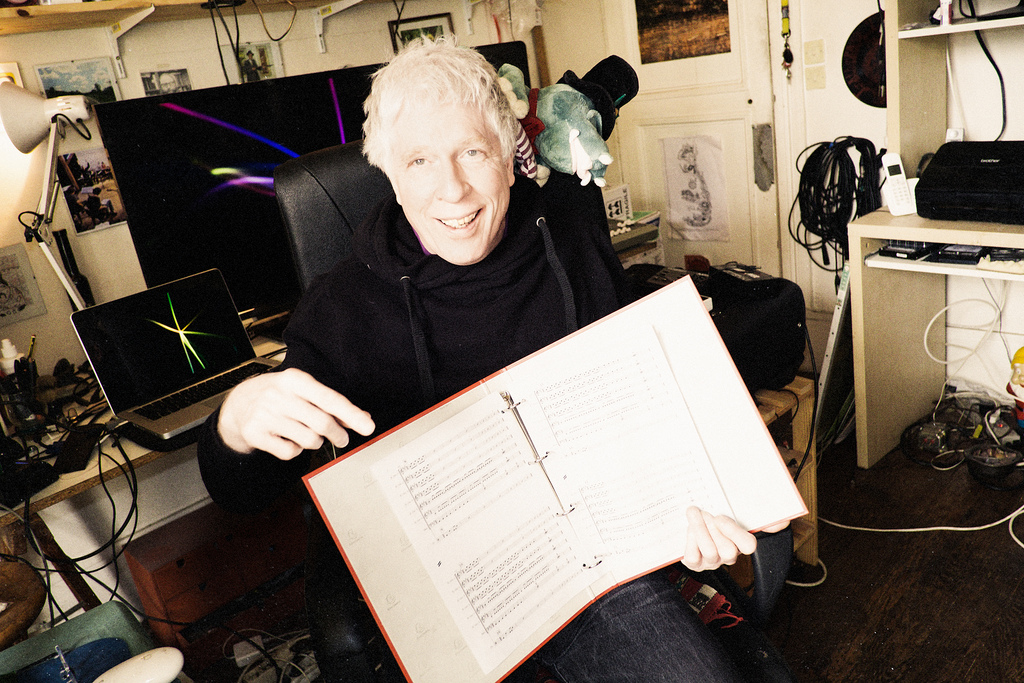

The downtown music icon explains

how he’s crossed paths

with everyone from Glenn Gould to Glenn Branca

Photos by Matthieu Lemaire-Courapied

When I was in the no-wave scene, that was a curse word—’composer’. People like Lydia Lunch and James Chance would beat me up after a concert, like, ‘Oh, you conservatory musicians, we don’t want to hear anything about you!’ So I had to prove myself.

I’m essentially a minimalist composer though. I studied with La Monte [Young] and worked with people like Tony Conrad, so I’m definitely coming from that background, although now I just don’t care. I’m a composer/performer, you know? In the same tradition as Terry Riley, who was the model for us all.

Kids today have a hard time getting their pieces played. The solution in my generation was we performed everything ourselves. Like with Peter Gordon—he just put an orchestra together, the Love of Life Orchestra. It had Philip Glass in it originally, Laurie Anderson, Arthur Russell, me. And it was just normal; we all lived in the same neighborhood, so we just traded our services.

That was one method. The other method was going the route of Morton Subotnick, which was collaborating with an engineer like Don Buchla. The reason the synthesizer was so exciting in the late ’60s was because you didn’t have to rely on musicians anymore. You could do the music yourself, in the same way things are now with programs like GarageBand.

Morton was the person who put me on the map. I took some electronic music courses with him at New York University, and then he graciously let me, this 16-year-old kid, use his studio on weekends. I’d go there and meet fantastic people like Ingram Marshall, Maryanne Amacher, and Serge Tcherepnin, the inventor of the Serge synthesizer. Forgive my French, but [Morton]’s the shit.

My father was a harpsichordist, so my first involvement with music was that—tuning harpsichords for people. I even tuned Glenn Gould’s harpsichord once. That was a trip man…He was playing a Brandenberg piece for the movie version of Slaughterhouse Five. They had the entire Philharmonic at RCA Studios, and of course, Glenn Gould’s harpsichord was a total piece of crap, because these pianists have such a heavy touch.

It takes 20 minutes to tune a harpsichord, but no one was there until between 8:50 and 9, when 100 people showed up. So the instrument was horribly out of tune, and the producers were tearing their hair out. They asked Glenn and he points at me and says, ‘Heh, heh, heh, ask him.’ I tuned it in 15 minutes, but I had to write a letter to the producers saying what a terrible instrument it is.

[Glenn] was everything you’d think he’d be—a totally eccentric man who came in with this piano seat his father built for him. It looked like a complete torture instrument, but it was the only seat he’d work with.

We were these crazies who brought tonality back into contemporary music when it was a dirty word for composers. So we didn’t get much of a chance to play uptown; we had the Kitchen, and a little bit later, Phil Niblock’s place.

When Garrett [List] started to program jazz at the Kitchen—artists like Don Cherry and Anthony Braxton—it caused quite a stir. People would say, ‘Those people already have a place to play; why are you bringing them here?’ But Garrett wanted to make a point that there’s no hierarchy between this music, that there shouldn’t be a pyramid where classical is on top, jazz is somewhere below that, and rock doesn’t even register.

In the meantime, there was this whole explosion at CBGB’s. It got to a point where half of the downtown art scene was going to CBGB’s, and the other half was in the bands. So when I got back to the Kitchen, I wanted to reflect that and book groups like DNA and Lydia [Lunch]. I would have done the Contortions there, but James Chance had just beat up the audience [at the Artists’ Space Festival], including Robert Christgau, the chief rock critic at The Village Voice. He was taking a cue from Iggy Pop; his music was a very primal thing.

James is as intense as he’s always been; he hasn’t lost a thing.

Within a downtown context, it was Philip Glass, Steve Reich, Laurie [Anderson], Peter Gordon, Arthur Russell—all these people were down there. Then the rock thing happened.

I knew Patti Smith from the St. Mark’s Poetry Project. And then all of a sudden, she was at CBGB’s playing with Television. I can’t even tell you what an inspiration she was for all of us. Rock in the mid-’70s had gotten so technical, but then you had all these groups coming up after that initial wave of Patti, Talking Heads, Richard Hell, and the Ramones, of course. I had my personal epiphany seeing them.

They had just put out their first album, and what I saw changed my life. At the time, Philip Glass was using a lot of jazz instrumentation, influenced by Richard Serra’s Process Art. Steve Reich had studied in Ghana, so Drumming was very influenced by that. And my own teacher La Monte had been studying with Pandit Pran Nath. So I thought, ‘I’ve gotta find my thing.’ When I went to that Ramones concert, I found it. They might be using two more chords than I was, but I found a similarity there, and the next day I got a Fender electric guitar.

It’s taken 30 years, but I’ve finally worked up to two chords. And I’m hoping that 10 years from now, I’ll be where the Ramones were—at three.

CBGB’s was very exotic…Objectively it was a dive, but a lot of exciting music happened there. When I first saw the Talking Heads, it seemed so much bigger than it really was, like it was an arena.

That was really the spirit of the times. You had groups like Mars, DNA, Teenage Jesus and the Jerks—people who had something to express, and they just went up there and did it. The question became how far can you push rock before it’s not rock anymore?

If you can play “Giant Steps” in any tempo, that’s your music degree right there.

At Max’s Kansas City and CBGB’s back then, they threw beer cans at you, with the beer in them. And that’s if they liked you. So you can imagine what would happen if they didn’t like you.

The first time we played Guitar Trio at Max’s, I thought we were going to get lynched. At both CB’s and Max’s, there was a lot of violence. It was scary. But anyway, we did G3 there, and people were coming up to the sound person saying, ‘Where are you hiding the singers?’ Which meant I’d succeeded in what I wanted to do.

After Drastic Classicism—around 1982—I was headlining CBGB’s. It took me about four years to get to that point, and by that time, I felt like I’d paid my dues.

I was a little nervous before this other G3 performance at Max’s. I was in a cab with one of the guitarists; I had a little Jack Daniel’s, and my friend had a pill, a Quaalude. God knows what they had in the dressing room…All I remember about the evening is jumping on these tables, going whoosh here, and whoosh there with the guitar. It was so much fun.

Then this guy named Jim Fouratt came up with a crazy idea—actually paying musicians. A group like Live Skull could play Danceteria and get $500. I remember playing CBGB’s once, and at the end of the night, the band leader handed me $5. I just laughed; it’s CB’s! What are you going to do?

So this whole rock ‘n’ roll thing happened in the ’80s—Guitar Trio, Drastic Classicism, and all this wonderful music with Lydia [Lunch], DNA, Sonic Youth, Swans and my good friend Glenn Branca. It was just fantastic, but then I moved to France, and all of a sudden, I was hearing these teenagers pouring their hearts out on computers—groups like Atari Teenage Riot, Aphex Twin, Scanner, and that whole drum ‘n’ bass thing with Ed Rush.

When I first heard rap back in ’84, I was blown away by it. I tried to replicate rap rhythms with my trumpet, but I wasn’t skilled enough back then to do it. But in ’93 I was, so my Neon record was the result of that.

I’m much less ‘flatulent’ in my current compositions now. That’s not my term; it’s something critics have used when referring to my horn playing.

By the year 2000, there’d be so much drum ‘n’ bass, and composers were falling in the trap of doing whatever software allowed them to. Programs were great when they first came out, but people weren’t being creative enough with them, and then they got boring. So that’s when I got back into writing guitar pieces again.

I saw Lydia [Lunch] play the other night, and she’s just doing great. She doesn’t pretend to be any other age than she is, and she still looks great on stage. She’s actually playing those original Teenage Jesus and the Jerks songs. She’d kill me if I told her this, but the guitar playing has actually gotten more refined. For me, as a tuner, it’s gorgeous.

We did A Crimson Grail a few years ago at Lincoln Center, and my daughter played in it. She’s into good music—a lot of heavy metal, more on the black side of things. Anyway, I took her to the East Village where her mother and father met, and I showed her where we used to score our heroin, on 8th Street between [Avenue] C and D. And it was all sushi shops! I was so embarrassed.

Brooklyn now feels the way New York did in the ’80s, minus the crack.

When I first moved to France, I’d come back down to St. Mark’s Place once a year and always say, ‘Why did I move? This is my tribe.’ But then I came back in the year 2000 and I thought, it’s over here. I have nothing against rich kids, but in the early ’80s, you’d have poor kids like Robert Longo and Cindy Sherman mixing it up with people whose parents had a little more money. It was good to have that mixture, but the rents are so high now that it’s crowding working class kids out. Except for in Brooklyn.

I got really inspired by metal about five years ago—bands like Sleep. When I heard Dopesmoker, I just screamed. It was incredibly inspiring to me. I was like, ‘Fuck man, that’s minimalism!’

The reason I got into trumpet playing is because I wanted to play like [Black Sabbath guitarist] Tony Iommi. The problem with the guitar is it has all of these frets, and I’m not really a string player; I’m a wind player, so I can’t figure out where to put my fingers. The Neon record was me trying to play like Tony Iommi, only over an electronica beat.

Playing trumpet is a bitch.

Context is everything.

One more anecdote, and then we have to stop. If any of your readers end up playing Paris, tell them they shouldn’t expect the kids to jump and down, because this is the country of Descartes. What we do here is we listen critically, but people don’t move. You just want to spit at them so they’ll do something.

Anyway, I went to see Sunn O))) play here and I just couldn’t believe it—all these club-hardened kids had ear-to-ear grins on their faces, listening to what essentially sounds like early minimalism to me. It could have been Tony Conrad playing up there on violin; instead it was these guitars and Marshall stacks, this sound that is felt rather than heard. So I had an ear-to-ear grin too, like, ‘Oh, they’re playing my music! The music of my tribe, only they’ve made it theirs!’

Rhys Chatham performs at The Kitchen in New York this Saturday. The previous story first ran in our quarterly iPad journal. Look out for a new issue and a complete relaunch of our app later this fall.